Auth0 for B2B SaaS: Where Multi-Tenancy Works, and Where Responsibility Shifts

TL;DR

- B2B authentication is about enforcing organization boundaries, not just logging users in.

- Auth0 supports B2B, but organization context, roles, and authorization must be assembled in application code.

- Token shaping, backend enforcement, and auditing shift long-term identity responsibility to the app.

- Incremental fixes (Actions, custom claims, duplicated checks) quietly make systems brittle over time.

- Org-first identity platforms like Scalekit centralize these guarantees and reduce application-level identity complexity.

Most B2B SaaS products do not start out needing complex authentication. Early on, a simple login flow works. Users sign in, permissions are basic, and everyone belongs to a single customer organization. Identity feels solved.

The problems begin when the second customer arrives. Suddenly, the same user may belong to multiple organizations. Roles stop being global. Enterprise customers ask for SSO. Auditors want to know who accessed what, which organization it was in, and when. Authentication still works, but correctness becomes harder to reason about.

This article walks through what B2B authentication actually requires, how those requirements are commonly implemented using Auth0, where complexity quietly accumulates over time, and how an org-first approach like Scalekit changes where that complexity lives. The goal is not to compare features, but to make the responsibility boundaries explicit.

What B2B authentication requires beyond basic login

B2B authentication is about enforcing organizational boundaries, not just identifying users. In consumer apps, login answers one question: who is this user? For B2B SaaS authentication, that is not enough. Every request must also specify which organization the user is acting on behalf of and what they are allowed to do within it.

Once a product supports more than one customer company, identity becomes contextual. Users are no longer global actors. Permissions stop being absolute. Everything is evaluated within an organization. At a minimum, B2B production authentication must consistently enforce the following primitives:

Organization as a hard security boundary

Organizations must define isolation. Data, permissions, and actions cannot cross org boundaries. An organization cannot be a UI filter or a soft grouping it must be enforced during authentication and authorization. Missing or incorrect org context is a security failure, not a degraded experience.

Roles scoped to organizations

Roles only make sense within an organization. The same user may be an admin in one org and read-only in another. Systems that treat roles as user-global must reintroduce scoping logic later in tokens, middleware, and permission checks.

Users belonging to multiple organizations

Multi-org users are common in B2B. Consultants, partners, and internal operators often span customers. Supporting this safely requires separating identity from context and treating org switching as a security transition, not a UI change.

Enterprise SSO per organization

SSO is negotiated at the org level. Each customer brings its own IdP, certificates, and policies. Supporting multiple concurrent SSO configurations requires org-aware routing and cannot be added cleanly after the fact.

Org-aware APIs, logs, and audits

Every authenticated action must be attributable to an organization. Logs and audit trails must reliably answer who did what, in which org, and when. If the org context is optional or inconsistently propagated, audits turn into manual investigations.

How Auth0 models B2B SaaS using tenants and organizations

Auth0 supports B2B by layering organizations on top of a tenant-centric identity model. Before writing code, it is important to understand how Auth0’s primitives are structured, because every B2B behavior you implement inherits these boundaries.

At the highest level, Auth0 assumes a single tenant as the root of trust. Everything else, applications, users, roles, and organizations, exists inside that tenant. B2B concepts are not first-class at the tenant level; they are added as contextual layers.

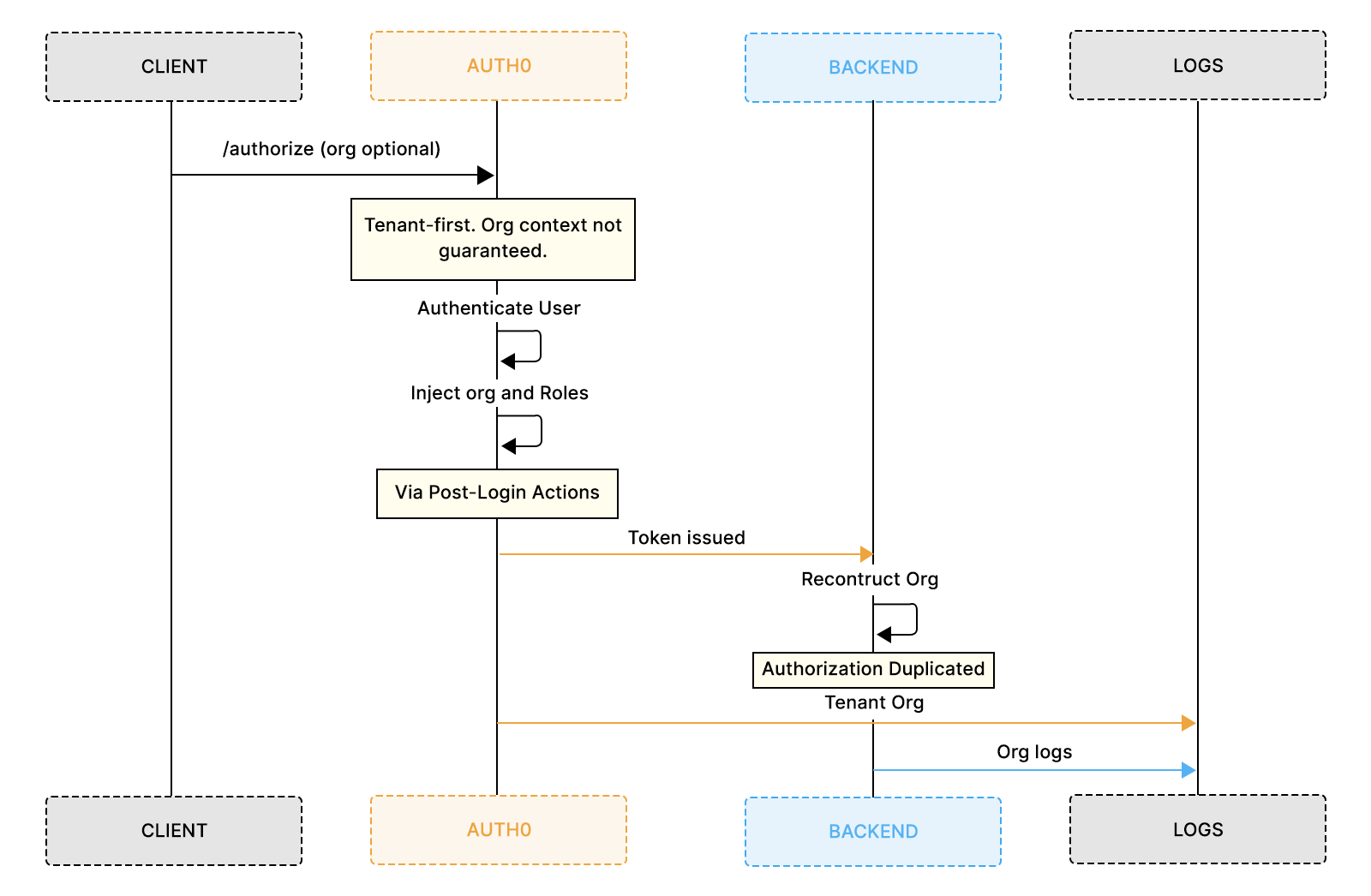

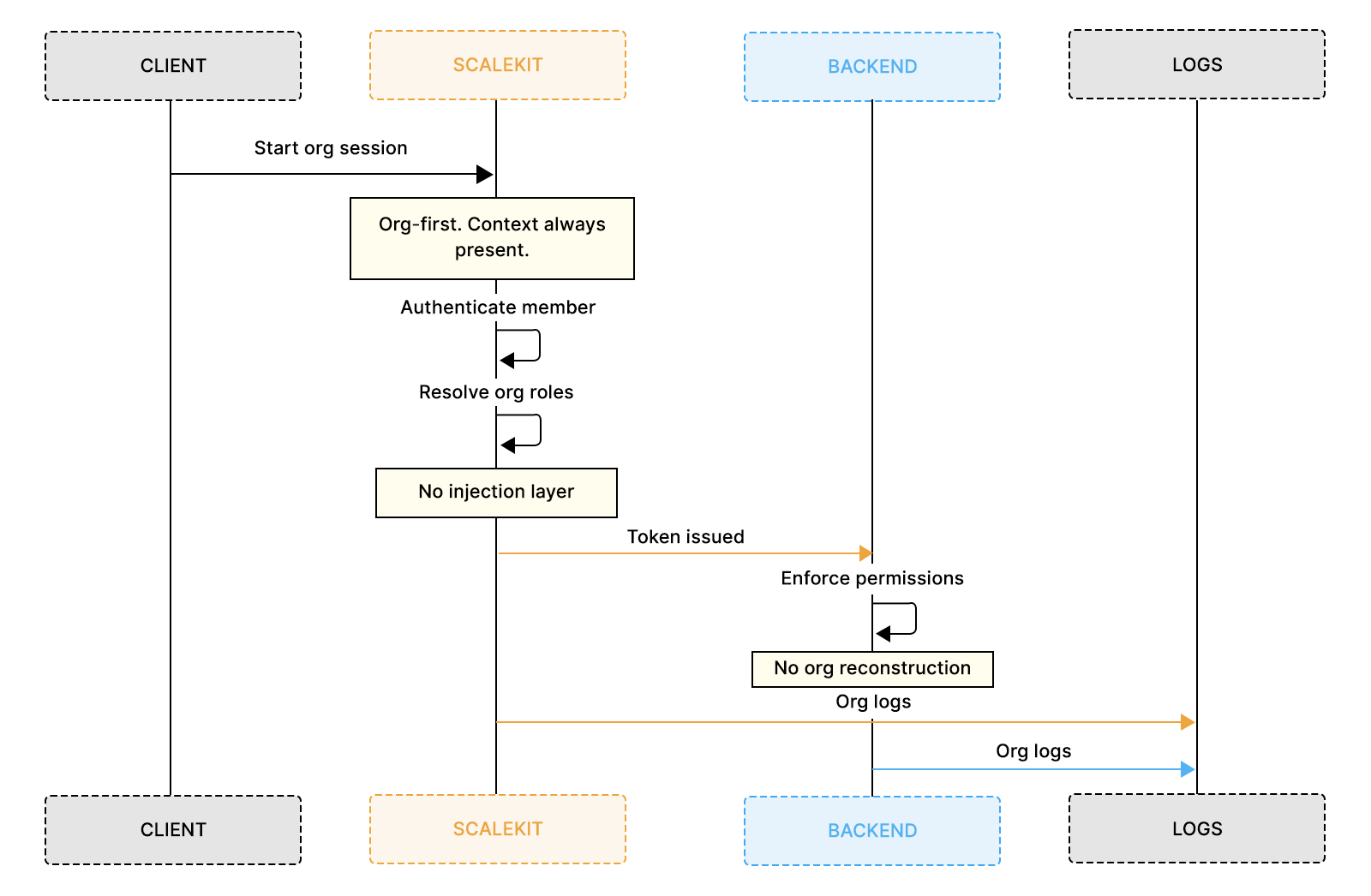

This design is flexible, but it shifts responsibility to the application to keep identity, organization context, and authorization aligned. The flow below shows how organization context flows through an Auth0-based B2B system and where responsibility shifts from the platform to the application.

Auth0 tenant as the global security container

The Auth0 tenant is the true security boundary. All users, applications, roles, and organizations live inside a single tenant. Authentication happens at this level first, before any organization context is applied. From Auth0’s perspective, a user always authenticates into the tenant, not into an organization. Organizations refine access, but they do not replace the tenant as the root identity scope.

This distinction explains many downstream behaviors, especially around tokens and logs.

Applications represent entry points, not customers

Applications define clients, not organizations. An Auth0 Application represents a login surface: a web app, mobile app, or API consumer. Applications are shared across all organizations in the tenant.

This means:

- Applications are not customer-specific

- Login configuration is reused across orgs

- Org context must be injected during authentication

B2B isolation does not come from applications; it comes later.

Organizations layer context on top of users

Organizations group users, but do not own identities. An Auth0 Organization is a container that:

- Groups users

- Enables org-specific SSO

- Associates roles in context

However, the user object itself remains tenant-scoped. The same user can belong to multiple organizations simultaneously.

This separation is powerful, but it requires careful handling in tokens and APIs.

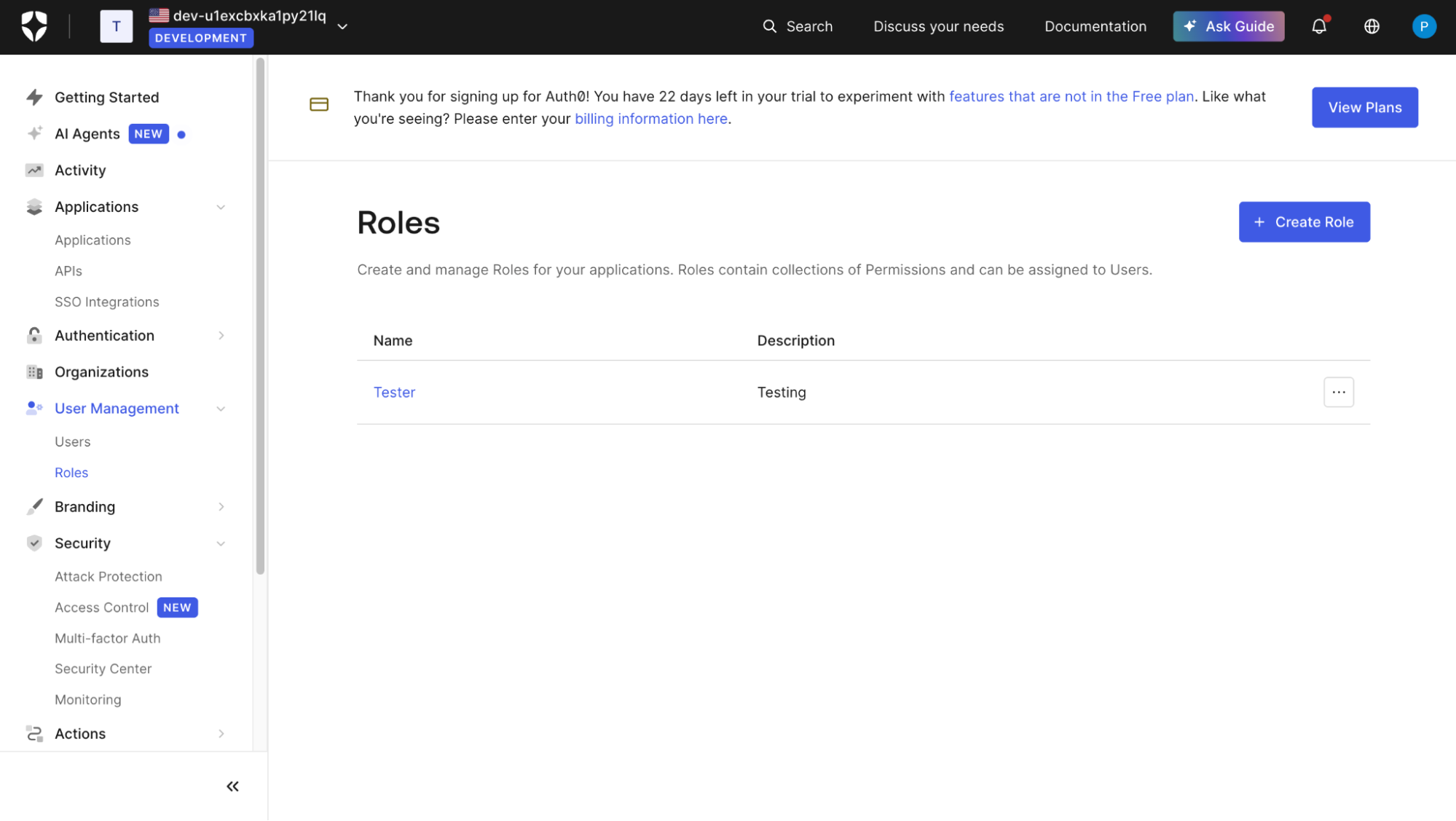

Roles are tenant-defined and reused across organizations

Roles exist globally, even when applied at the org level. Roles are defined once at the tenant level and then assigned to users within an organization context.

This means:

- Role names must be globally unique

- Role semantics must be consistent across orgs

- Per-org role customization requires conventions or tooling

Nothing prevents accidental reuse without discipline.

Creating organization-based Identity in Auth0; the complexities that follow

Explore how what looks like simple Auth0 organization modeling reveals deeper architectural tradeoffs around isolation, token design, and authorization enforcement in tenant-first identity systems.

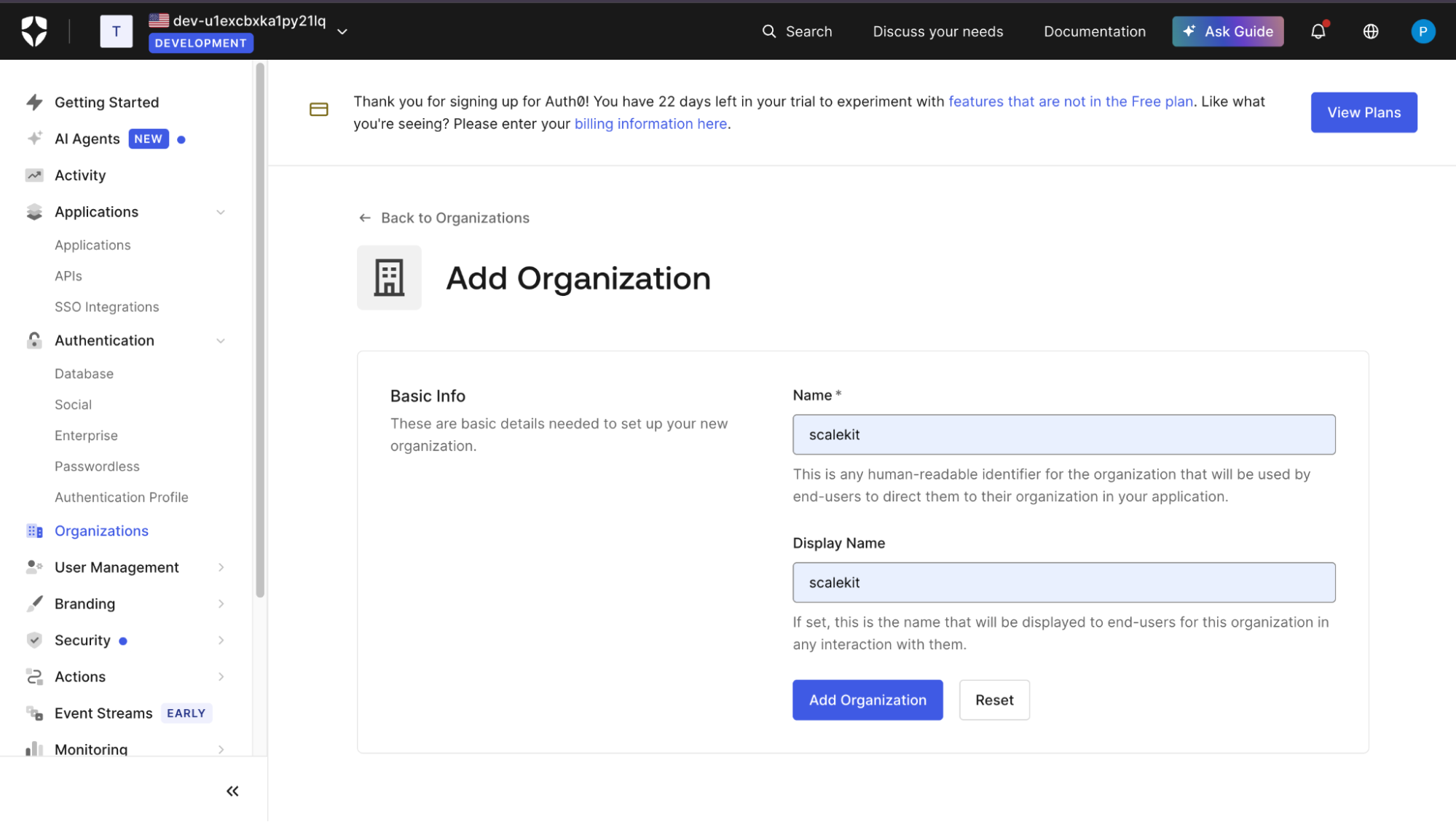

Step 1: Creating organizations and assigning users without breaking isolation

Creating organizations in Auth0 is operationally simple but architecturally subtle. Most teams first encounter with B2B modeling is when they create their initial organizations and start assigning users. The dashboard flow feels straightforward, which can hide how identity ownership is actually structured underneath.

This section walks through what you configure and what remains unchanged quietly.

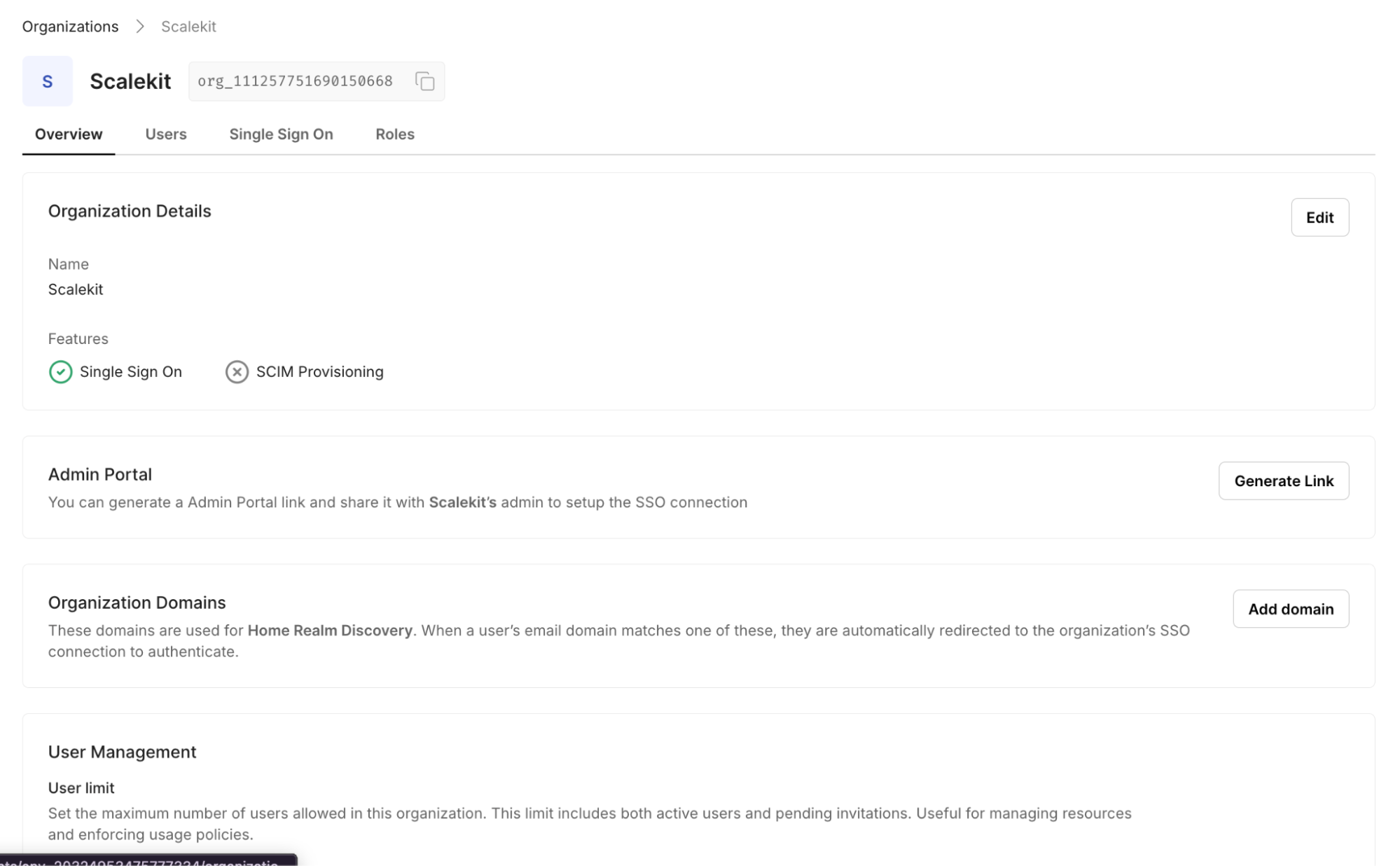

Creating an organization as a customer container

Organizations are created as logical groupings, not identity roots. In the Auth0 dashboard or via the Management API, an organization is created with a name, identifier, and optional branding. At this stage, no users are created, and no identities move.

The organization exists, but it has no independent authentication lifecycle. It cannot authenticate users on its own, and it does not store credentials.

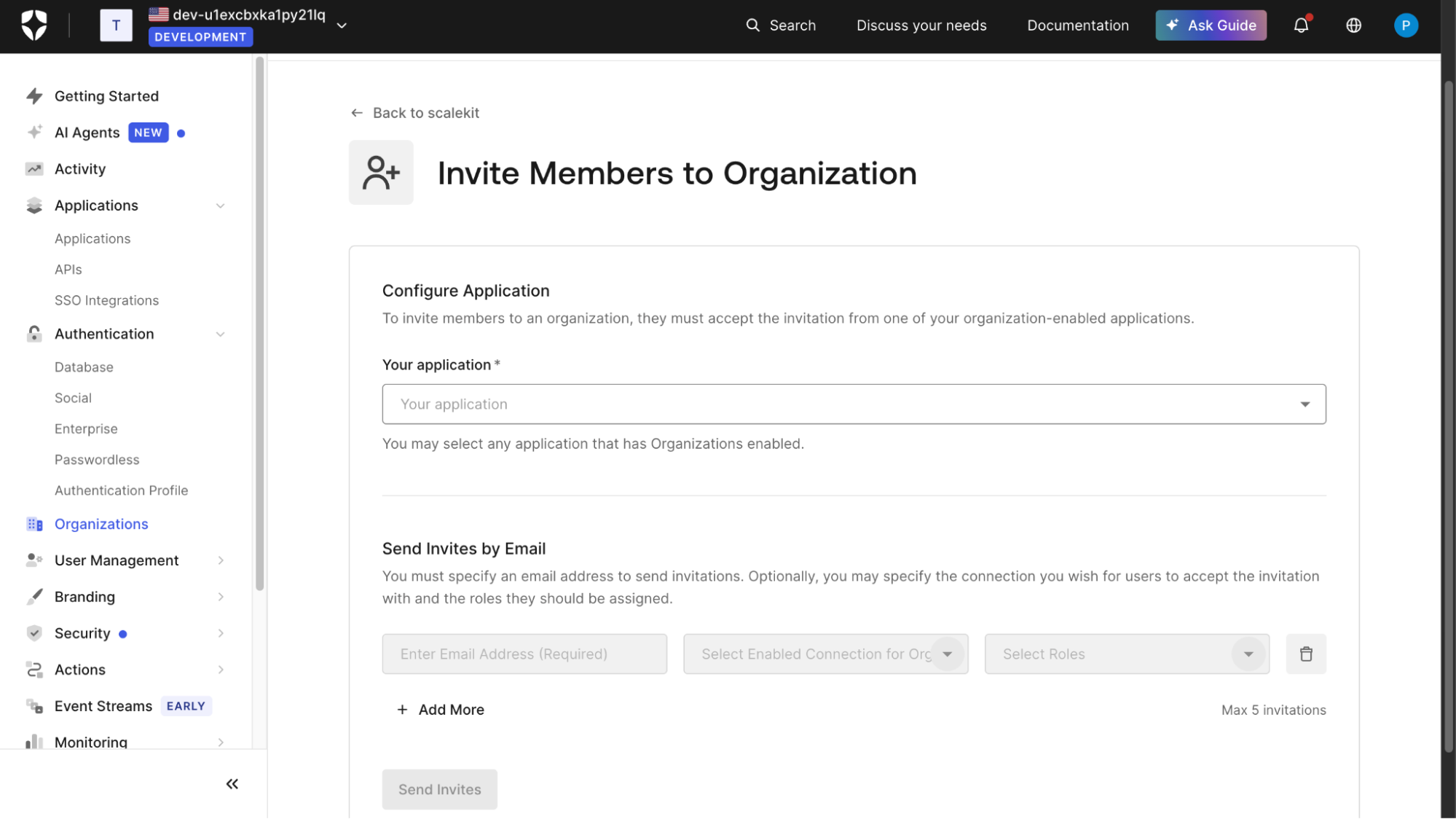

Adding existing users or inviting new members

Users are attached to organizations, not created inside them. When you add a member to an organization, Auth0 links an existing tenant-level user or sends an invitation that ultimately creates a tenant-level identity.

Key properties remain true:

- The user ID is global within the tenant

- The same user can join multiple organizations

- Removing a user from an org does not delete the identity

This separation is intentional but easy to overlook.

Assigning roles in an organization context

Roles are assigned at the org level but defined globally. Auth0 allows roles to be attached to users within an organization. This is the first place where authorization appears org-aware.

However:

- Roles are created once at the tenant level

- The same role can be reused across all orgs

- Role meaning must stay consistent everywhere

Any org-specific nuance must be enforced by convention or code.

Step 2: Making login flows explicitly organization-aware

Organization context is optional in Auth0 login flows unless you force it. This is the point where many B2B implementations begin to drift. Up to now, organizations and users coexist without conflict. During login, however, Auth0 will happily authenticate a user without knowing which organization they intend to operate in.

For B2B SaaS, that ambiguity is dangerous.

Passing the organization context during authorization

The application must declare organizational intent at login time. To make a login org-aware, the application must pass an organization parameter to the /authorize endpoint.

Example:

If this parameter is missing, Auth0 authenticates the user only at the tenant level. No error is thrown. No warning is emitted.

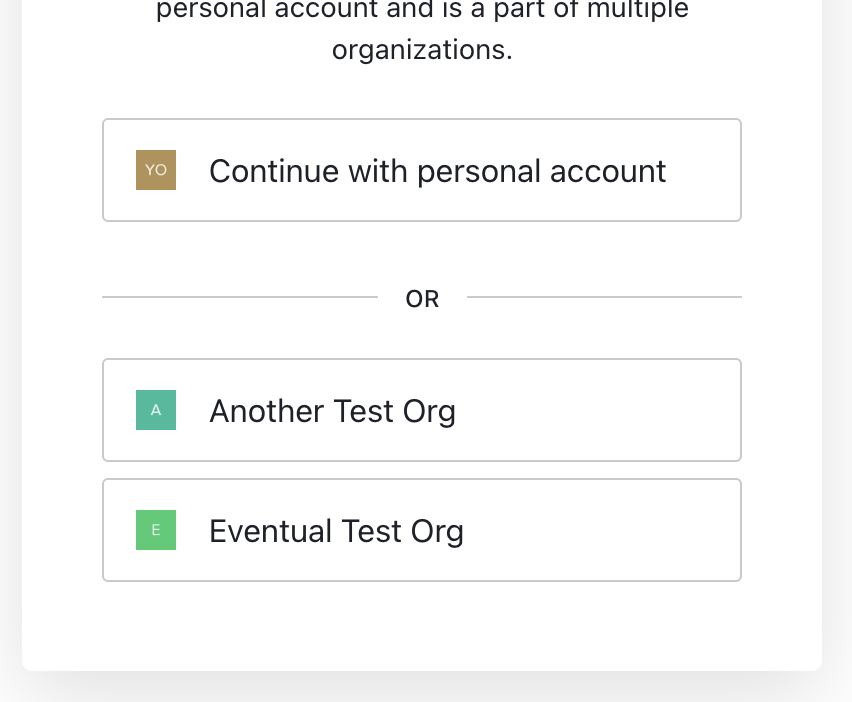

Handling users who belong to multiple organizations

Multi-org users require explicit context selection.

When a user belongs to more than one organization, the system must determine which org session to create. Auth0 does not enforce this decision automatically.

Typical approaches include:

- An org selection screen after login

- A deep link that encodes org context

- An application-side org switcher

Each approach requires custom logic and careful state handling.

Optional organization discovery via email domain

Org discovery reduces friction but adds coupling. Some teams map email domains to organizations and automatically infer org context. While this improves UX, it introduces hidden assumptions about ownership, mergers, and shared domains.

Auth0 supports this pattern, but correctness depends entirely on application-side rules.

Critical takeaway of this section

- Org context is not implicit

- Login can succeed without org awareness

- Your application must consistently supply and validate org intent

From this point forward, every missing org parameter becomes a latent authorization bug.

Step 3: Injecting organization context into tokens using Auth0 Actions

Tokens are not organization-aware unless you make them so. Even after an org-aware login, Auth0 does not automatically embed the organization context in ID or access tokens. Backend services cannot infer org membership unless that data is explicitly injected.

This is the point at which many teams first realize they are designing an identity schema.

Creating a Post-Login Action for token shaping

Auth0 Actions are the mechanism for persisting org context. A Post-Login Action runs after authentication and before tokens are issued. This is where organization identifiers and roles must be added as custom claims. By injecting org_id and roles into tokens, the Action ensures backend services can reason about organization boundaries without calling Auth0 again.

Minimal example:

This code looks simple, but it establishes long-term contracts.

What responsibility shifts to the application

Custom claims are entirely application-defined. Once org context lives in custom claims, Auth0 no longer enforces semantics. Your team must decide:

- Claim names and namespaces

- Which tokens include which claims

- Whether claims are always present

- How missing or stale org context is handled

Changing any of these later can break APIs, SDKs, and audits.

Making org context durable across services

Tokens become the single source of truth. Every backend service now depends on the correctness of these claims. If org context is missing, inconsistent, or overwritten, downstream authorization fails silently or dangerously.

This is no longer an authentication problem. It is an identity-data modeling problem.

Step 4: Enforcing organization-aware authorization across backend services

Authorization becomes a backend responsibility once the org context lives in tokens. After org identifiers and roles are embedded in tokens, every API must explicitly enforce access rules. Auth0 no longer participates in these decisions. The identity platform issues claims; your services interpret them.

This shift is subtle but permanent.

Reading organization context from tokens

Each request must be evaluated within an organization. Backend services typically extract the following from the access token:

- org_id (custom claim)

- roles (custom claim)

- sub (user identifier)

These values establish who is acting and which org they represent. If the org context does not match the resource being accessed, the request must be rejected.

There is no default enforcement layer. Every service must do this consistently.

Enforcing org isolation in application logic

Authorization checks must guard every data boundary. Most implementations follow a pattern similar to:

This logic appears simple, but it must exist:

- In every service

- On every protected route

- For every data access path

Any missed check becomes a multi-tenant vulnerability.

Handling users who switch organizations

In B2B systems, users often belong to multiple organizations. When they switch orgs, every request must be evaluated under a different security boundary.

In Auth0-based setups, organization context lives in tokens, and each token is scoped to a single org. The safest way to switch is to re-authenticate with a new organization parameter, so Auth0 issues a fresh, correctly scoped token. Some teams avoid this by issuing new tokens themselves, but that shifts identity guarantees into application code.

Reusing tokens across org switches is dangerous.

Requests may be authorized against the wrong organization, even when they appear valid, making these bugs hard to detect and audit.

Teams that stay safe usually enforce a few invariants:

- One active organization per session

- Token replacement on every org switch

- API clients reset with the new context

- Org context required on every backend request

Org switching is where tenant-first identity models begin to show strain, because organization context must be reconstructed rather than transitioned cleanly.

Dealing with duplication across services

Authorization logic spreads horizontally. Each backend service must:

- Parse tokens

- Validate org claims

- Enforce role semantics

- Produce org-aware logs

As systems grow, identity rules are copied, versioned, and occasionally diverge.

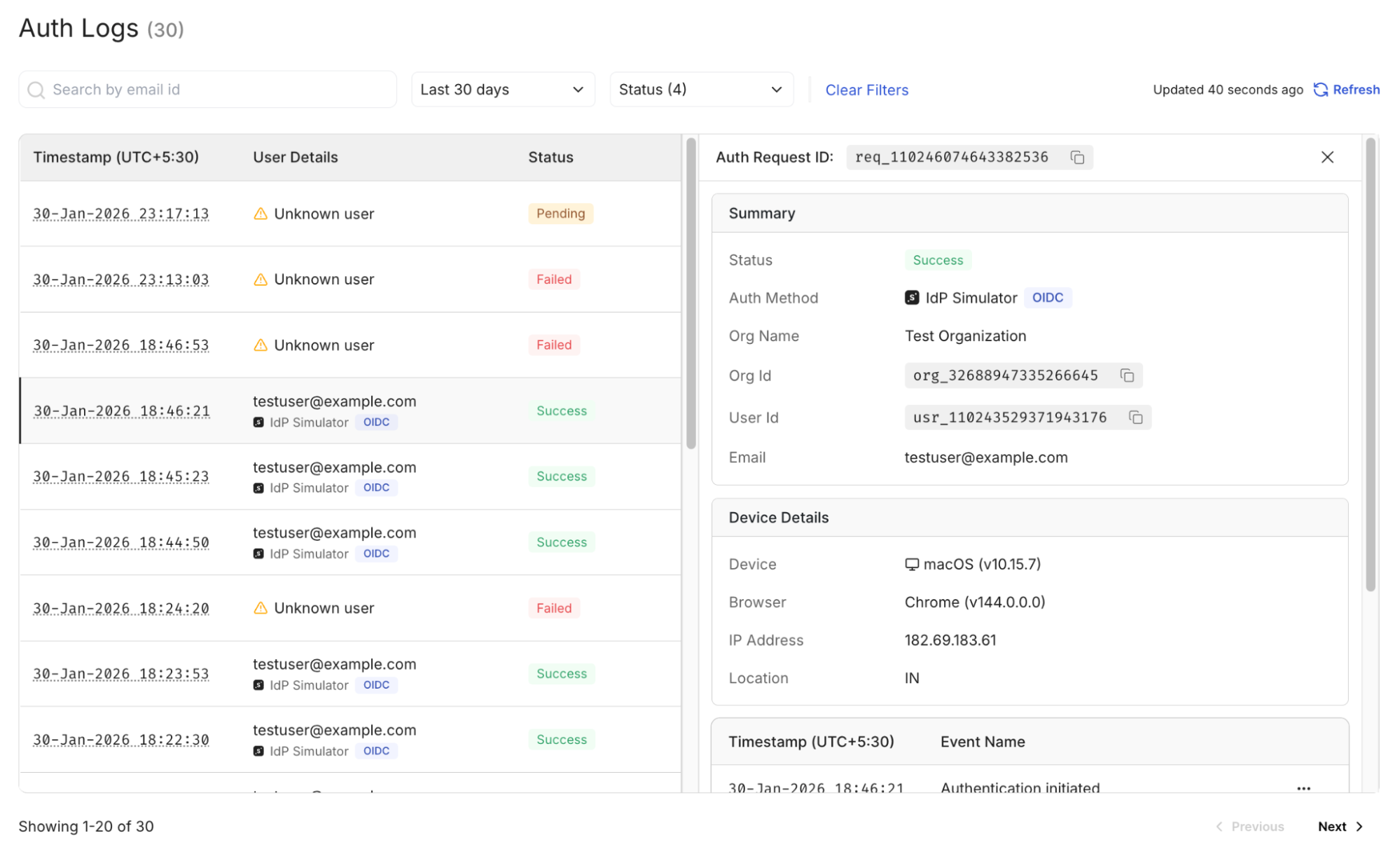

Step 5: Debugging, logging, and auditing with organization context

Operational visibility becomes harder when the organizational context is optional. After authentication and authorization are technically correct, teams encounter a different class of problems: support tickets, security reviews, and audits. These workflows depend on logs answering simple questions quickly.

In org-aware systems built on Auth0, those answers are not always obvious.

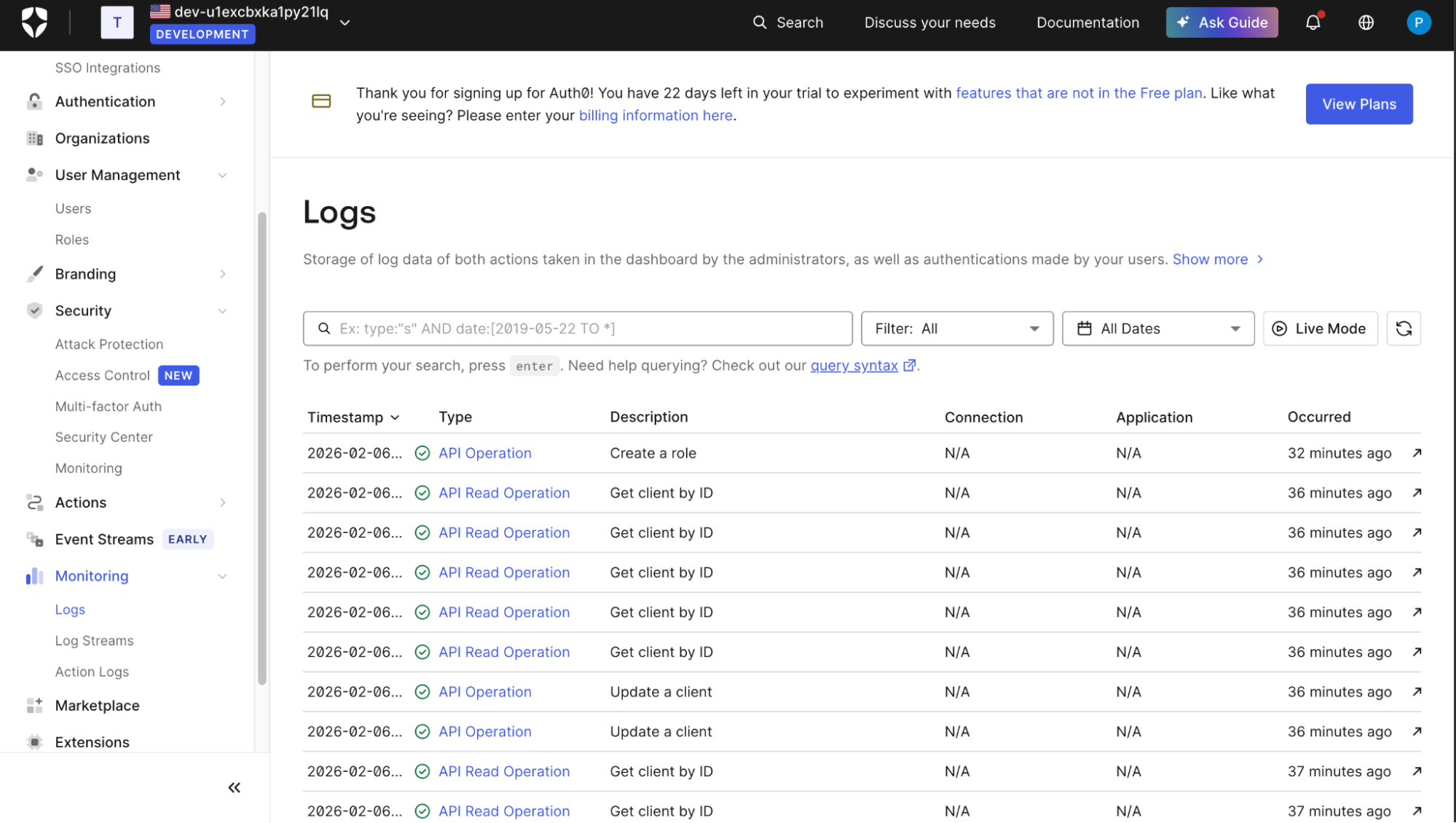

Inspecting authentication and authorization logs

Auth0 logs are tenant-scoped first, org-scoped second. The Auth0 Logs view provides detailed event data for logins, token issuance, and errors. However, organization context is not guaranteed to appear in every event.

Some login events include organization identifiers. Others do not, especially when the org context was not explicitly passed during authorization. This inconsistency matters during incident analysis.

Organization context in authentication logs

Org data depends on how the login was initiated. If a user authenticates without an organization parameter, the resulting logs reflect a tenant-level event. From the logs alone, it may be impossible to determine which customer context was intended.

At scale, this forces teams to correlate logs using custom claims, request metadata, or application-side identifiers.

Streaming logs for audits and compliance

Auditing requires external correlation. Many teams stream Auth0 logs into data warehouses to reconstruct org-level activity. This typically requires:

- Consistent claim naming

- Application-level log enrichment

- Cross-referencing user IDs with org mappings

None of this is enforced automatically. It relies on conventions staying intact over time.

How incremental fixes turn B2B authentication into a brittle system

B2B identity systems rarely fail all at once. Most Auth0-based setups reach a point where authentication, org-aware login, tokens, APIs, and logs technically work. From there, changes arrive incrementally, driven by enterprise deals, edge cases, or operational incidents rather than a planned identity redesign.

Each change is reasonable in isolation. The brittleness emerges from accumulation.

Actions become the default escape hatch

Post-Login Actions absorb complexity first. As requirements grow, teams add Actions to handle conditional roles, org-specific flags, feature access, or legacy behavior. Each Action solves a real problem, but Actions compose poorly.

Over time, identity logic spreads across multiple scripts with:

- Implicit ordering dependencies

- Shared assumptions about token shape

- Limited visibility into system-wide behavior

At this stage, correctness depends on knowing which Actions exist and how they interact.

Tokens slowly turn into a data transport layer

Tokens accumulate meaning beyond authentication. As new backend services are introduced, tokens are extended to include additional claims. Each new claim introduces a contract that downstream systems begin to rely on.

The risk compounds because:

- Claims are difficult to remove once adopted

- Consumers multiply faster than documentation

- Small changes ripple across services

Eventually, the token stops being a credential and starts behaving like an internal API payload.

Authorization logic spreads beyond backend services

Identity rules leak into more places. Authorization checks are now appearing not only in APIs but also in frontend applications, admin panels, and internal tooling. To manage this, teams build custom permission editors, org dashboards, and enforcement logic outside the core backend.

These tools often duplicate identity assumptions that already exist elsewhere, increasing the chance of drift.

Documentation becomes part of the system

Correct behavior depends on shared understanding. At this point, new engineers need onboarding documents to understand how orgs, roles, tokens, and Actions interact. The system still works, but correctness is enforced socially rather than structurally.

Documentation fills the gap left by missing platform guarantees.

Why is this brittleness hard to notice early

Each step feels incremental and justified. No single change breaks the system. The cost shows up later as slower onboarding, fragile audits, and fear around modifying identity code.

This is usually the moment teams realize that identity complexity has moved from configuration to application code.

How the same B2B setup looks when organizations are first-class in Scalekit

Scalekit approaches B2B SaaS authentication by making organizations the primary identity boundary. Instead of authenticating users into a global tenant and layering organization context later, Scalekit resolves identity directly within an organization. Users, roles, sessions, and logs are all evaluated in that context by default.

This changes where complexity lives and where it doesn’t. The flowchart below shows how Scalekit’s org-first model resolves identity, roles, sessions, and tokens without later injecting organization context.

Creating organizations as first-class identity boundaries

Organizations are the starting point in Scalekit, not an overlay. When you create an organization in Scalekit, you are creating a security boundary that owns its members, roles, sessions, and policies.

Key differences from Auth0:

- Organizations are not layered on top of users

- Identity resolution always happens within an org

- There is no concept of a tenant-only session

This eliminates an entire class of “missing org context” failures.

Defining roles scoped to an organization

Roles are scoped natively per organization. In Scalekit, roles are defined inside an org and have no meaning outside it. An “admin” role in one organization does not exist in another unless explicitly created.

This removes the need for:

- Global role naming conventions

- Per-org role interpretation logic

- Defensive checks against role reuse

Authorization semantics are enforced structurally.

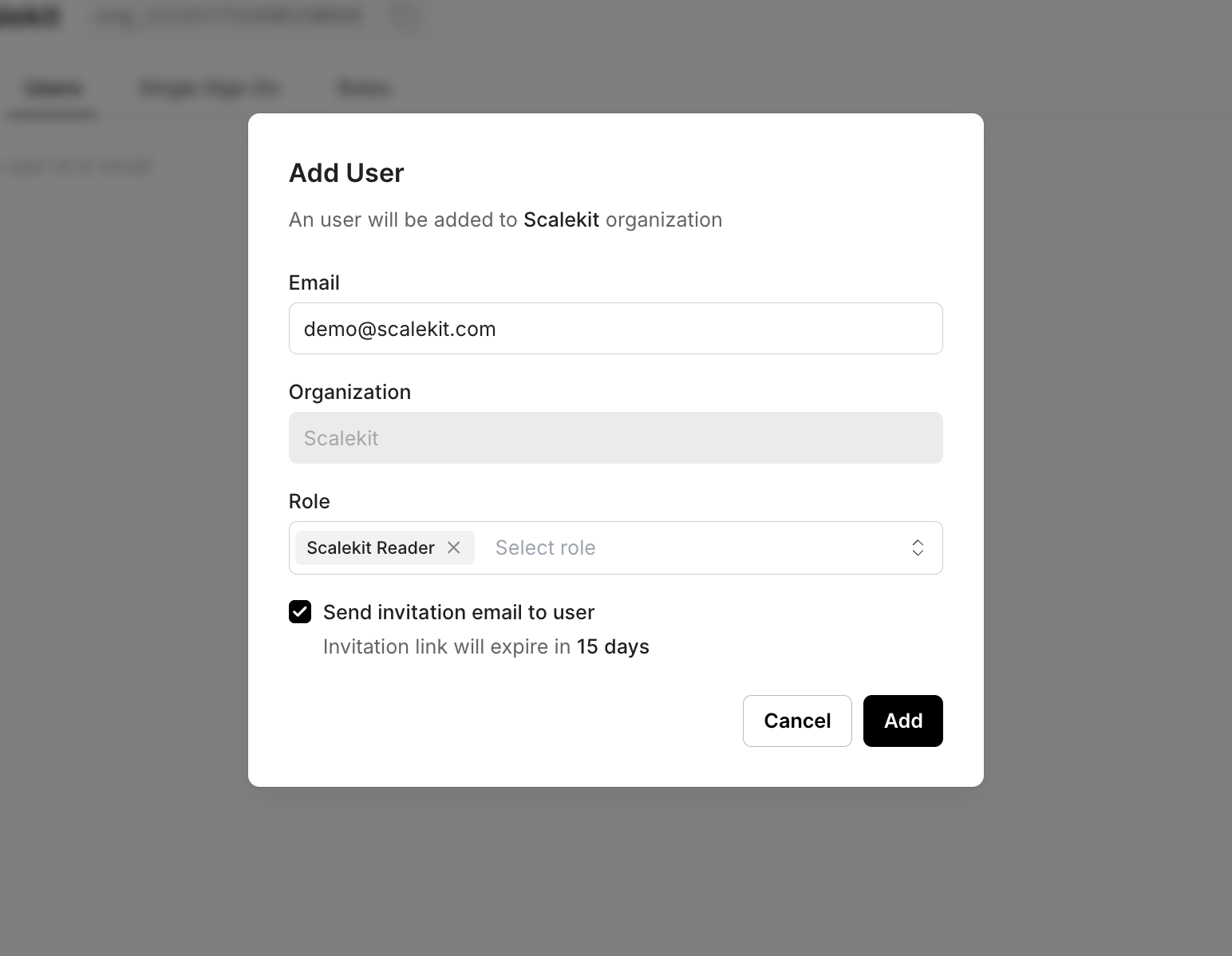

Inviting users and supporting multi-org membership

Users join organizations, not tenants. Scalekit supports users belonging to multiple organizations, but membership is explicit, and context is always resolved at session start.

Important behavioral differences:

- A session always belongs to one organization

- Switching orgs always results in a new session

- Tokens are never reused across org contexts

This makes org switching a state transition, not a reconstruction problem.

Tokens and sessions are always org-aware

Organization context is inherent, not injected. Tokens and sessions issued by Scalekit include organization identifiers as first-class fields, not custom claims added via scripts.

As a result:

- No Post-Login Actions are required

- Backend services do not need to infer org context

- Token shape is platform-owned and stable

Identity semantics remain centralized.

Logging and audits remain aligned by default

Logs are org-scoped end-to-end. Authentication events, session creation, and access decisions are all emitted with organization context by default.

This removes the need for:

- Log correlation heuristics

- Custom enrichment pipelines

- Reconstructing org context during audits

Operational visibility stays consistent as the system grows.

“The difference between these approaches is not capability, but how much identity correctness the application is expected to maintain over time.”

Deciding when to stay with Auth0 and when to switch platforms

The decision is not about features. It is about where identity complexity should live.

Both Auth0 and Scalekit can support B2B SaaS. The difference lies in who is responsible for ensuring B2B behavior is correct as requirements evolve.

A useful way to think about this choice is to ask:

Is identity still a supporting concern, or has it become a core part of the product’s correctness?

Practical decision boundaries

How to interpret these boundaries

Auth0 works best when identity is adaptable. Auth0 provides strong primitives and flexibility. That flexibility is valuable when requirements are still changing, customers are homogeneous, and the team is comfortable assembling and maintaining B2B semantics in application code.

Scalekit works best when identity correctness must be structural. Scalekit trades flexibility for opinionated guarantees. Organization context, role scoping, sessions, and logs are enforced at the platform boundary rather than reconstructed later. This matters when identity errors translate directly into customer trust, audit risk, or operational drag.

Conclusion

B2B SaaS authentication is not primarily a login problem. It is an organizational boundary problem that affects authorization, auditing, and the long-term correctness of the system. As soon as a product serves multiple customer organizations, identity stops being global and becomes contextual. Every request must be evaluated not just by who the user is, but also by which organization they are acting on behalf of and what that organization allows them to do.

Auth0 can support B2B SaaS by providing flexible primitives for organizations, roles, Actions, and extensible tokens. That flexibility is valuable early on, but it also means the application must actively assemble and maintain B2B semantics over time. Org context, token structure, authorization rules, and auditability increasingly live in application code, where small inconsistencies can quietly compound into operational risk.

Org-first identity platforms like Scalekit take a different approach. By enforcing organization context, role scoping, sessions, and logs as first-class platform guarantees, they reduce the amount of identity logic applications must carry forward. The right choice is not about features, but about ownership: deciding whether identity correctness should be maintained by convention in your codebase or enforced structurally by the platform as your B2B product scales.

FAQs

Why does B2B authentication feel harder than consumer authentication?

Because B2B authentication is fundamentally about enforcing organizational boundaries, not just verifying users. Every request must be evaluated in the context of an organization, and that context must remain consistent across login flows, tokens, backend services, and audits. Small inconsistencies can quietly turn into multi-tenant security risks.

Is multi-tenancy mainly a data problem or an identity problem?

It is both, but identity is where multi-tenancy errors become most dangerous. Data models can enforce isolation at rest, but identity systems determine which tenant a request is evaluated against. If the organizational context is missing, optional, or reconstructed inconsistently, even well-designed data models can be bypassed.

Why do organization-related bugs tend to surface late?

Because authentication usually succeeds even when the organization context is incorrect. Users can log in, requests return data, and permissions appear to work. Issues often surface only during audits, customer escalations, or security reviews, when teams need to explain which organization a user was acting on behalf of and why an action was allowed.

How should teams think about choosing an identity platform for B2B SaaS?

A useful framing is to ask where identity complexity should live over time. General-purpose platforms offer flexibility and strong primitives, which work well early on. Org-first platforms like Scalekit trade some flexibility for structural guarantees that enforce organizational context, role scoping, and session boundaries at the platform level.

Does an org-first identity model limit application flexibility?

It constrains certain configuration patterns, but those constraints are intentional. By making organization context mandatory and native, org-first systems reduce the need for defensive checks, token shaping, and reconstruction logic in application code. The trade-off is fewer escape hatches in exchange for more predictable behavior.

When do teams usually consider moving to an org-first approach?

Teams often reach this point when organization context appears in nearly every request, multiple services must agree on authorization behavior, and audits or customer trust depend on strict isolation. At that stage, identity correctness has become infrastructure rather than integration.

Is adopting an org-first identity model a permanent decision?

No. Many teams start with flexible identity systems, learn where B2B complexity accumulates, and later decide whether that complexity belongs in application code or in the identity platform. The important step is recognizing when that transition point has been reached.

.png)