CIMD vs DCR: How to Choose the Right Model for Your MCP Deployment

TL;DR

- MCP has two valid identity models, DCR and CIMD, because modern agent ecosystems contain both predictable and fast-changing clients.

- DCR works best when the client set is curated, stable, and governed, making it well-suited for enterprise systems, long-lived services, and vetted partner integrations.

- CIMD is a better fit for dynamic, user-local, or short-lived MCP clients, including IDE extensions, CI runners, exploratory agents, and open developer tooling.

- Most real deployments succeed only when they support both models simultaneously, since no single approach can match the diversity of clients interacting with a modern MCP server.

- Scalekit supports both DCR and CIMD natively, enabling teams to onboard thousands of diverse MCP clients at scale without rewriting authentication logic or maintaining brittle registration workflows.

Why MCP client onboarding break in real deployments

Client onboarding becomes unpredictable the moment an enterprise deploys MCP in production. A dev team might begin by enabling MCP for expected use cases such as IDE plugins, internal developer tools, and routine automation agents. These clients behave consistently at first. But as soon as developers experiment locally, CI jobs spin up short-lived workers, or contractors connect using inconsistent setups, the MCP server starts receiving metadata patterns no one accounted for. Logs fill with unfamiliar client identifiers, and the team loses clarity on which clients were intentionally onboarded and which were onboarded by accident.

Security and infrastructure reviews reveal how quickly onboarding assumptions break down. A registration endpoint that once served a handful of internal applications now handles requests from remote networks, ephemeral agents, and tools whose capabilities change weekly. The server accumulates outdated registrations, duplicated metadata, and conflicting definitions between teams. It raises concerns because the identity records inside the server no longer match the reality of who is using the system. What looked like a simple onboarding flow becomes a fragmented identity landscape with no reliable source of truth.

This blog explains why this happens and how to fix it using the right onboarding model for MCP ecosystems. We outline how Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) works, why traditional assumptions fail in distributed engineering environments, and how Client-Initiated Metadata Documents (CIMD) offer a stateless alternative that scales more cleanly. We examine real scenarios, pain points, and decision frameworks used by engineering teams. Throughout the blog, we will also see how Scalekit makes both models work together, so teams don’t have to “choose a side”, so organizations avoid infrastructure redesign whenever a new client appears. By the end, you’ll have a practical way to decide when to use DCR, when CIMD is the better fit, and why many teams adopt both.

Why traditional client registration fails in MCP ecosystems

MCP onboarding breaks down because MCP clients behave nothing like traditional OAuth or API consumers. In our earlier story, the dev team expected to onboard a few predictable tools: an internal code-review bot, a stable partner integration, or a versioned CLI utility with a slow release cycle. Instead, they faced a fast-moving ecosystem: IDE extensions updating weekly, AI agents rewriting their own capabilities, short-lived CI workers running for minutes at a time, and partner systems producing inconsistent metadata. This shift created a client landscape that changed faster than any server-managed registration table could reliably track.

The MCP registration endpoint becomes a bottleneck once these clients scale. Every tool that posts metadata to /register forces the server to store, validate, and later clean up that metadata. Over time, the registry fills with stale definitions, duplicate entries, abandoned clients, and mismatched versions. The server’s stored state drifts from reality, turning registration into an operational liability rather than a source of truth.

The challenges intensify when MCP servers operate across multiple trust boundaries, including contractors, remote developers, unmanaged devices, and external partners. In these situations, it becomes nearly impossible to enforce who should register a client or maintain server-stored metadata as authoritative. This is precisely what the team in our story encountered: internal and external clients behaved so differently that a single onboarding model could not reliably support both. These tensions reveal the limits of DCR in modern MCP ecosystems and explain why teams begin looking for a more flexible alternative.

Understanding Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) in practical MCP deployments

Dynamic Client Registration is valuable in MCP because it gives platforms a predictable, auditable way to onboard clients. In the story we’ve been following, the dev team initially relied on DCR confidently. Their early clients, an internal code-review bot, a stable partner integration, and a versioned CLI utility fit neatly into DCR’s workflow. Each tool POSTed metadata to /register, the server issued a client_id, and the security team always knew exactly which clients had been approved.

DCR performs best in environments where stability and control are critical. These include tightly scoped enterprise systems and long-lived backend services. In these cases, the model provides clear operational advantages because:

- The server maintains a single source of truth for client metadata

- Security teams can audit registrations and track lifecycle changes.

- Administrators explicitly decide which clients are allowed to onboard

This controlled process is why OAuth ecosystems still depend heavily on registration-based identity.

Friction begins when MCP expands beyond the capabilities of existing tools. IDE extensions restart frequently, CI agents appear for only minutes, and developers testing prototypes trigger new registrations without realizing it. What was once a clean /register table turns into a high-churn store of stale entries, accidental duplicates, and outdated versions. This isn’t a failure of DCR itself; it’s a mismatch between DCR’s assumptions and the behavior of MCP clients operating in dynamic, fast-changing environments. DCR remains excellent for stable clients, just not for those that appear and mutate constantly.

Why MCP Needs Another Option Beyond Dynamic Client Registration

Dynamic Client Registration breaks down as soon as the MCP leaves tightly controlled environments. Traditional OAuth systems work because platforms know their clients in advance, enterprise SaaS apps, long-lived internal services, or fixed partner integrations with predictable lifecycles. MCP deployments look nothing like that. MCP servers increasingly interact with IDE extensions running on developer laptops, short-lived CI workers, AI agents that rewrite their capabilities, and experimental tools created hours earlier. Instead of a curated client list, teams face a constantly shifting surface.

Operational friction appears the moment these clients scale. Every POST to /register forces the server to store, validate, track, and govern metadata for tools that may exist only briefly. A VS Code extension reloads and registers again. A CI pipeline spins up workers that disappear minutes later. Experimental tools show up with outdated metadata. The registration database becomes an accidental source of truth for identities it was never meant to own, filling with duplicates, abandoned entries, and conflicting versions. This is where teams begin to encounter client sprawl and metadata drift, not because DCR is flawed, but because its assumptions no longer align with MCP reality.

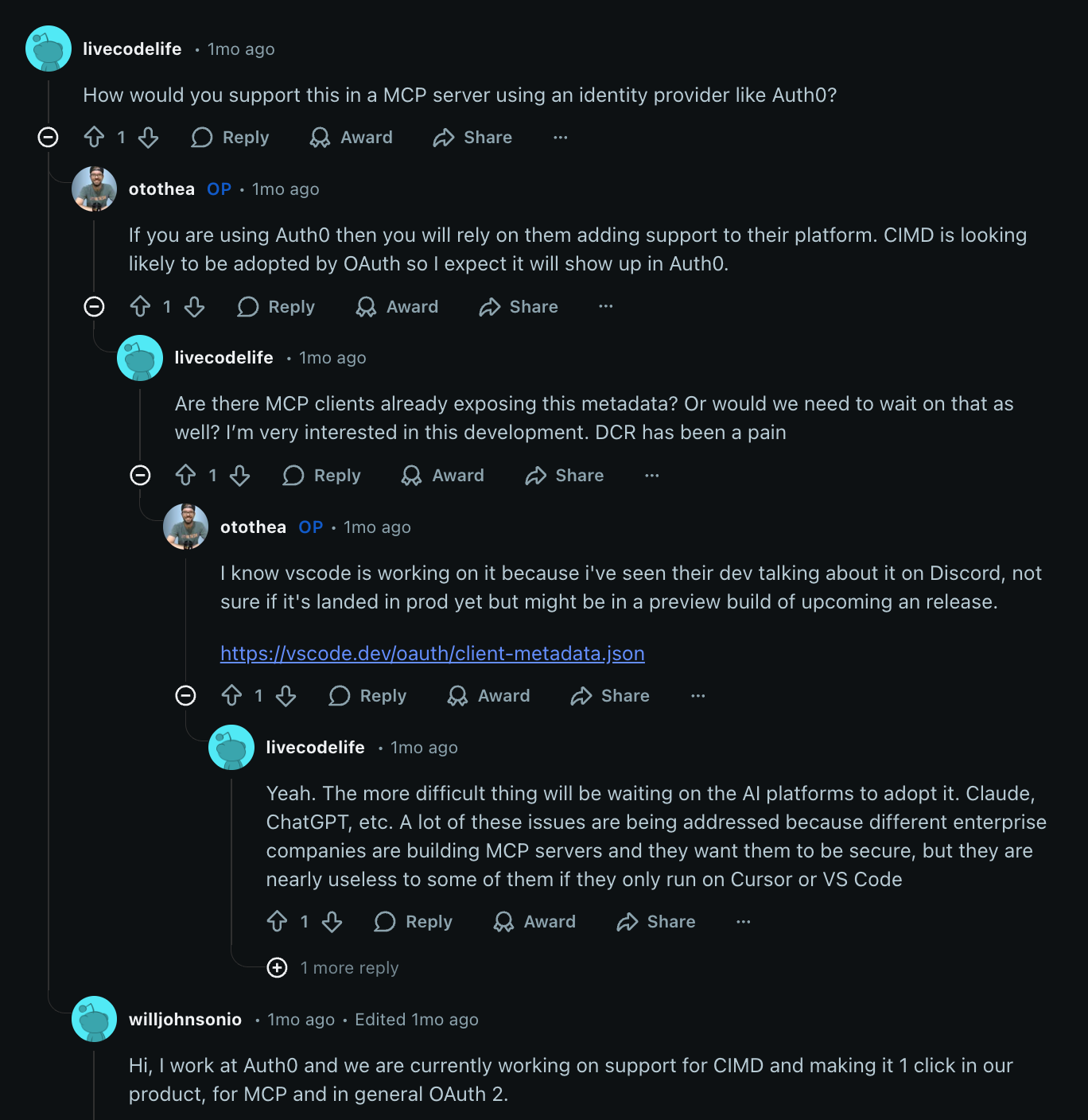

This tension is now visible across the MCP ecosystem, not just inside individual teams. As MCP moves from prototypes into real deployments, engineers are openly questioning how client identity should work for agent-heavy systems. Discussions across MCP communities show recurring themes: how to support metadata-based identity with existing identity providers, whether IDEs are currently exposing client metadata, and how to avoid making registration endpoints the weakest link in an otherwise secure system.

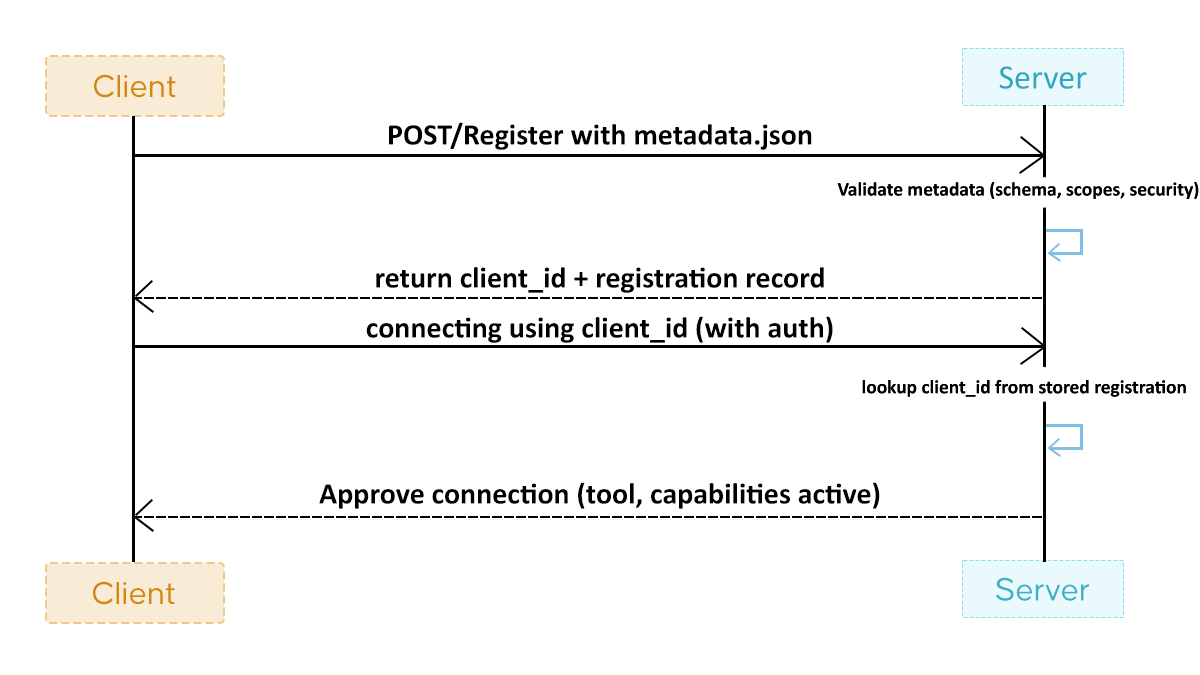

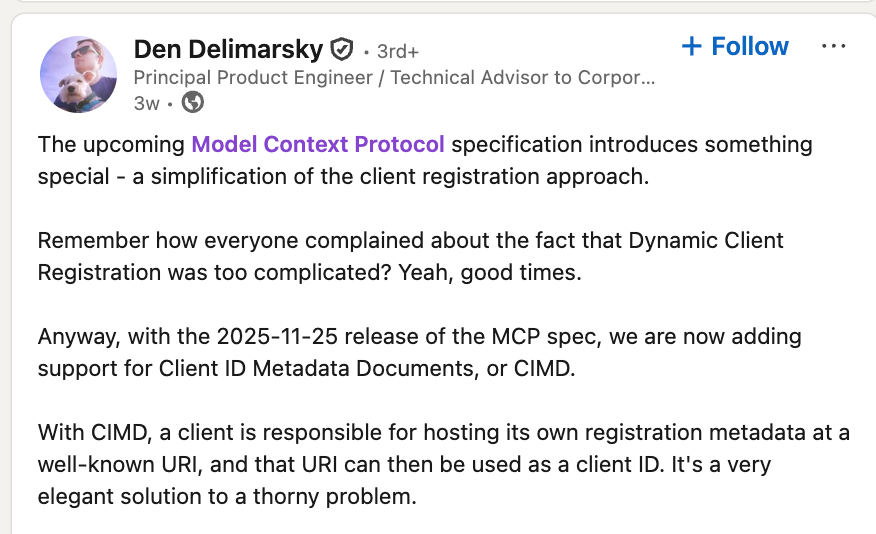

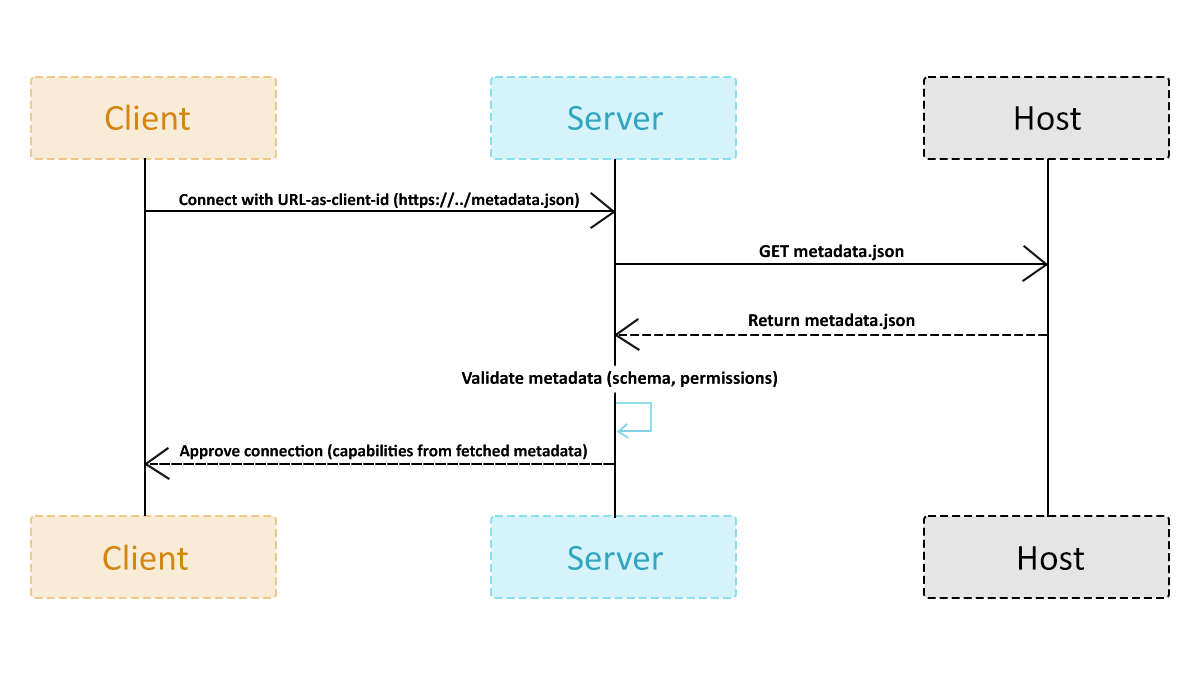

The MCP specification itself reflects this shift. With the November 2025 update, MCP introduced support for Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD), formalizing a second identity model alongside DCR. Instead of forcing every client to register and persist server-side state, CIMD allows a client to host its own metadata at a well-known URL and use that URL as its identity. This change directly maps to real deployment patterns: short-lived agents, local developer tools, IDE extensions, and experimental clients that do not fit traditional registration flows.

The important takeaway is not that DCR was replaced. DCR still works exceptionally well for curated, long-lived, and high-governance clients. What changed is that MCP deployments outgrew a single, registration-centric identity model. The question teams are now asking is no longer “DCR or CIMD?” but rather: how do we support both without forcing every client into the same onboarding shape?

That is the context this blog addresses, grounding the DCR vs CIMD discussion in real deployment pressure, explaining where each model fits, and showing how modern MCP platforms handle both cleanly without exposing brittle registration surfaces or sacrificing governance.

Why CIMD Solves the “Too Many Clients, Too Little Control” Problem in MCP

CIMD reduces identity friction in fast-changing MCP ecosystems. MCP deployments quickly attract clients that are unpredictable, short-lived, and user-local, making it unrealistic for dev teams to maintain server-stored registrations. CIMD avoids this bottleneck by allowing each client to self-describe via a hosted metadata document rather than relying on persistent server-side records. This shifts client identity from a static table to a dynamic, fetch-on-demand model.

CIMD eliminates the operational overhead that DCR struggles with at scale. In our running story, the team immediately saw this: IDE plugins restarted frequently, CI pipelines spun up agents for minutes at a time, and prototype tools changed capabilities daily. None of these clients was stable enough to justify persistent registrations. With CIMD, identity is lived with the client, restoring clarity and eliminating cleanup work.

Key sources of friction that CIMD removes include:

- No repeated registration events from tools restarting or reconfiguring themselves

- No stale, duplicate, or orphaned entries in the registration database

- No accidental mutations to server-maintained metadata

- No admin intervention for short-lived or local clients

CIMD scales naturally across internal, open-source, and platform ecosystems. Internal teams can publish CLI tools without waiting for platform engineering. Open-source contributors can run local MCP clients without requesting credentials, and platform builders can support hundreds of agents, extensions, and developer workflows without exposing a public /register endpoint.

This is why CIMD doesn’t replace DCR; it completes it. DCR remains the right model for vetted, long-lived, high-governance clients. CIMD covers the opposite end of the spectrum: unpredictable, fast-moving, distributed tools. Platforms like Scalekit make this hybrid reality seamless, allowing teams to adopt CIMD where flexibility matters while continuing to rely on DCR where governance is essential, all through a unified onboarding layer.

How Scalekit Makes DCR and CIMD Easy to Use in MCP Deployments

Scalekit streamlines MCP onboarding by supporting both Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) and Client-Initiated Metadata Documents (CIMD) out of the box. Instead of forcing teams to redesign their identity workflow for every new tool, Scalekit provides a unified layer that lets predictable clients onboard through DCR while fast-changing or external tools authenticate through CIMD without additional infrastructure effort.

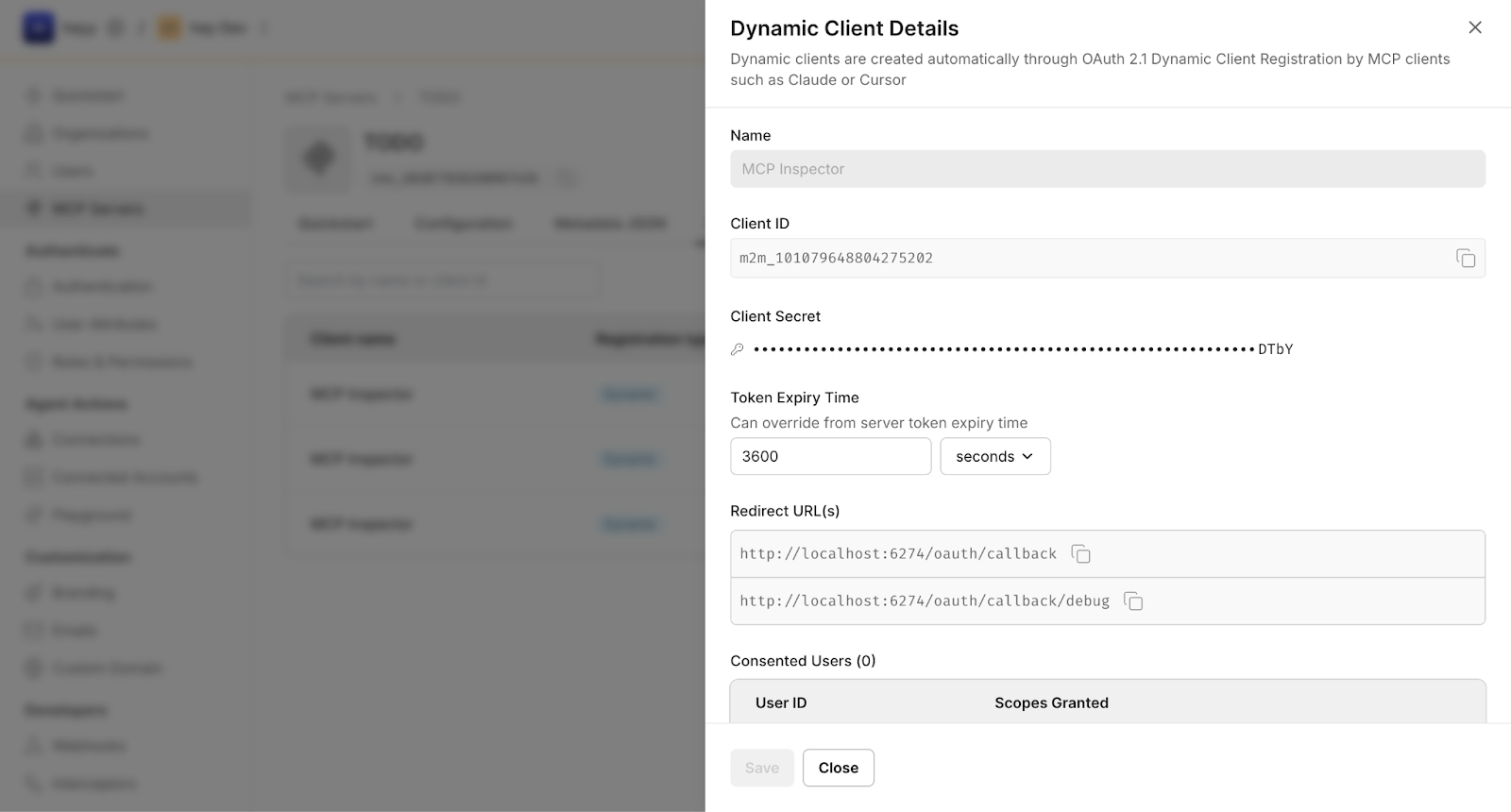

How DCR Works on Scalekit

Scalekit automatically handles DCR for MCP clients that support the OAuth registration flow, such as Claude Desktop, OpenAI, VS Code MCP extensions, Cursor, and most modern IDE agents.

DCR on Scalekit gives you:

- Automatic onboarding via /register with no manual setup

- A server-generated client_id and audit trail

- Centralized visibility into registered clients

- Choice between authorization-code or client-credentials OAuth flows

If you want greater control, Scalekit also lets you pre-register specific clients in the dashboard, ensuring only vetted tools can authenticate.

Here is how a Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) connection appears in the Scalekit dashboard after a client onboards via /register.

How CIMD Works on Scalekit

For tools that cannot or should not be pre-registered, local CLI tools, experimental MCP agents, CI runners, or plugins under active development, Scalekit enables authentication via a metadata URL.

CIMD on Scalekit lets clients:

- Use a URL as their identifier

- Host metadata in GitHub, S3, localhost, or any HTTPS location

- Authenticate without needing dev teams to mint IDs

- Connect repeatedly without registering new versions

This keeps onboarding lightweight even when clients mutate frequently.

Below is a quick overview of how DCR and CIMD appear in Scalekit when clients register or connect to your MCP server.

Why This Matters for Engineering Teams

Most organizations deploying MCP eventually operate a hybrid ecosystem: curated internal tools that benefit from DCR and dynamic, developer-facing clients that better fit CIMD. Scalekit removes the burden of choosing by supporting both paths natively.

Teams can onboard stable clients through DCR, enable high-churn clients through CIMD, and keep identity management clean without rewriting authentication logic.

Scenario-Based Comparison: When Each Model Makes Sense

Choosing between DCR and CIMD becomes easier once you map your deployment to real-world patterns. In the lead-up story, the internal dev team discovered that different parts of their ecosystem behaved differently: their partner systems were predictable, their CI agents were not, and their developer tools fell somewhere in between. Rather than treating onboarding as a single problem, they realized that each environment required its own identity model.

To make this concrete, the table below distills the most common MCP deployment patterns and the identity model that aligns best with each. The goal isn’t to prescribe a universal rule but to help teams recognize the shape of their ecosystem.

Across these scenarios, a clear pattern emerges: governed environments benefit from DCR, high-churn environments benefit from CIMD, and hybrid environments need both. Platforms such as Scalekit operationalize this principle by offering seamless support for both models. Teams get the reliability of DCR, where identity must be controlled, and the agility of CIMD, where clients are fluid without maintaining separate onboarding pipelines.

Real-World Pain Points Engineers Run Into With DCR and CIMD

Real engineering teams discover the limits of both client-identity models as soon as their MCP deployment grows beyond a few controlled tools. These issues rarely appear in design diagrams; they surface when developers run IDE plugins locally, automation pipelines spin up temporary agents, or partner systems behave in slightly unexpected ways. Understanding these pain points is essential before choosing an onboarding approach.

DCR creates friction when client ecosystems are unpredictable.

Dynamic Client Registration assumes you can manage a curated set of clients, but modern MCP environments challenge that assumption immediately. IDE extensions restart frequently and re-register themselves; CI runners are available for only a few minutes at a time; and internal tools may regenerate capabilities based on runtime configuration. Each of these moments triggers new or duplicate entries in the server’s registration store. Without careful lifecycle policies, the registration table quickly fills with abandoned or conflicting identities, all of which the dev team must audit, clean, or reconcile later.

CIMD introduces a different operational challenge: metadata fragmentation.

CIMD removes the burden of registration but shifts responsibility to client developers. When metadata is hosted across GitHub repos, S3 buckets, internal servers, and local environments, its lifecycle becomes harder to supervise. Some URLs move or disappear, some metadata files are edited without versioning, and some long-running agents cache outdated content. These issues do not break the model; CIMD remains powerful for dynamic clients, but they highlight that decentralization comes with its own coordination overhead.

Most enterprises ultimately need both models, and Scalekit is designed around this reality.

Internal, long-lived clients benefit from the auditability and administrative governance that DCR provides. External clients, experimental extensions, and short-lived developer workflows benefit from CIMD’s lightweight, self-declared identity. Scalekit supports this hybrid pattern natively, allowing teams to adopt DCR where stability matters and CIMD where flexibility is essential without engineering separate authentication stacks or managing inconsistent onboarding logic. The result is a deployment model that stays operationally clean even as client diversity grows.

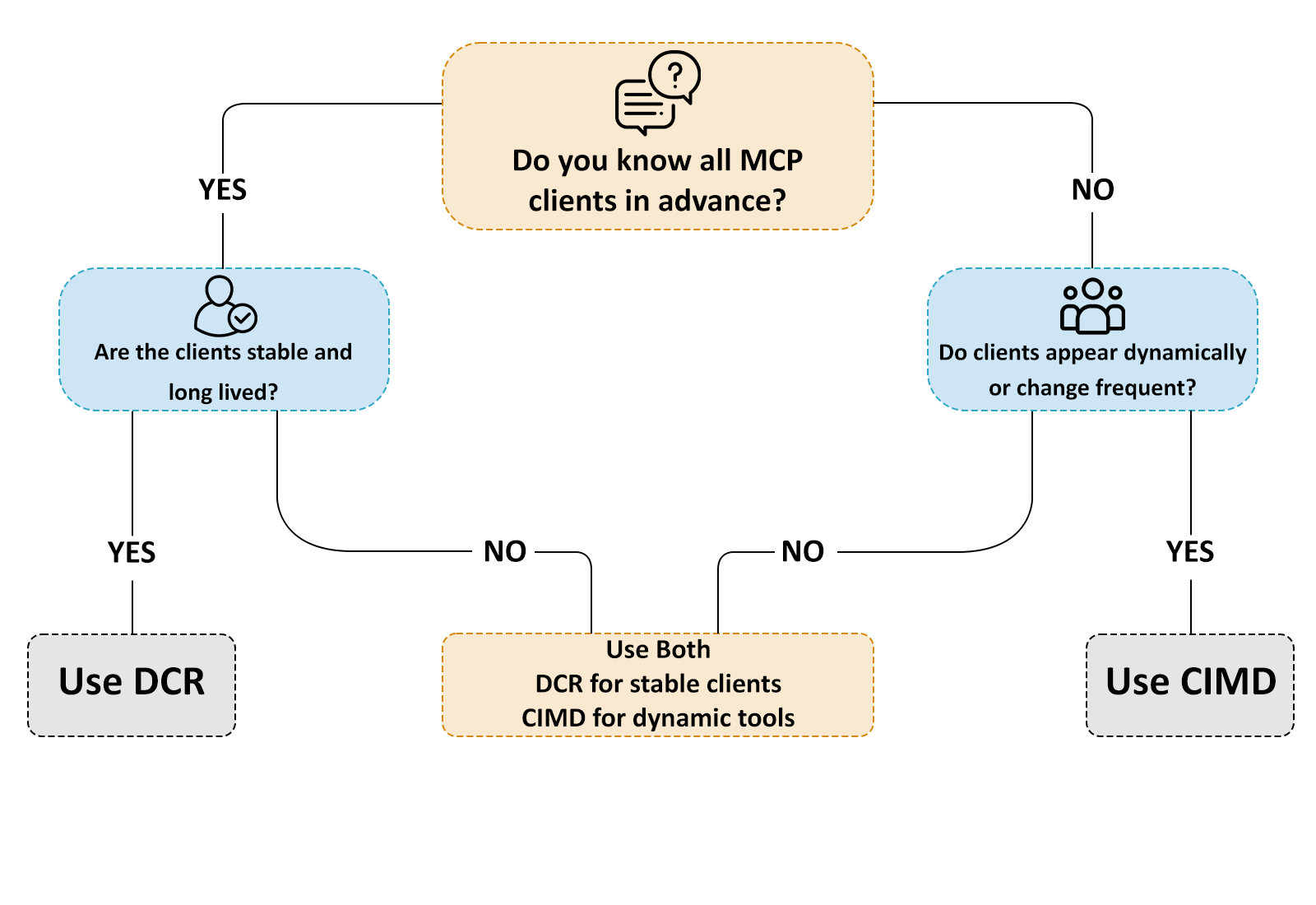

A Simple, Developer-Friendly Decision Path for Choosing Between CIMD and DCR

Engineering teams often reach the exact moment: “We understand both models… but which one should we actually implement for our MCP deployment?”

This section converts the earlier scenarios, trade-offs, and pain points into a clear decision tree that mirrors the real-world architecture conversations inside dev teams.

The goal is not to crown a “winner.” Instead, this decision tree helps teams select a model that aligns with their ecosystem, risk appetite, and the lifecycle of clients interacting with their MCP server. Whether you are building a public-facing MCP layer, internal automation tooling, or an IDE extension, this flow provides a repeatable way to justify your choice to stakeholders.

The diagram below captures the high-level reasoning that backend/dev teams at large companies use when evaluating auth and client onboarding strategies.

Conclusion

Modern MCP deployments won’t succeed by betting on a single identity model. DCR and CIMD solve different problems, and the realities of today’s engineering environments, distributed IDEs, fast-spawning agents, partner integrations, and cloud-hosted MCP servers demand that both options remain on the table. Teams that understand when each model shines will avoid authentication bottlenecks and metadata sprawl that are already surfacing in early MCP implementations.

For a platform like Scalekit, which focuses on making MCP adoption seamless across enterprise systems, IDEs, and autonomous agents, supporting both flows is more than a technical detail; it is a strategic capability. Scalekit enables companies to onboard curated clients through DCR when control is essential, while also unlocking CIMD for dynamic, unpredictable, or large-scale ecosystems. This dual approach removes friction for developers, keeps infra teams confident, and future-proofs MCP deployments as the client landscape grows more diverse.

If you’re evaluating MCP adoption within your organization, the next step is straightforward: design your authentication layer to support DCR and CIMD side by side, and let your deployment context dictate which takes precedence. Scalekit provides the tooling, guardrails, and automation to make this dual-model approach seamless so engineers can spend less time wrestling with identity mechanics and more time shipping features. For teams interested in a deeper dive into URL-based identity, our blog Client ID Metadata walks through CIMD in detail.

FAQs

1. How are CIMD and DCR different at a practical level?

CIMD removes the registration step entirely by treating a URL as the client’s identity and pulling metadata dynamically from that location. DCR requires each client to register at/register, obtain a client_id, and authenticate using stored metadata. In practice, CIMD feels lightweight and stateless, while DCR behaves more like a traditional OAuth-style onboarding flow with server-side persistence.

2. When does DCR remain the safer and simpler choice?

DCR remains the easier model when the ecosystem is closed or curated, such as internal enterprise platforms, vetted partners, or tools where every client is known in advance. It provides predictable metadata storage, explicit registration, and substantial administrative control. Many organizations continue to rely on DCR because it fits environments where identity governance is strict and every client must be approved.

3. Why do open MCP deployments lean toward CIMD?

Open MCP deployments often expose capabilities to a wide range of IDEs, agents, plugins, and automation tools. In these environments, pre-registration becomes a bottleneck and an operational risk, especially when clients are short-lived or unknown. CIMD eliminates the need to manage large sets of client records and reduces the attack surface by avoiding a public /register endpoint. This makes it the preferred model for marketplaces, CLI agents, and fast-moving developer tooling networks.

4. How does Scalekit help teams choose between CIMD and DCR?

Scalekit approaches identity as a deployment choice rather than a forced standard. Teams can adopt CIMD for high-churn or public-facing MCP clients while still using DCR for stable internal tools. The platform provides abstractions that make both flows consistent, monitored, and secure, so engineers avoid building custom authentication logic repeatedly across environments.

5. Why does Scalekit recommend supporting both modes instead of picking one?

Most engineering teams serve a hybrid ecosystem of internal agents, marketplace clients, browser extensions, IDE plugins, and embedded tools. Scalekit has observed that no single identity model fits all of these simultaneously. By supporting CIMD and DCR side-by-side, companies gain long-term flexibility: enterprise-controlled workflows get the reliability of DCR. At the same time, external or short-lived clients benefit from CIMD’s simplicity. This dual-mode support keeps MCP integrations stable as the ecosystem evolves.