Client ID Metadata: How MCP clients authenticate without registration

TL;DR

- The Model Context Protocol (MCP) creates a huge number of unpredictable clients, IDEs, CLIs, browser extensions, AI agents, community tools, and short-lived automation jobs. Preregistering all of them in OAuth is impossible.

- CIMD changes client_id into a URL that hosts the client’s metadata. The MCP server fetches this URL instead of looking up a client in a database.

- CIMD turns thousands of VS Code instances into one recognized client by letting them share a single metadata URL. Registration becomes more predictable rather than exploding with new entries.

- All OAuth details, redirect URIs, PKCE, JWKS, and client type come from the metadata file, not from server-side configuration.

- CIMD only solves client registration. MCP servers still validate tokens for their own audience; access to downstream services (like GitHub) must happen server-side.

Why CIMD Matters: Fixing registration for dynamic MCP clients

The MCP ecosystem has shifted from local experiments to real workloads running across IDEs, agents, SaaS platforms, and internal developer tools. As adoption grows, a recurring bottleneck appears: MCP clients multiply quickly and unpredictably, and traditional OAuth preregistration cannot keep up.

To address this, the November 2025 MCP auth spec introduced Client ID Metadata (CIMD), a model in which client_id is a URL pointing to the client’s metadata. MCP servers fetch this document, validate it, and drive OAuth dynamically instead of relying on static client entries.

Consider NimbusScale, a fictional cloud cost-optimization SaaS. NimbusScale built an MCP extension for VS Code and Cursor to enable developers to query deployment costs directly from their IDE. They expected to register the extension once. Instead, every IDE instance, CI agent, and local test environment behaved as a separate OAuth client, each with its own redirect URI and runtime quirks. Their client registry became unmanageable within days.

This blog explains why registration breaks in MCP, what CIMD actually provides, how a CIMD-based OAuth flow works, where CIMD helps in real deployments, and the operational challenges teams must plan for.

MCP’s real-world growth exposes registration gaps

NimbusScale, a fictional B2B cloud cost-optimization platform, recently rolled out an MCP extension for VS Code and Cursor, expecting to register it once and rely on a familiar OAuth flow. But as soon as developers began using it, every IDE session behaved like a separate OAuth client. Within days, NimbusScale saw hundreds of distinct clients: local IDE instances, internal staging builds, CI jobs running cost checks, and short-lived analysis agents created during deployments. The traditional “one client, one registration” model broke instantly because no one could predict how many MCP clients would exist or where they would originate.

This pattern only intensified as MCP adoption grew. Plugins ran across thousands of machines, MCP servers sat behind load balancers, and internal teams built lightweight agents that appeared and disappeared throughout the day. The registration surface started to resemble a large distributed OAuth ecosystem rather than a single integration. Static preregistration, redirect allowlists, and manual onboarding simply couldn’t keep pace with clients whose identities changed across machines, ports, and environments.

For a step-by-step implementation guide, see our MCP quickstart and learn how to implement OAuth for MCP servers.

CIMD addresses this by redefining client_id as a URL that hosts the client’s metadata. Instead of maintaining a sprawling database of client registrations, the MCP server fetches and validates this metadata at runtime. Redirect URIs, PKCE settings, JWKS locations, and application type are defined in the metadata itself, not in server-side entries that quickly become stale. CIMD isn’t a universal identity solution, but it is a practical way to handle MCP’s reality: clients are numerous, diverse, unpredictable, and often short-lived.

Why client registration is hard in MCP

Traditional OAuth assumes you know your clients in advance. MCP breaks this the moment it’s deployed.

When NimbusScale shipped its MCP extension for VS Code and Cursor, the identity team expected to register the extension once. Instead, every developer's laptop behaved like a different OAuth client. Each IDE ran on a different port, behind different VPN rules, proxies, or firewalls. Redirect URIs changed constantly, and the identity team could not maintain a stable allowlist.

Then the real enterprise complexity showed up:

- CLI tools and browser extensions started calling the MCP server with their own redirect patterns.

- Internal scripts and cost-check utilities behaved as independent clients, even though they were built by the same team.

- CI jobs and ephemeral agents spawned clients that existed for only a few minutes, far too short to preregister.

In a week, NimbusScale went from “one extension” to hundreds of unpredictable clients that no administrator could track or approve. The preregistration database was filled with stale entries, redirects no longer matched reality, and teams couldn’t reliably determine which client was which.

The core issue is simple: MCP doesn’t have a fixed set of clients. It has a constantly changing stream of them. This is why static, database-driven OAuth registration falls apart in real MCP deployments and why CIMD becomes necessary.

What CIMD actually is in the MCP ecosystem

CIMD exists because MCP clients do not behave like traditional OAuth applications. In MCP, a “client” might be a VS Code extension running on a random loopback port, a CLI tool used by hundreds of developers, a browser-based MCP client embedded in an internal dashboard, or an automation agent spun up for only a few minutes. These clients appear, evolve, and disappear far too quickly for any platform team to preregister individually.

CIMD addresses this by redefining the meaning of client_id.

Instead of storing a client ID in a server-side registry, client_id becomes a URL that points to a JSON metadata document. When the client begins authentication, the MCP server retrieves this document, validates it, and uses it to run the OAuth flow. This shifts registration from server-maintained to client-published, aligning with how MCP tools actually behave.

How CIMD fits real MCP use cases

CIMD maps cleanly to the kinds of MCP clients that show up in real deployments:

- IDE extensions (VS Code, Cursor): Each instance runs locally with its own redirect URI. A single metadata URL allows all cases to authenticate without maintaining thousands of registry entries.

- CLI tools used across engineering teams: One metadata file can represent every copy of the CLI, regardless of how many developers install it.

- Browser-based MCP clients: Internal dashboards or thin web tools can authenticate cleanly without preregistration, simply by hosting metadata at a stable URL.

- Ephemeral automation agents: CI jobs, cleanup tasks, and internal bots reuse the same metadata URL on each run, perfect for clients that don’t live long enough to be registered.

- Community-built tools: Open-source MCP clients can join the ecosystem by publishing a simple metadata file, without requiring platform approval.

These are the environments where CIMD makes a measurable operational difference.

Traditional OAuth Registration (DCR) vs CIMD

This comparison reflects how MCP is actually used, not a theoretical OAuth model.

A minimal CIMD example

This single file can safely represent thousands of IDE instances, each running on its own machine with different ports or environments. When the client initiates authentication, the MCP server fetches the file via the client_id URL and proceeds based on the metadata it contains.

Why CIMD fits MCP’s reality

Traditional OAuth assumes that applications are predictable, long-lived, and under administrative control. MCP assumes the opposite:

- Clients multiply quickly

- Redirects differ across environments

- New tools appear without platform coordination

- Automation agents are short-lived

- Developers constantly modify and test local setups

CIMD embraces this reality. It lets the client describe itself, while the server validates that description at runtime, removing the operational bottlenecks that static preregistration creates.

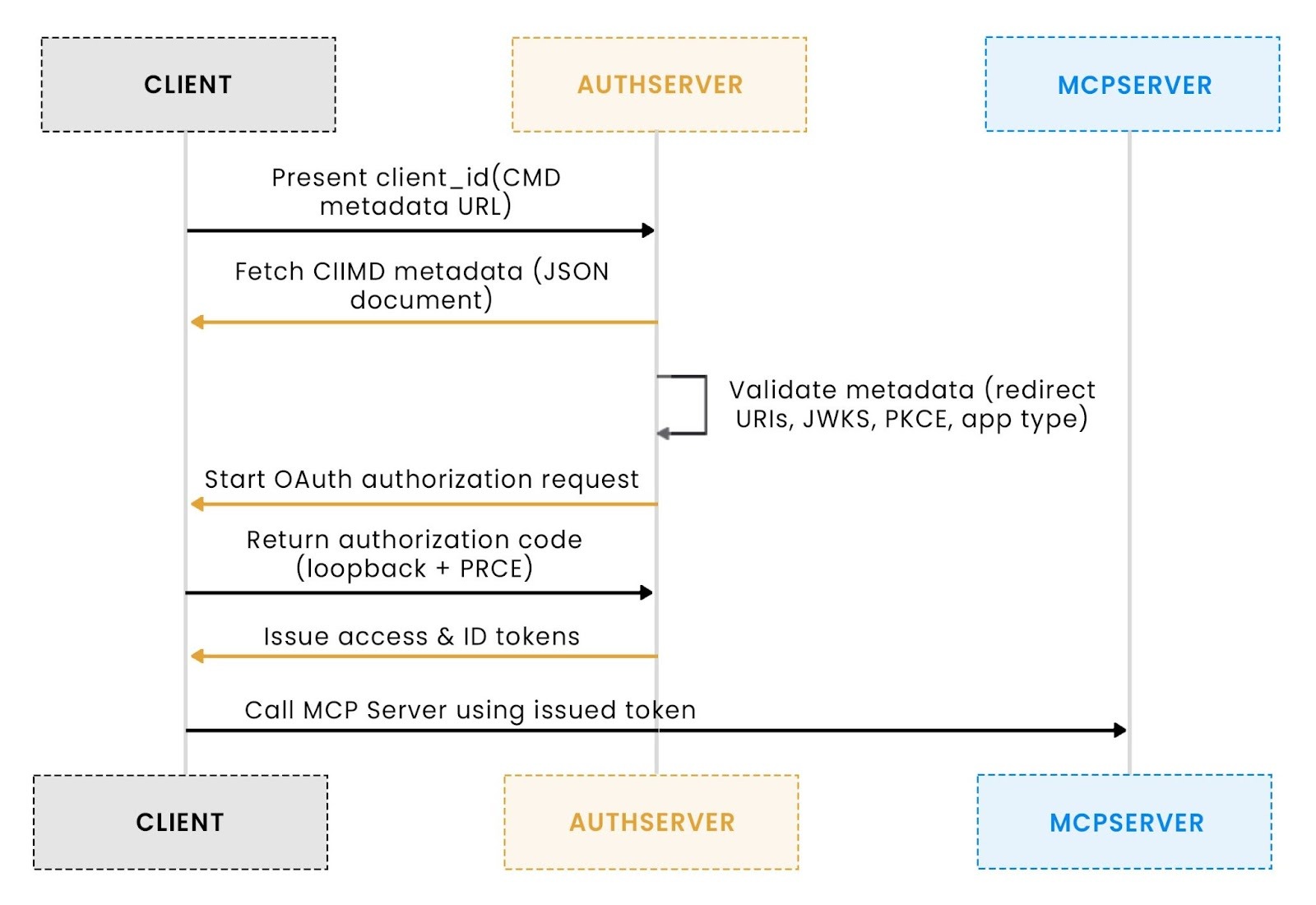

How a CIMD flow works

CIMD changes the MCP authentication flow by allowing a client to identify itself via a metadata URL rather than a preregistered/dynamic registered client entry. The authorization server fetches this document, validates it, and uses it to drive the OAuth process. The flow is straightforward when you see it end to end.

1. The client begins authentication by sending a metadata URL

When an MCP client (an IDE extension, CLI, or agent) begins authentication, it sends a client_id that is itself a URL:

This URL is the client identity.

2. The authorization server fetches and validates the CIMD document

Before any OAuth UI appears, the authorization server performs:

The fetched JSON describes how the client expects to authenticate, typically including:

- redirect_uris: where the authorization code should be delivered

- token_endpoint_auth_method: usually none for PKCE-based public clients

- jwks_uri: where to find the client’s public keys

- application_type: browser, native, or web

This validation step ensures the client is structurally sound and prevents misconfigured or untrusted metadata from entering the flow.

3. OAuth proceeds using the metadata values, not server-stored configuration

Once the metadata is validated, the Authorization Server builds a standard OAuth authorization request using the values provided by the client:

- The redirect URI comes from the metadata

- The client sends the PKCE challenge

- The loopback or local callback is validated using the metadata

- Key discovery uses the JWKS URI for JWT validation

Even if clients run on different machines with different ports or environments, they behave consistently because they all reference the same authoritative metadata URL.

4. The authorization server issues tokens without consulting a preregistration database

After successful authorization:

- The authorization server exchanges the code

- Tokens are issued (access token, optional refresh token)

- The client then calls the MCP server.

At no point does the server reference a stored client configuration.

CIMD replaces the concept of a static client registry entirely. This enables MCP clients, such as IDE extensions, CLIs, ephemeral agents, and automation tools, to authenticate reliably without overwhelming administrators with thousands of client entries.

Summarizing the CIMD flow

This flow mirrors real MCP deployments: dynamic clients, changing redirects, and no reliance on fragile preregistration workflows.

Where CIMD helps in real MCP deployments

CIMD delivers real impact in environments where MCP clients appear faster than any platform team can preregister them. NimbusScale’s rollout demonstrated this clearly: once MCP tooling was released internally, new clients emerged daily, with IDEs on different ports, experimental AI agents, customer-built scripts, and open-source utilities. CIMD allowed the server to evaluate these clients dynamically, without expanding a fragile registry or slowing down development.

1. Public SaaS MCP servers need a way to accept unplanned clients

NimbusScale exposes an MCP API surface to enterprise customers who bring their own tools, VS Code extensions, internal CLIs, browser-based agents, and custom scripts tied to their workflows. Since NimbusScale cannot preregister every tool used by every customer, CIMD became the only scalable option. Each customer tool simply publishes a metadata URL; the NimbusScale MCP server fetches it, validates it, and proceeds with OAuth. No onboarding tickets, no registry sprawl, and no assumptions about what clients customers will build next.

2. Local IDE extensions behave as separate clients and cannot be preregistered

When NimbusScale shipped its official VS Code extension, engineers quickly realized that each IDE instance launched with a different loopback redirect port. Across the company, more than 400 unique redirect URIs appeared in a single week, making preregistration mathematically impossible. By hosting a single CIMD document for the extension, NimbusScale gave every IDE instance a consistent way to authenticate, regardless of machine, OS, port, or version. The server validated behavior directly from the metadata, eliminating thousands of potential client entries.

3. Community tools and open-source clients must work without platform approval

Once NimbusScale published its MCP schema publicly, community developers started creating CLI utilities, browser add-ons, and lightweight automation bots. These tools did not go through internal review, did not request permission, and did not follow a predictable release process. CIMD enabled the platform to remain open: community authors placed a metadata file in their repo, and NimbusScale’s MCP server evaluated it at runtime. This preserved flexibility while maintaining security boundaries rooted in OAuth validation rules.

Practical challenges teams should expect when using CIMD

CIMD removes the overhead of preregistering thousands of MCP clients, but it also introduces operational realities that become obvious once MCP is deployed at scale. NimbusScale’s internal rollout surfaced a predictable set of challenges, none of them theoretical, all of them grounded in how real teams build and operate large systems.

1. Reliable hosting becomes a critical part of authentication

Because CIMD fetches metadata at runtime, authentication succeeds only if the metadata URL is reachable. NimbusScale initially hosted metadata for its VS Code extension on GitHub Pages; even a brief outage caused every login attempt across engineering to fail. This taught the team that CIMD metadata must be treated like production configuration: version-controlled, monitored, and hosted on infrastructure with predictable uptime. Once metadata becomes part of the auth flow, availability is no longer optional; it is identity.

2. Metadata fetching introduces SSRF and network-boundary risks

Since the client provides the metadata URL, the server must assume it is untrusted. During NimbusScale’s rollout, several developers accidentally configured test builds to reference localhost URLs or internal IP ranges that the server should never access. This forced the platform team to implement strict SSRF protections, block private networks, require HTTPS, and enforce short timeouts. CIMD makes registration flexible, but it requires strong guardrails to protect the server’s network boundaries.

3. Caching improves performance but can cause version drift

Caching metadata avoids frequent fetches, but it also introduces a subtle problem: stale configuration. NimbusScale experienced intermittent authentication failures during a JWKS rotation because some environments cached the old metadata while others fetched the new version. Caching works well only when TTLs, invalidation rules, and key rotation policies are intentional. Otherwise, teams risk unpredictable behavior that is difficult to diagnose in production.

4. Teams must shift their mental model away from static registries

CIMD removes the familiar “client table” that identity teams are used to maintaining. NimbusScale’s engineers initially struggled with the idea that the server no longer stores client configuration; instead, it dynamically discovers it. Redirect URIs, JWKS locations, and application types come from metadata the client publishes not from an admin console. This shift simplifies large-scale deployments but requires teams to unlearn assumptions built around static preregistration models.

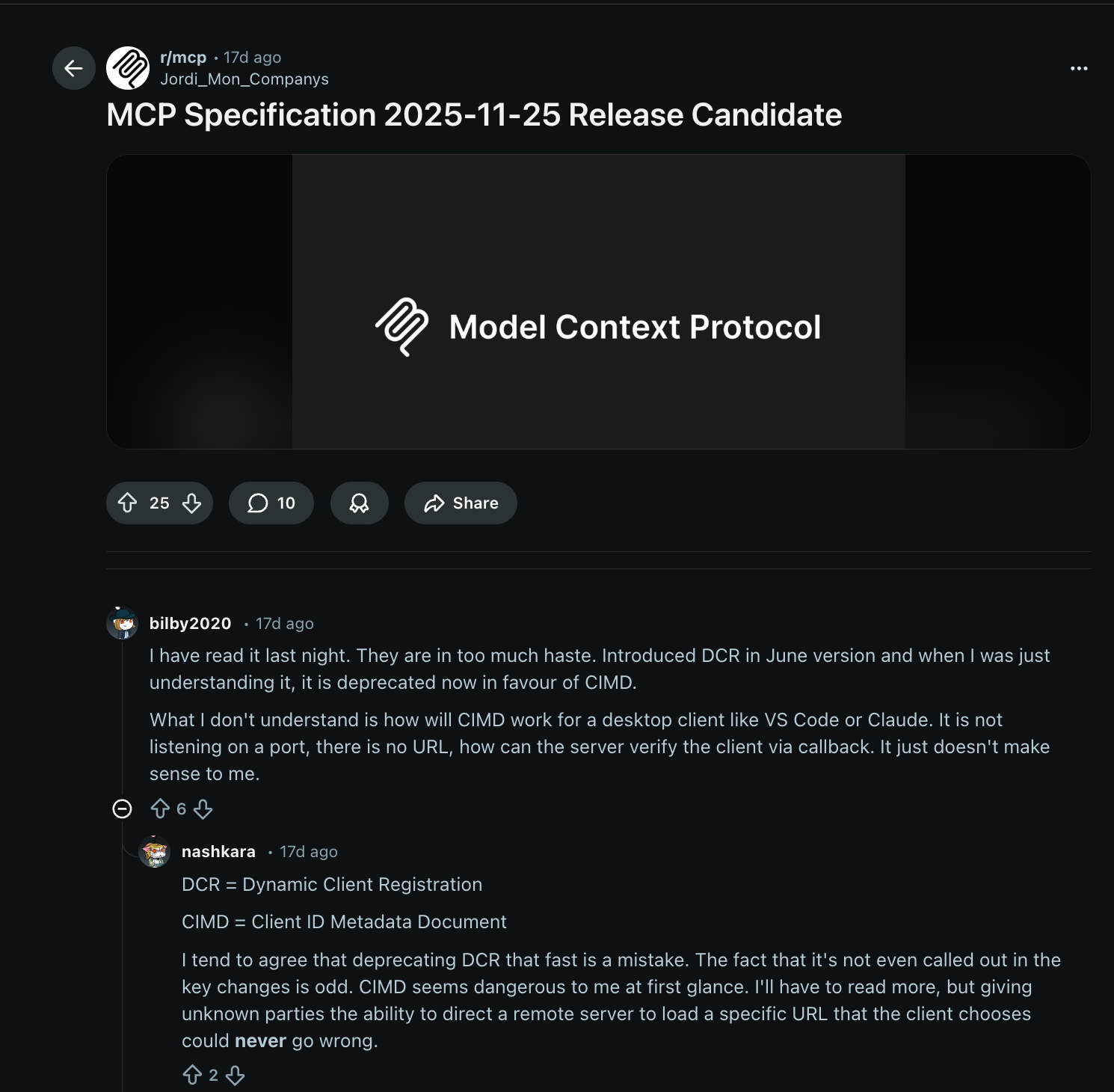

Community Insight: Enterprise identity questions emerging in MCP

A recent r/mcp discussion highlighted the identity challenges that appear when MCP moves from individual developers to enterprise deployments. Teams asked questions such as:

- “Can the MCP server reuse the GitHub token the IDE already has?”

- “Should the MCP server validate GitHub-issued tokens?”

- “If an agent talks to multiple MCP servers, does it need separate tokens?”

- “Do enterprise setups require on-behalf-of token flows?”

These questions reveal a consistent pattern:

MCP authentication is isolated from downstream API authentication.

An MCP server must validate the tokens it issues. Forwarding third-party tokens (like GitHub OAuth tokens) directly from the client is rarely correct; downstream access should be performed server-side, using tokens explicitly issued for that API or service.

Learn more about securing APIs with OAuth.

This distinction clarifies CIMD’s role: CIMD solves client registration and identity discovery, not cross-service authorization.

Enterprise deployments still rely on audience-scoped tokens, token exchange patterns, and explicit boundaries between MCP servers and external APIs.

How to publish a CIMD document safely and reliably

Publishing a CIMD document is straightforward in principle; it’s a JSON file at a URL, but it becomes operationally meaningful once real clients begin relying on it. The IDE rollout made this clear: once the extension went live, the metadata document behaved like a configuration API surface. The following patterns capture what teams found most reliable.

1. Static hosting gives small teams a predictable deployment path

Static hosting remains the simplest way to publish CIMD. A GitHub Pages site, a Vercel route, a Netlify static directory, or a small NGINX box can reliably serve a JSON file over HTTPS. The IDE rollout chose GitHub Pages because it provided version control, stable URLs, and automated deployment through pull requests. Static hosting works exceptionally well when metadata changes infrequently, but it still requires teams to monitor availability, TLS renewals, and propagation delays across environments.

2. Auth providers can host CIMD and JWKS when teams prefer managed infrastructure

Some teams reduce operational overhead by letting an identity provider host their CIMD and JWKS documents. This model centralizes metadata generation, key rotation, and version updates behind a single domain. During the IDE rollout, the platform team evaluated this approach after realizing the significant manual effort required to maintain JWKS files. Managed hosting simplifies operations but introduces a new dependency, so teams should weigh it against their existing infrastructure posture and desire for ownership.

3. Version control helps teams track metadata changes over time

Version control provides a durable audit trail for CIMD updates. Treating metadata as configuration enabled the IDE rollout team to review each change to redirect URIs, application types, or JWKS locations via standard pull requests. These reviews reduced the risk of accidental breakage and kept metadata aligned across environments. Static hosts integrate naturally with version control because deployments happen automatically after changes are merged, making the workflow dependable for both small and enterprise-scale teams.

4. JWKS hosting requires stability and thoughtful rotation policies

JWKS files must remain reachable and consistent for token validation to work. Hosting JWKS under the same domain as the CIMD document simplifies that requirement. Automated rotation helps strengthen security but demands predictable publishing and caching rules. During the IDE rollout, validation issues stemmed from mismatches between local and production keys, underscoring the need for careful key rotation and environment isolation. Whether using static hosting or a managed provider, key stability is non-negotiable.

5. Monitoring and deploying pipelines turn CIMD hosting into a reliable operational surface

Publishing a CIMD document is not a one-time task. A minor outage, such as the GitHub pages downtime the IDE team encountered, can interrupt login flows if the auth server cannot fetch metadata. Adding uptime alerts, TLS monitoring, version checks, and structured deployment pipelines helps ensure the metadata document behaves like the configuration surface it is. Treating CIMD hosting with the same rigor as other production configuration endpoints improves reliability for every client that depends on it.

Conclusion

CIMD gives MCP a registration model that finally matches how MCP clients behave in practice: distributed, short-lived, and constantly changing. NimbusScale’s rollout showed how quickly static preregistration breaks once thousands of IDE instances, scripts, and internal agents start acting as OAuth clients. By turning the client_id into a URL that hosts metadata, CIMD removes the need for massive registries while preserving the structure that MCP servers need to authenticate safely.

CIMD isn’t a replacement for OAuth fundamentals, and it doesn’t solve downstream authorization. Teams still need sound practices for metadata hosting, SSRF protections, caching rules, and token validation. But CIMD does eliminate the most significant operational bottleneck in MCP deployments: knowing in advance who your clients are.

If you’re evaluating MCP or planning an internal rollout, start small: publish a CIMD document for one tool, observe how your server evaluates it, and build from there. For deeper context, Aaron Parecki’s CIMD explainer remains the clearest walkthrough of how metadata-based registration fits into modern OAuth flows.

CIMD isn’t “the one true way,” but it is the most practical registration path for MCP’s open, fast-moving ecosystem. Experiment with it, refine it, and evolve your approach as your MCP footprint grows.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does CIMD replace Dynamic Client Registration (DCR)?

CIMD does not replace DCR; it simply fills a gap that DCR cannot address in the MCP ecosystem. DCR assumes every client can be preregistered in a database, which works for stable client populations but breaks down when MCP clients are IDE extensions, CLI tools, short-lived agents, or community utilities that appear without coordination. CIMD shifts registration to a URL-based metadata document, giving MCP servers the flexibility to authenticate clients they’ve never seen before. Teams can use CIMD and DCR side by side, depending on how predictable their client set is.

Should an MCP server trust downstream OAuth tokens (like GitHub tokens) passed by the client?

In almost all cases, no. MCP servers should validate only the tokens issued for the MCP server itself, not tokens intended for downstream APIs like GitHub. Passing a GitHub token through the client violates OAuth’s audience boundaries and complicates security reviews. The correct pattern is for the MCP server to handle GitHub access server-side, either via stored per-user GitHub tokens or via a GitHub App’s installation token for organization-level actions. If the server needs to act on behalf of the user, teams can use an on-behalf-of (OBO) flow to exchange the user’s MCP-audience token for a GitHub-audience token.

Does CIMD solve enterprise identity challenges by itself?

No. CIMD simplifies client registration, but it does not replace audience validation, JWKS management, or the token-exchange patterns that enterprise systems rely on. Teams still need to define how tokens are issued (audiences, scopes), how JWKS keys are rotated, how outbound metadata fetches avoid SSRF risks, and how multi-server authentication flows work when an agent interacts with several MCP servers. These concerns echo the fundamental questions raised in the MCP community, especially regarding OBO flows, proxy gateways, and whether the MCP server or the proxy should be the actual token validator.

Can Scalekit host CIMD and JWKS documents for my MCP clients?

Not automatically. CIMD metadata must be authored and hosted by the MCP client itself (e.g., VS Code, Cursor, a CLI) because the client controls its redirect URIs, keys, and behavior. Scalekit can reliably host your JWKS files and act as the authorization server that validates tokens, but it cannot generate CIMD documents on behalf of clients. The client publishes its own metadata; Scalekit simply supports authenticating against it.

Does Scalekit support MCP-specific flows, or do I need custom infrastructure?

Yes. Scalekit fully supports MCP authentication, including all three client registration models used in MCP today: pre-registered clients, Dynamic Client Registration (DCR), and Client ID Metadata (CIMD). You don’t need custom auth infrastructure — Scalekit already provides PKCE, audience-scoped tokens, JWKS hosting/rotation, and metadata hosting to make MCP servers work out of the box.