SSO-backed MCP authentication: A practical guide for enterprise engineering teams

TL;DR

- Enterprise SSO establishes and enforces user identity, while MCP relies on that identity to authorize scoped access to tools.

- Scalekit sits between SSO and MCP, consuming authenticated identity and translating it into explicit authorization for MCP tools and servers.

- MCP clients, such as IDE extensions or internal tools, request capabilities using scopes; MCP servers enforce those scopes at runtime; neither component contains identity or role logic.

- Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) and Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD) provide flexible ways to onboard MCP clients without static OAuth configuration, each suited to different operational needs.

- Together, this model enables a stateless, auditable, enterprise-ready MCP deployment that fits cleanly into existing identity and security architectures.

When an MCP prototype meets the reality of enterprise identity

A platform team deploys an MCP server that enables developers to manage internal Jira tickets directly from VS Code. The workflow feels natural: no context switching, no browser tabs, just structured tool calls from the IDE. A small group of engineers adopts it quickly, and the feedback is positive. From a functional standpoint, the system appears ready to scale beyond a pilot.

The rollout slows when identity and security come into play. The company already runs on enterprise SSO backed by Okta, with MFA, device posture checks, and conditional access policies enforced centrally. Security teams expect every access path, web apps, internal services, IDEs, and automation to authenticate through the same identity provider and produce auditable events. Static API keys, long-lived tokens, or MCP-specific login flows break those expectations, even if they work in local demos. The open question becomes whether MCP can fit into this environment without introducing a parallel identity surface or weakening existing controls.

This guide explains how to bridge that gap in practice. Through a concrete VS Code–driven MCP integration with internal systems, it demonstrates that enterprise SSO remains the identity provider, that scoped credentials are issued for MCP servers, and that existing security policies continue to apply without modification. By the end, you’ll understand how to wire MCP authentication and authorization into an enterprise SSO setup using Scalekit in a production-ready, auditable way.

The real question enterprises ask about MCP and SSO

Once a prototype exists, enterprise teams don’t question whether MCP requires authentication. The real question is how MCP integrates with the identity system that is already deployed, audited, and enforced across the organization. In the VS Code and Jira example, developers already authenticate through Okta or a similar IdP, with identities, group memberships, and access constraints defined long before MCP enters the picture.

Enterprise SSO solves a specific problem: establishing a user's identity and verifying whether they are authorized to authenticate under current policies, such as MFA, device posture, and conditional access. MCP, by contrast, introduces a different concern. It needs to determine which tools a verified user can invoke, under which organizational context, and at what privilege level. Treating these as the same problem leads to brittle designs, usually involving long-lived tokens or custom login flows that security teams reject.

The practical requirement is separation without duplication. Identity should continue to come from the IdP, precisely as it does for other internal systems. MCP should consume that identity and apply it narrowly to tool execution. This distinction enables the VS Code workflow to feel seamless to developers while still fitting cleanly into an enterprise security model.

The core components that make SSO-backed MCP work

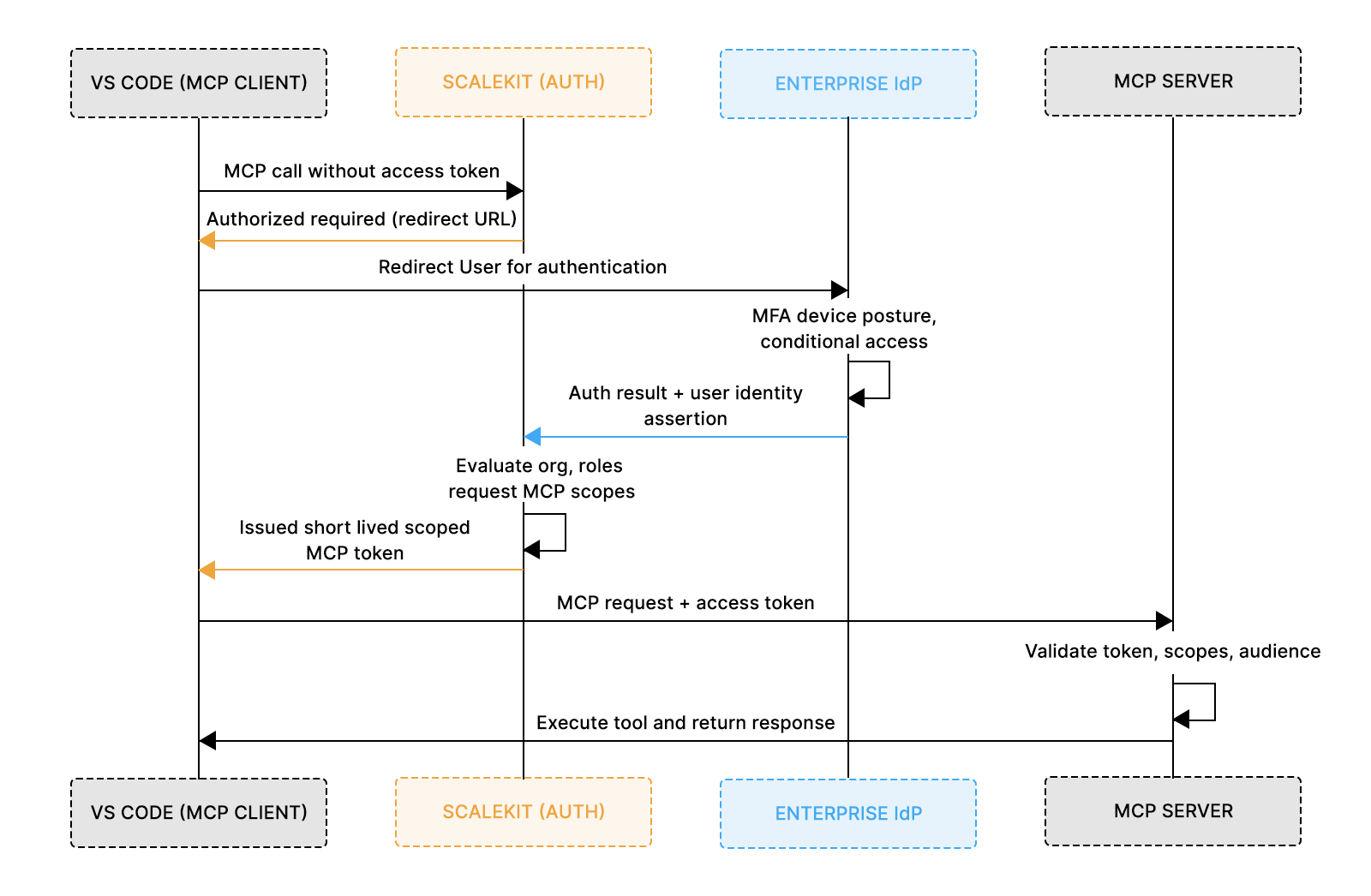

In the VS Code and Jira scenario, four distinct components participate in every authenticated MCP request: the MCP client, the enterprise identity provider, the authorization layer, and the MCP server. Each has a narrow responsibility, and keeping those boundaries clean is what makes the system production-ready. Collapsing these roles, especially identity and authorization, is where most early MCP integrations break down.

The MCP client, typically an IDE extension such as a VS Code plugin implementing the MCP client protocol, initiates MCP requests on behalf of a user but does not authenticate the user itself. Enterprise SSO systems like Okta or Azure AD remain the system of record for identity, applying MFA, device posture checks, and conditional access before asserting the user’s identity. Scalekit sits between these layers as an OAuth authorization server, federating with the IdP to consume authenticated identity context and issuing short-lived, scoped access tokens intended specifically for MCP servers.

The MCP server stays intentionally simple. It validates incoming tokens, enforces scope-to-method mappings, and executes tools without managing user sessions or talking directly to the IdP. In practice, this allows the Jira MCP server to answer authorization questions, such as whether a user can modify tickets for a given organization, without embedding SSO logic or duplicating enterprise policy, keeping the server stateless and secure.

With these responsibilities defined, the next step is wiring this architecture into a real system. The following section explains how an existing enterprise SSO setup is integrated with MCP via Scalekit, then traces a single authenticated request through the flow shown above.

This shift is already playing out in real MCP deployments. As teams move beyond prototypes, enterprise requirements like OAuth, SSO integration, and auditability become table stakes rather than nice-to-haves. Recent work shared by early MCP vendors highlights this exact transition: MCP functionality is straightforward to demo locally, but adoption inside larger organizations hinges on clean integration with existing identity systems and compliance workflows. This is where SSO-backed authorization stops being optional and becomes foundational.

Wiring an existing enterprise SSO into MCP using Scalekit

This section assumes you already have an enterprise IdP such as Okta, Azure AD, or Google Workspace in place. The goal here is not to change how users authenticate, but to integrate the existing SSO setup with MCP in a way that preserves enterprise controls while enabling scoped access to tools. Scalekit acts as the authorization layer that bridges these two worlds.

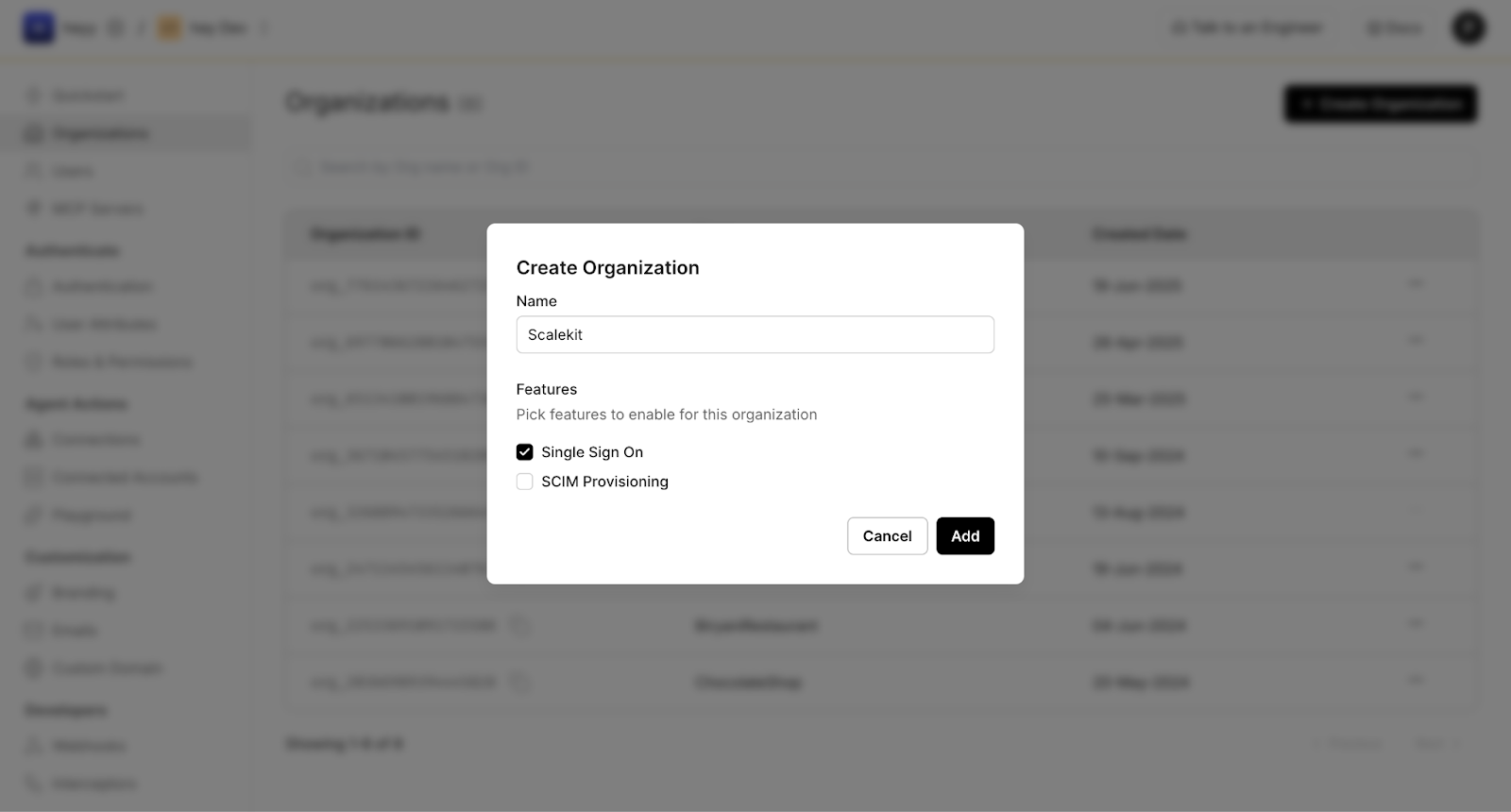

Step 1: Connect your enterprise identity provider to Scalekit

Every SSO-backed MCP setup starts by establishing an organization boundary in Scalekit. This represents the enterprise tenant whose identity system will be used to authenticate users and derive authorization context. At this stage, you enable SSO for the organization; no users, passwords, or MFA rules are created or duplicated. Scalekit will rely entirely on your existing IdP for authentication.

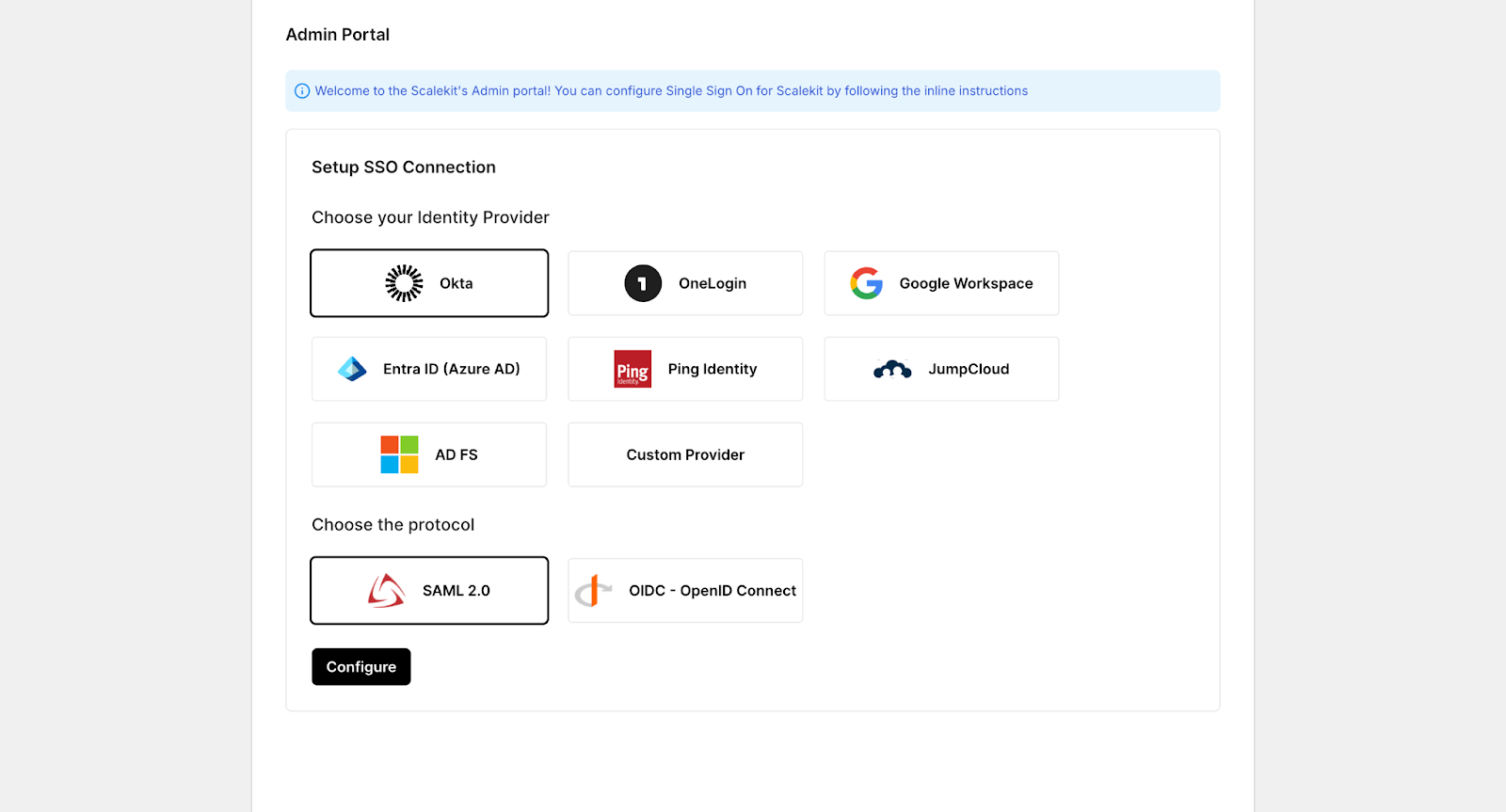

Once the organization exists, the next step is to federate your enterprise IdP. Scalekit supports common providers such as Okta, Entra ID (Azure AD), Google Workspace, Ping, and JumpCloud, using either SAML 2.0 or OIDC. The choice of provider or protocol does not change MCP behavior; it only affects how identity assertions are exchanged. In all cases, Scalekit acts as a service provider that consumes identity claims from your IdP.

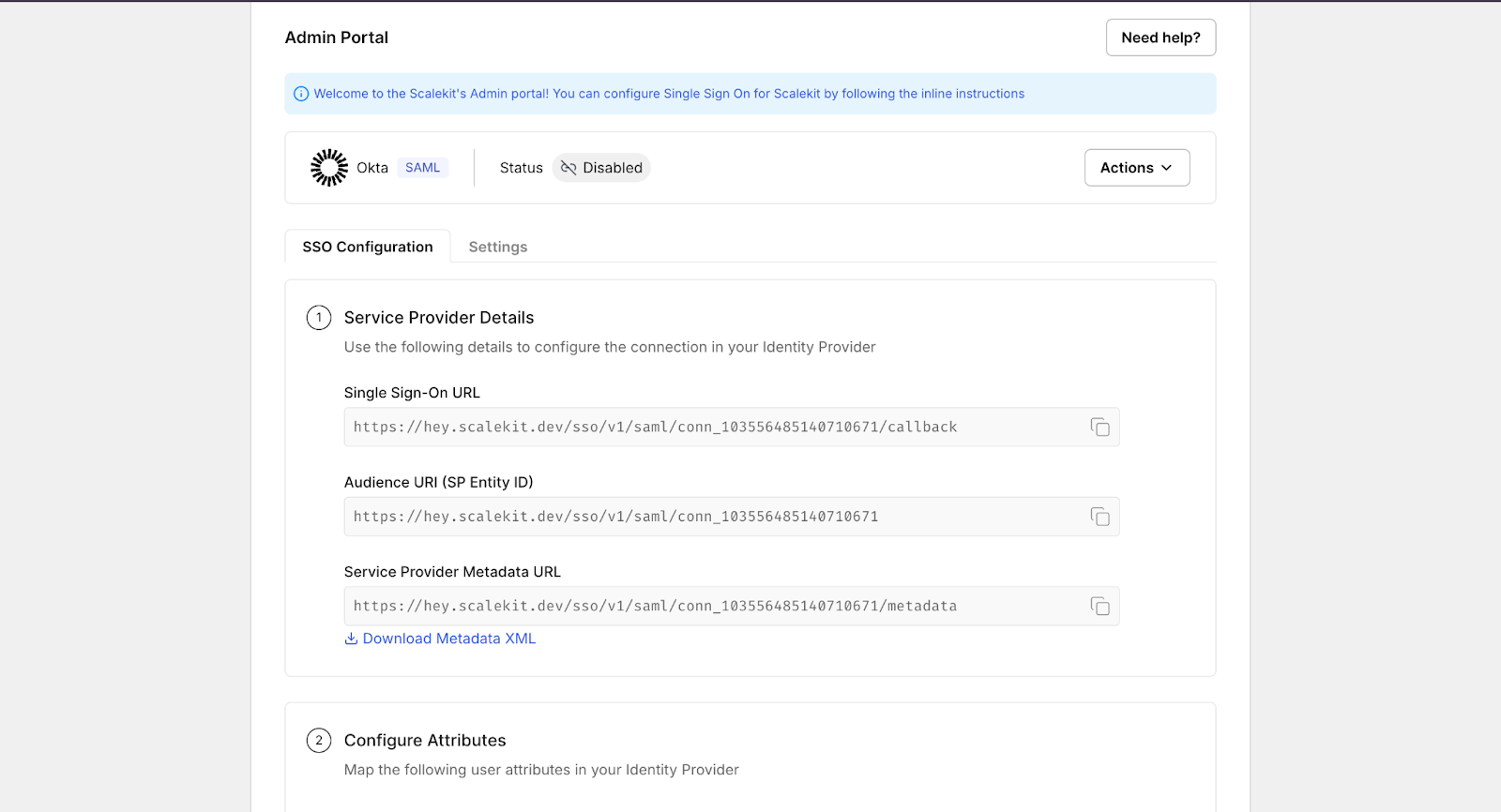

Scalekit provides service provider details such as the SSO callback URL, audience (entity ID), and metadata endpoint, which you use to create an enterprise application in your IdP. In Okta, Azure AD, or Google Workspace, this follows the same pattern: create a new enterprise app, paste the Scalekit-provided values, map required user attributes (for example, email and group membership), and assign users or groups. No MCP-specific concepts are introduced at the IdP level.

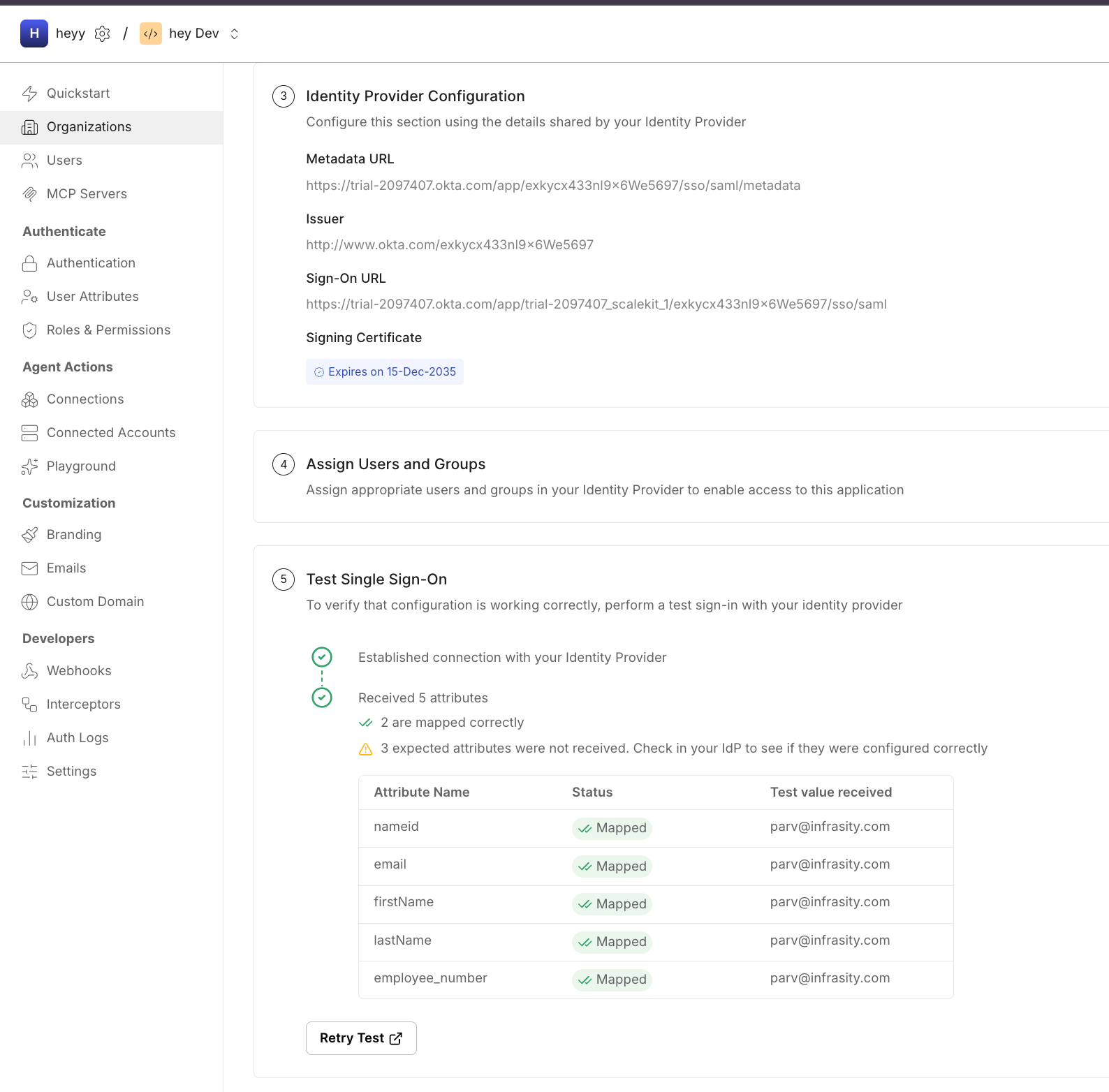

Finally, you complete the trust relationship by uploading the IdP’s metadata back into Scalekit and testing the connection. Once enabled, users assigned in the IdP can authenticate via enterprise SSO, and Scalekit can reliably consume identity assertions to drive downstream MCP authorization.

At the end of this step, enterprise SSO remains the system of record for identity, while Scalekit is positioned to issue scoped credentials for MCP based on that identity. No MCP servers are involved yet, and no authorization logic has been applied; those come next.

Step 2: Register the MCP client (IDE or Internal tool)

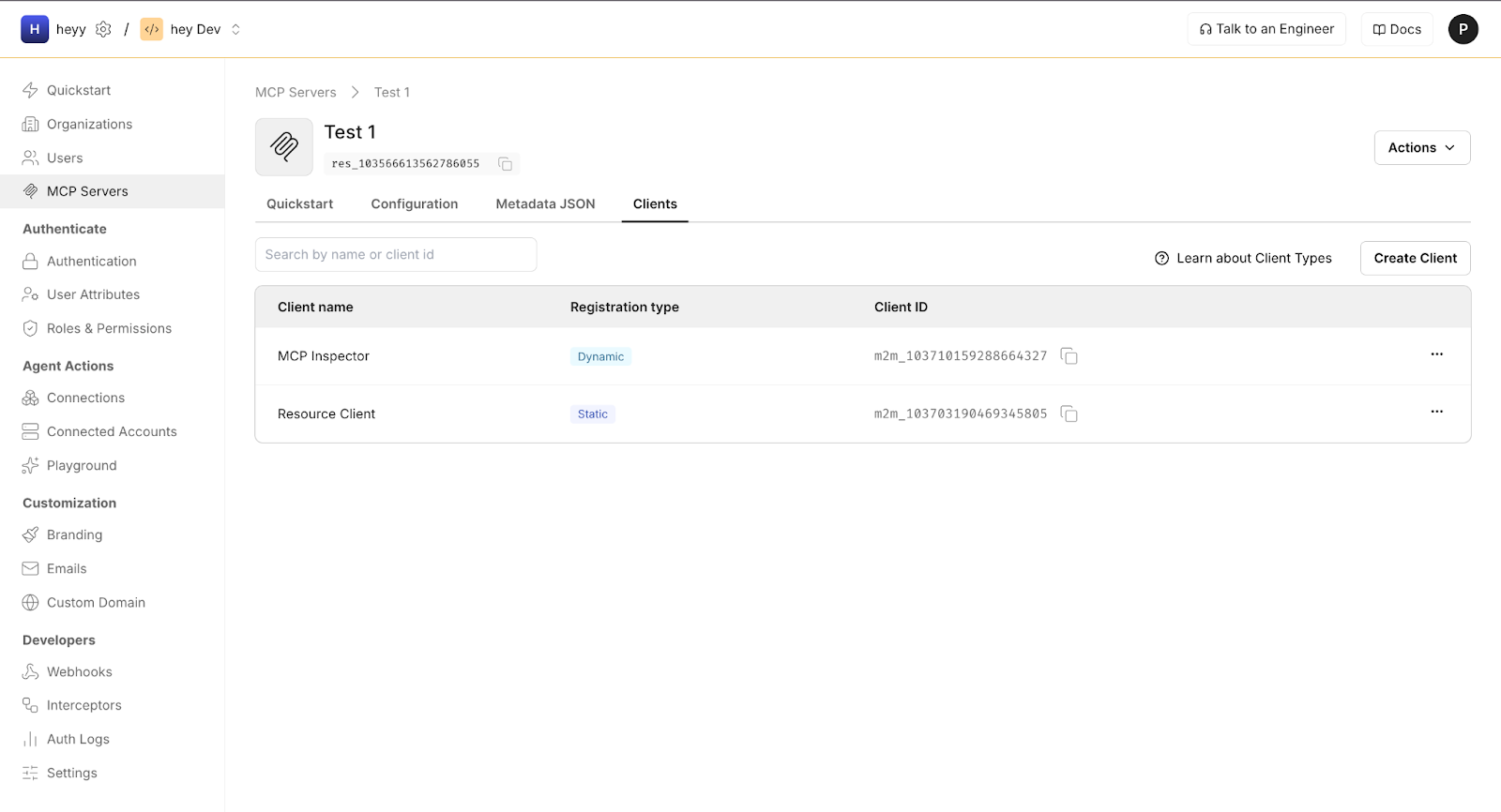

With enterprise SSO in place, the next step is registering the MCP client that will request access on behalf of users. In this example, the client is MCP Inspector, but the same model applies to IDE extensions and internal tools as well. MCP clients are not pre-registered OAuth apps; Scalekit is designed to onboard them dynamically.

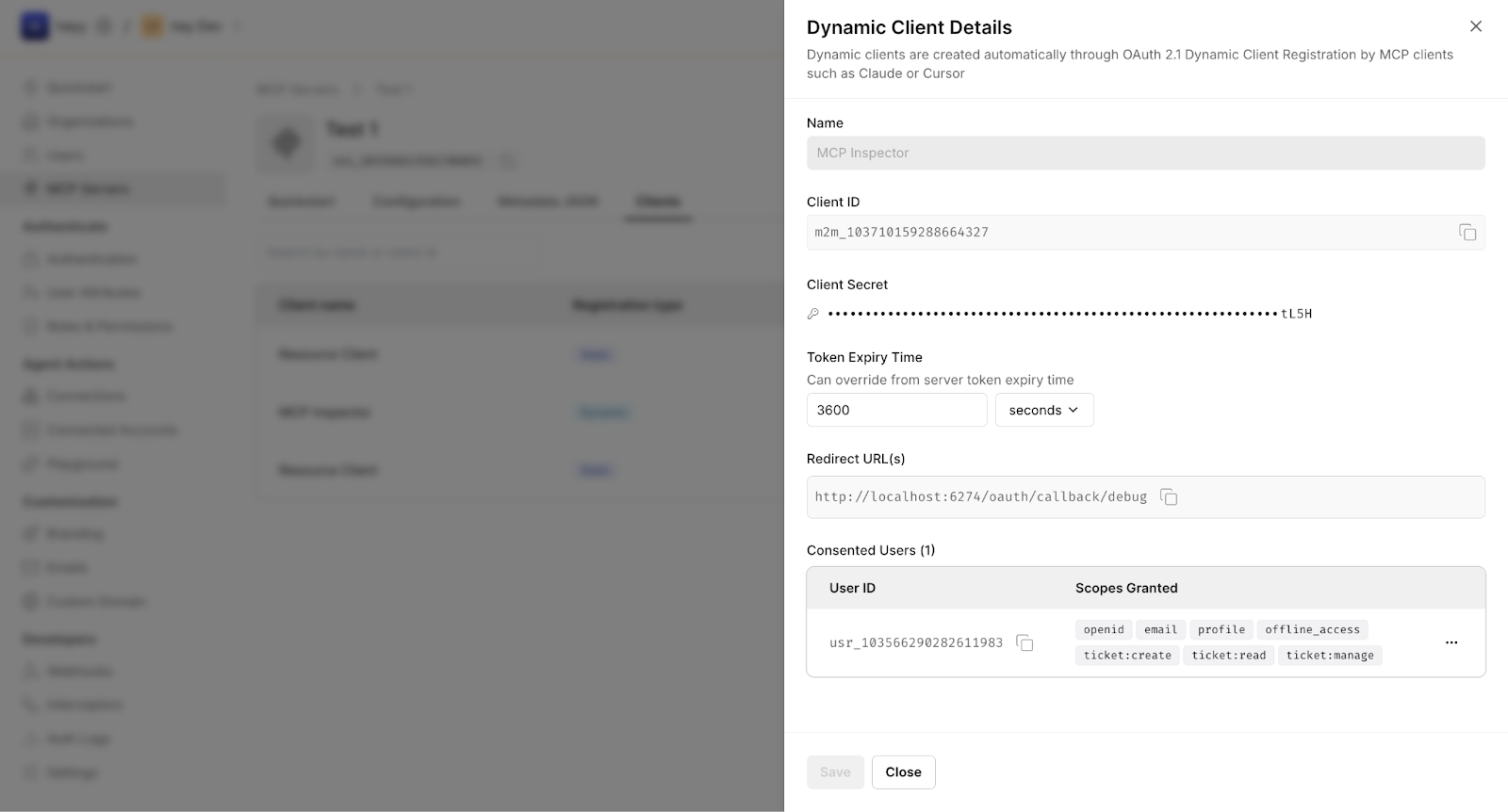

In this flow, the client is registered using OAuth 2.1 Dynamic Client Registration (DCR). When the client initiates its first authorization request, Scalekit automatically creates a client record scoped to the target MCP server. This avoids manual provisioning while keeping each client visible and auditable.

Each registered client is bound to a generated client ID, the redirect URL used by the tool (for example, a localhost callback), the MCP server audience, and the scopes granted after user consent.

Scalekit also supports Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD) for MCP clients. CIMD allows long-lived or widely distributed tools to publish stable client metadata that Scalekit can fetch and validate, while preserving the same authorization and enforcement model. DCR works well for ephemeral tools; CIMD is better suited for production-grade clients.

At the end of this step, the MCP client, whether registered dynamically or via CIMD, is authorized to request scoped access on behalf of authenticated users. The next step defines what those scopes mean and how they map to enterprise policy.

Step 3: Define MCP scopes and authorization rules

This step defines the set of actions MCP clients can request by introducing MCP-specific scopes. In Scalekit, scopes map directly to MCP methods, such as reading or modifying Jira tickets, and can include organizational context to enforce clear boundaries. Scopes are intentionally fine-grained and can include organizational context to enforce clear boundaries.

Authorization rules then map enterprise identity attributes to these scopes. For example, users in a Jira-admins group can be granted tickets.manage:org-123, while users in a read-only group receive tickets.read. The identity provider remains unaware of MCP concepts; it continues to assert identity and group membership, while Scalekit translates these into MCP-specific permissions at authorization time.

At runtime, the resulting scopes are embedded into the access token issued by Scalekit. MCP servers rely exclusively on these scopes to authorize method execution, keeping authorization explicit, auditable, and decoupled from identity systems.

How roles and permissions are applied in MCP

Roles and permissions are defined centrally in Scalekit, not inside MCP clients or MCP servers. In Scalekit, enterprise roles or group memberships are mapped to MCP scopes through authorization rules. These scopes become the single representation of permissions across the system.

MCP clients use these permissions by requesting scopes during authorization. The client does not decide what it is allowed to do; it only declares which capabilities it needs. Scalekit evaluates the request against enterprise identity and policy before issuing a token.

MCP servers enforce permissions by validating scopes at runtime. Each MCP method declares the scopes it requires, and requests missing those scopes are rejected. No role lookup or IdP interaction happens inside MCP; authorization is driven entirely by the scopes issued by Scalekit.

Mapping MCP methods to scopes and enterprise policies

In MCP, scope design defines the contract between what a client may request and what a server is willing to execute. Each MCP method corresponds to one or more scopes, making authorization explicit and enforceable at the method boundary. In the Jira example, reading, creating, and modifying tickets are treated as separate capabilities, even though they target the same underlying system.

Scalekit issues scopes that are both capability-specific and context-aware. For example, tickets.read grants read-only access, while tickets.manage:org-123 restricts write access to a specific organizational boundary. These scopes are derived during authorization using enterprise identity signals such as group membership or roles, without requiring the identity provider to understand MCP semantics.

Enforcement happens entirely at the MCP server. Each exposed method declares the scopes it requires, and requests missing those scopes are rejected before any logic executes. This keeps authorization decisions close to the code path that performs the action, allowing MCP servers to remain stateless, predictable, and aligned with enterprise security boundaries.

Step 4: Configure the MCP server to trust Scalekit

The final wiring step is configuring the MCP server to trust Scalekit as its authorization authority. This is a one-time setup in which the server validates Scalekit-issued access tokens using the published signing keys. The MCP server does not integrate with the enterprise IdP directly and does not perform token introspection or session management.

From this point on, any request carrying a valid Scalekit-issued token is treated as an authoritative statement of the caller’s allowed actions. The MCP server validates the token, checks required scopes, and executes the requested method. All enforcement happens locally, keeping the server stateless, predictable, and easy to operate.

Bridging back to the request flow

With this wiring complete, the flow shown earlier becomes concrete. The IdP authenticates the user, Scalekit issues scoped MCP tokens based on enterprise policy, and MCP servers validate and enforce those tokens without embedding identity logic. The next section follows a single MCP request through this setup, step by step, to show how these pieces behave at runtime.

A step-by-step walkthrough of an authenticated MCP request

This section follows a single MCP request end-to-end, using MCP Inspector as the concrete client. MCP Inspector is used here because it makes the flow visible and inspectable; the same sequence applies when MCP is embedded in an IDE such as VS Code, Cursor, or other internal developer tools. In those environments, the IDE extension serves as the MCP client and handles the flow automatically.

The goal here is to make the authentication and authorization wiring discussed earlier observable at runtime, without revisiting setup or identity fundamentals.

Step 1: The MCP client initiates an authenticated request

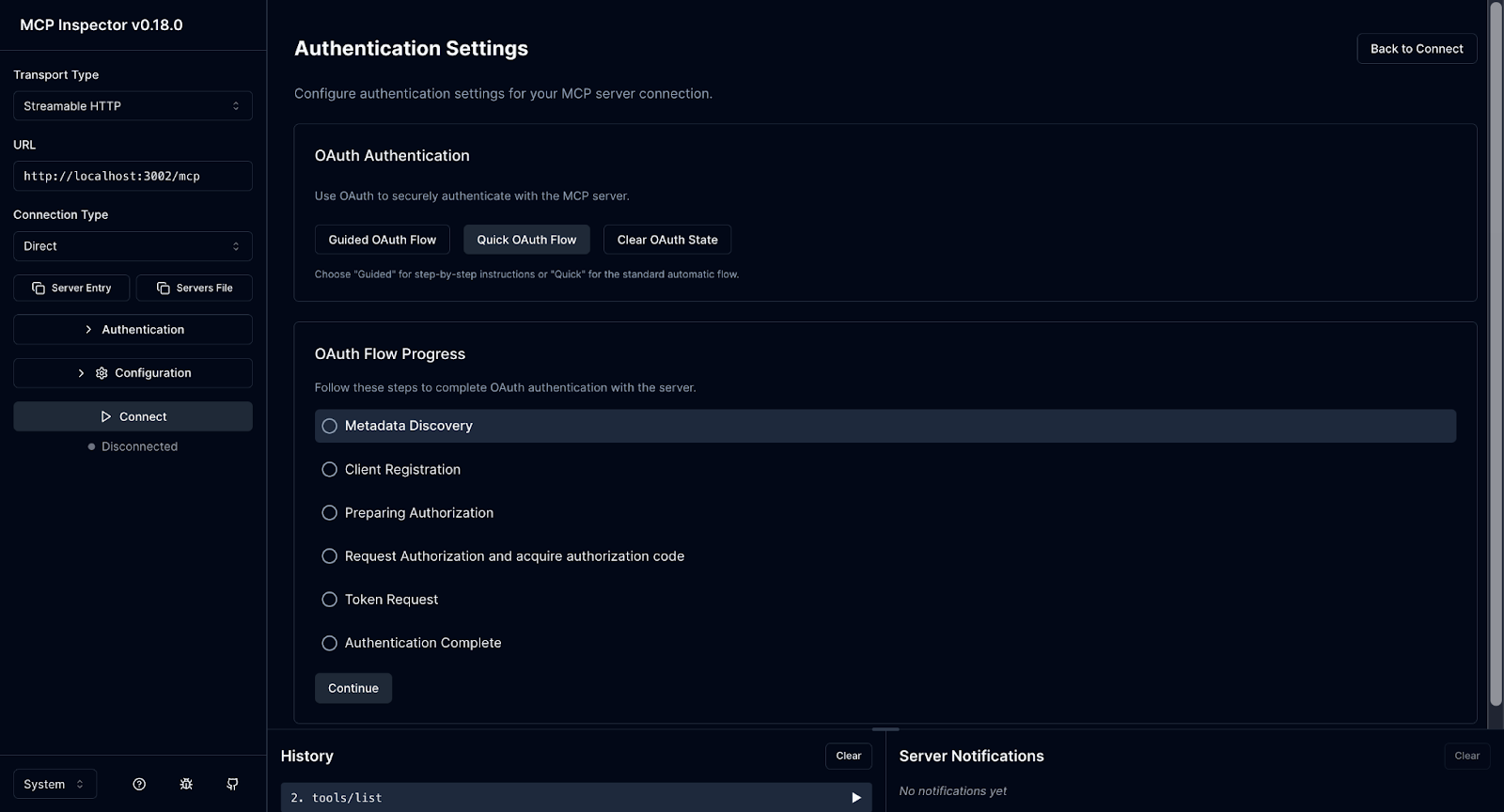

The flow begins when a developer triggers a tool call from an MCP client such as MCP Inspector. At this point, the client does not yet have a valid access token. Instead of attempting to call the MCP server anonymously, the client detects this condition and initiates an OAuth authorization flow against Scalekit.

This distinction is essential. The MCP client is not authenticating the user itself. It is requesting permission to invoke MCP methods on a specific server, with a defined set of scopes and an explicit audience.

Step 2: The user authorizes MCP access via enterprise SSO

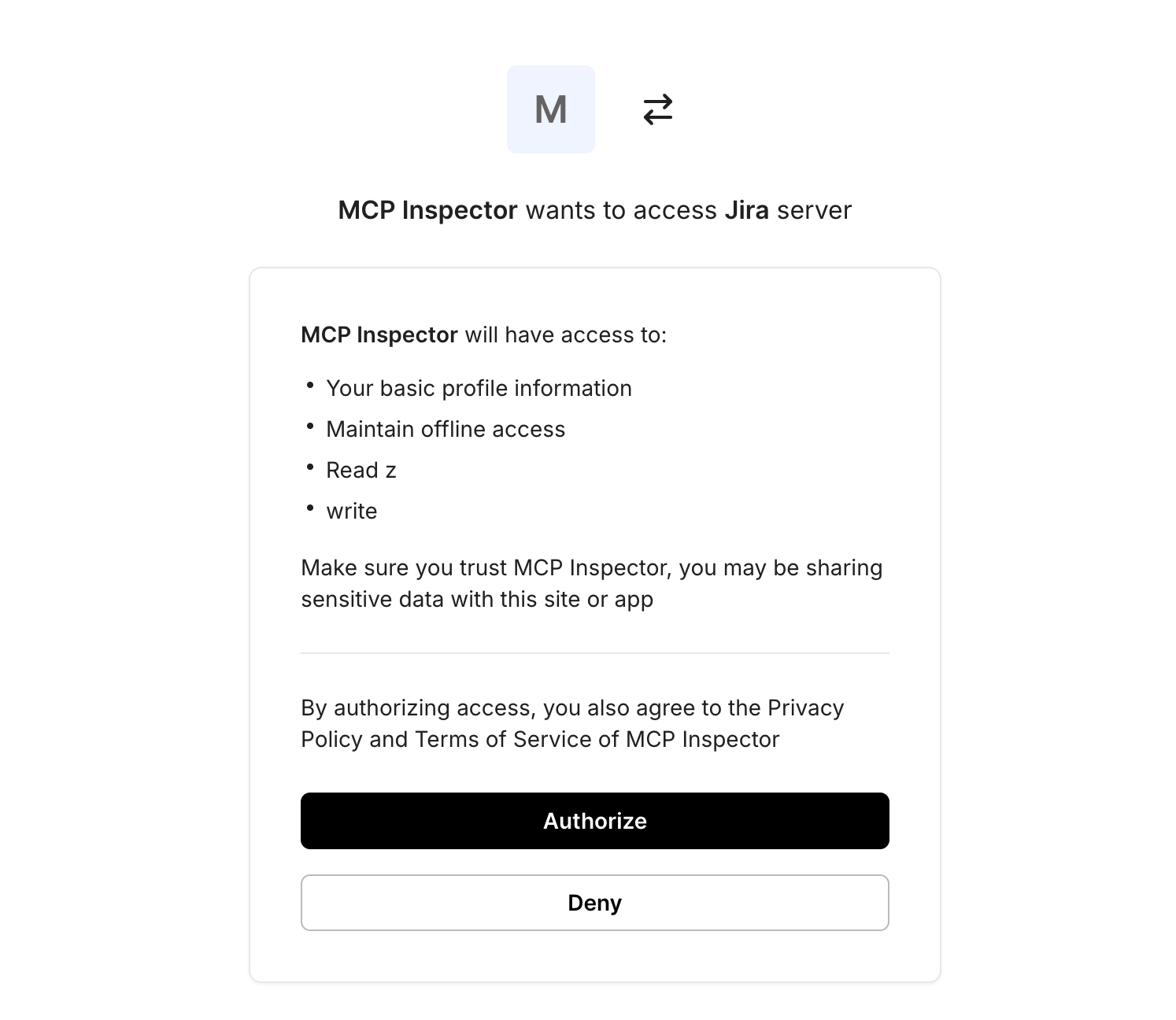

Once the authorization flow starts, the user is redirected through the enterprise SSO system via Scalekit. Authentication happens under existing enterprise policies. MFA, device posture checks, and conditional access are enforced by the identity provider exactly as they are for other internal applications.

After authentication completes, Scalekit presents a consent screen that describes what the MCP client is requesting access to, expressed as scopes. This is where authorization becomes explicit and inspectable.

Step 3: The MCP server validates the token and executes the tool

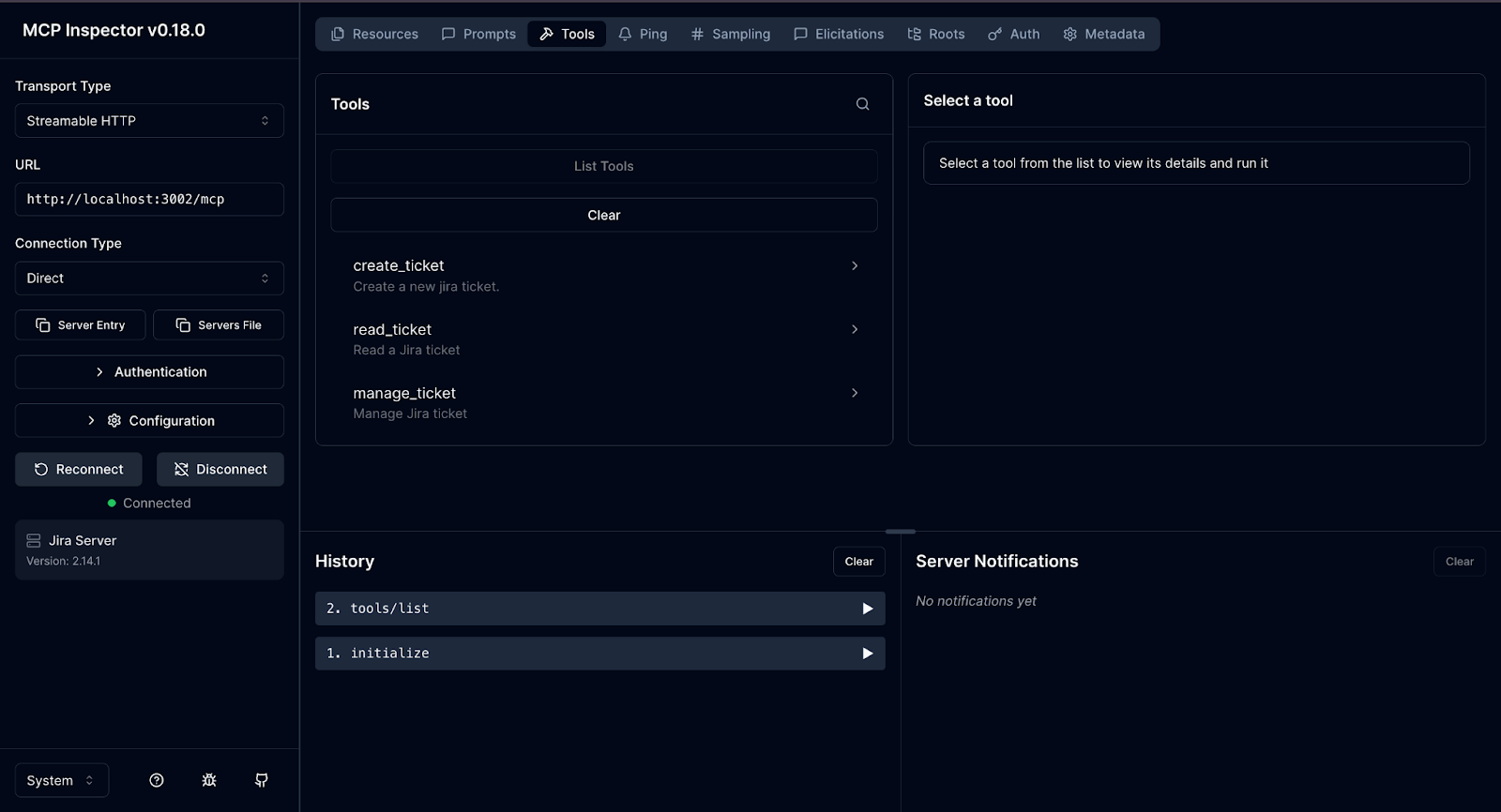

After authorization, the MCP client retries the original request with the issued access token attached. The MCP server validates the token locally by checking the issuer, audience, expiration, and scopes. If the required scopes are present, the server executes the requested method.

In this example, the tool invocation succeeds because the token includes the appropriate permissions. No redirects occur, no identity lookups are performed, and no session state is stored. The MCP server remains stateless and focused solely on execution.

A note on IDE-based MCP clients

While MCP Inspector is used here for clarity, the same flow applies when MCP is embedded directly inside an IDE. In those cases, the IDE extension acts as the MCP client: it initiates the authorization flow when needed, handles browser redirects, and automatically attaches the resulting access token to tool calls.

From the MCP server’s perspective, there is no difference between requests originating from MCP Inspector and those coming from an IDE. In both cases, authorization is expressed entirely through the scoped access token issued by Scalekit.

What an MCP access token contains and how servers validate it

An MCP access token is the sole artifact an MCP server relies on to make authorization decisions. It is not an identity token, a browser session, or a proxy for an IdP login. Authentication has already happened upstream through enterprise SSO. The access token represents the result of that authentication expressed as explicit, time-bound permissions that an MCP server can verify locally.

Why MCP servers should never consume IdP tokens directly

IdP-issued tokens are designed to prove identity to first-party applications, not to authorize fine-grained execution of tools. They often have broad audiences, long lifetimes, and semantics that change across providers. Passing them directly to MCP servers couples tool execution to IdP behavior and forces MCP servers to understand enterprise identity policies they should not own. Instead, MCP servers trust a dedicated authorization authority, Scalekit, to translate enterprise identity into MCP-specific permissions.

Minimal token structure required for MCP

An MCP access token should contain only the fields required for deterministic authorization:

- iss (issuer)

Identifies Scalekit as the authorization authority. MCP servers must reject tokens from any other issuer.

- Sub (subject)

A stable identifier for the authenticated user. This value is used for audit correlation, not for permission inference.

- Aud (audience)

Identifies the target MCP server or server group. Tokens must not be valid across unrelated MCP services.

- exp (expiration)

Enforces a short validity window. MCP tokens are intentionally short-lived to reduce blast radius and avoid complex revocation paths.

- Scope

An explicit list of MCP capabilities, such as tickets.read or tickets.manage:org-123. All authorization decisions flow from this field.

- organization or tenant context (optional but common)

Encodes the boundary within which scopes apply, allowing MCP servers to enforce isolation without additional lookups.

Anything beyond this typically increases coupling without improving security or correctness.

How MCP servers validate access tokens

Token validation in an MCP server is a strict, local gate that runs before any tool logic executes. The process is synchronous and side-effect free:

- Verify the token signature using Scalekit’s published signing keys.

- Validate the issuer matches the expected authorization authority.

- Confirm the audience matches the receiving MCP server.

- Reject expired tokens without attempting to refresh or introspect them.

- Enforce method-level scopes explicitly for the requested MCP method.

If any check fails, the request is rejected immediately. MCP servers do not redirect users, call back to Scalekit, or contact the IdP during execution.

Why this design holds up in production

This model keeps MCP servers stateless, horizontally scalable, and isolated from identity system complexity. Authorization decisions are explicit, inspectable, and auditable. In the Jira example, a request to modify tickets succeeds solely because the token contains the tickets.manage:org-123 scope, not because the client is trusted or because the user recently authenticated. Security teams can reason about access by inspecting scopes, and platform teams can evolve MCP servers without changing IdP configuration or client behavior.

Operational considerations for running SSO-backed MCP in production

Once MCP authentication works end-to-end, most issues arise not from correctness but from operability. IDEs behave differently from browsers, tokens expire at inconvenient times, and security teams expect clean offboarding and auditability. Treating these as first-class concerns is what separates a pilot deployment from a system that can be rolled out across an organization.

Redirect handling for IDEs and non-browser clients

MCP clients are often IDE extensions, CLIs, or background agents rather than traditional web apps. These clients still need to complete OAuth redirects, but they cannot rely on hosted callback URLs. In practice, this means supporting localhost redirect URIs or device-style flows that can safely hand control back to the client. Scalekit serves as the OAuth entry point, enabling enterprise SSO policies while supporting non-browser environments. The key invariant is that redirect handling remains a client concern, while authentication policy remains centralized.

Token lifetime, refresh, and re-authentication

MCP access tokens should be short-lived by default. Short lifetimes reduce the blast radius and simplify revocation, but they raise questions about refresh behavior. For IDE-driven workflows, it is often safer to re-authenticate through SSO than to rely on long-lived refresh tokens, especially in environments with strong device or network policies. Scalekit allows teams to tune token lifetimes centrally, keeping MCP servers stateless and eliminating the need for them to manage refresh logic.

Revocation, offboarding, and policy changes

Enterprise systems must respond quickly to identity changes. When a user is removed from a group, loses device trust, or leaves the organization, MCP access should be revoked automatically without manual cleanup. Because authentication and authorization are derived from SSO and evaluated at token issuance, revocation occurs automatically on the next authorization attempt. Short token lifetimes ensure that stale permissions expire quickly, while centralized policy evaluation prevents changes from propagating across MCP servers.

Auditability and request correlation

Every MCP request should be traceable back to a user, a client, and a specific action. This requires consistent identifiers across tokens, logs, and MCP server execution. Tokens issued by Scalekit carry stable subject identifiers and scopes that MCP servers can log alongside method invocations. In the Jira scenario, this enables answering questions such as which user modified which ticket, from which client, and under which organizational context, without correlating data across multiple identity systems.

Conclusion

MCP is not an identity system and does not participate in user authentication. Enterprise SSO systems, such as Okta or Azure AD, remain fully responsible for establishing user identity and enforcing authentication policies, including MFA, device posture, and conditional access. MCP assumes that identity has already been verified and focuses exclusively on authorization at the tool and method level.

In this guide, we showed how that separation works in practice. Using Scalekit as the authorization layer, authenticated enterprise identity is translated into scoped MCP access tokens that MCP servers can validate locally. MCP clients request explicit capabilities, MCP servers enforce them deterministically, and no identity logic is embedded into MCP runtime components.

To go deeper, start with Enterprise-Ready MCP (B1) for architectural context, then explore the MCP Authorization specification and SEP-990 for protocol details. For a broader perspective on cross-app authorization and trust boundaries in agent-driven systems, see the Cross-app access (XAA) post. Together, these resources show how MCP can be deployed in enterprise environments without changing how identity is managed today.

FAQs

1. Is MCP an alternative to enterprise SSO?

No, MCP does not authenticate users or replace enterprise SSO. SSO systems establish identity; MCP operates only after authentication, using that identity to authorize tool execution.

2. Where does Scalekit fit in the MCP authentication flow?

Scalekit acts as the authorization authority for MCP. It federates with the enterprise IdP to consume authenticated identities, evaluate policies, and issue scoped access tokens that MCP servers can validate.

3. Where are MCP roles and permissions defined?

Roles and permissions in Scalekit are defined as scopes and authorization rules. MCP clients request scopes, and MCP servers enforce them. No role logic exists inside MCP clients or servers.

4. When should I use DCR versus CIMD for MCP clients?

Use DCR for ephemeral or exploratory clients such as MCP Inspector or experimental agents. Use CIMD for long-lived or widely distributed MCP clients that require a stable identity and predictable configuration.

5. Do MCP servers ever interact with the IdP or store sessions?

No, MCP servers validate tokens issued by Scalekit using signing keys and scopes. They never redirect users, query the IdP, or store session state, keeping execution stateless and scalable.