Understanding JSON Web Tokens: Complete guide for developers

TL;DR

- JWTs are not an authentication system. They are a standardized, signed token format used to carry verified claims after authentication has already occurred, most commonly via OAuth 2.0 or OpenID Connect.

- JWTs enable scalable, stateless request validation across distributed systems. Their self-contained nature allows APIs and microservices to validate requests independently, without shared session storage.

- JWT security depends on strict validation and lifecycle controls. Signature verification alone is insufficient; services must enforce issuer, audience, expiration checks, algorithm allow-lists, and key rotation.

- Short-lived access tokens and proper key rotation are essential. Stateless JWTs are difficult to revoke in real time, so production systems rely on short expirations, refresh flows, and JWKS-based key management.

- JWTs are powerful when used in the right context, and risky when misused. They work best as access and identity tokens within OAuth/OIDC architectures, but are not ideal for applications requiring immediate revocation or heavy server-side session control.

JSON Web Tokens (JWT) as a building block for distributed systems

In large organizations, authentication rarely happens in a single place. A user may sign in through a centralized identity provider, access multiple internal tools, call partner APIs, and interact with several backend services within a single session. Passing identity and authorization context reliably across these boundaries is a core enterprise requirement, and JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are commonly used for this.

JWTs are often misunderstood as an authentication mechanism, but they are not an authentication system. A JWT is a standardized, signed token format for encoding claims that other systems can verify. In enterprise setups, JWTs are typically issued by an authorization or identity system, most commonly through OAuth 2.0 or OpenID Connect (OIDC), after a user or service has already been authenticated.

Because JWTs are compact, self-contained, and cryptographically verifiable, they work well in microservice architectures, internal APIs, and zero-trust environments. Each service can validate tokens independently without shared session state, which simplifies scaling but introduces new responsibilities around token lifetimes, validation, and key rotation. This guide focuses on how JWTs fit into that broader system and how to use them safely in production.

What is JWT?

A JSON Web Token (JWT) is a compact, URL-safe token format used to transmit claims between parties in a verifiable way. At its core, a JWT is a JSON object that has been cryptographically signed, allowing the recipient to validate that the data has not been altered and to trust the issuer of the token. JWTs are signed using either a shared secret (HMAC) or an asymmetric key pair (RSA or ECDSA).

It’s important to be precise about what JWTs do. A JWT does not authenticate a user or grant access on its own. Instead, it carries claims, such as who the subject is, who issued the token, and who it is intended for, that other systems can evaluate. Authentication and authorization decisions are made by the systems that issue and validate JWTs, not by the token format itself.

JWTs are commonly used in authentication and authorization systems because they are easy to transmit and verify across service boundaries. They are typically sent in HTTP headers as bearer tokens, though they can also be transmitted via cookies depending on the application architecture. Their compact size and standardized structure make them a practical choice for APIs, service-to-service communication, and distributed systems.

In identity systems, JWTs are widely used as the token format for OAuth 2.0 access tokens and OpenID Connect (OIDC) ID tokens. In these flows, the JWT represents the outcome of an authentication event or an authorization grant; it does not perform either function on its own.

Stateless JWTs and what “Stateless” really means

JWTs are often associated with stateless architectures, but statelessness is a system design decision, not an inherent property of the token. In a stateless setup, all the information needed to validate a request is contained within the token itself, allowing services to verify requests without consulting shared session storage.

This approach can reduce coupling between services and simplify horizontal scaling, which is why it is popular in microservice and API-driven environments. However, stateless JWTs also introduce tradeoffs. Because tokens are self-contained, revoking them immediately is difficult unless additional state, such as revocation lists or token introspection, is introduced.

For this reason, many production systems combine JWTs with short-lived tokens and key rotation to balance scalability with security and control.

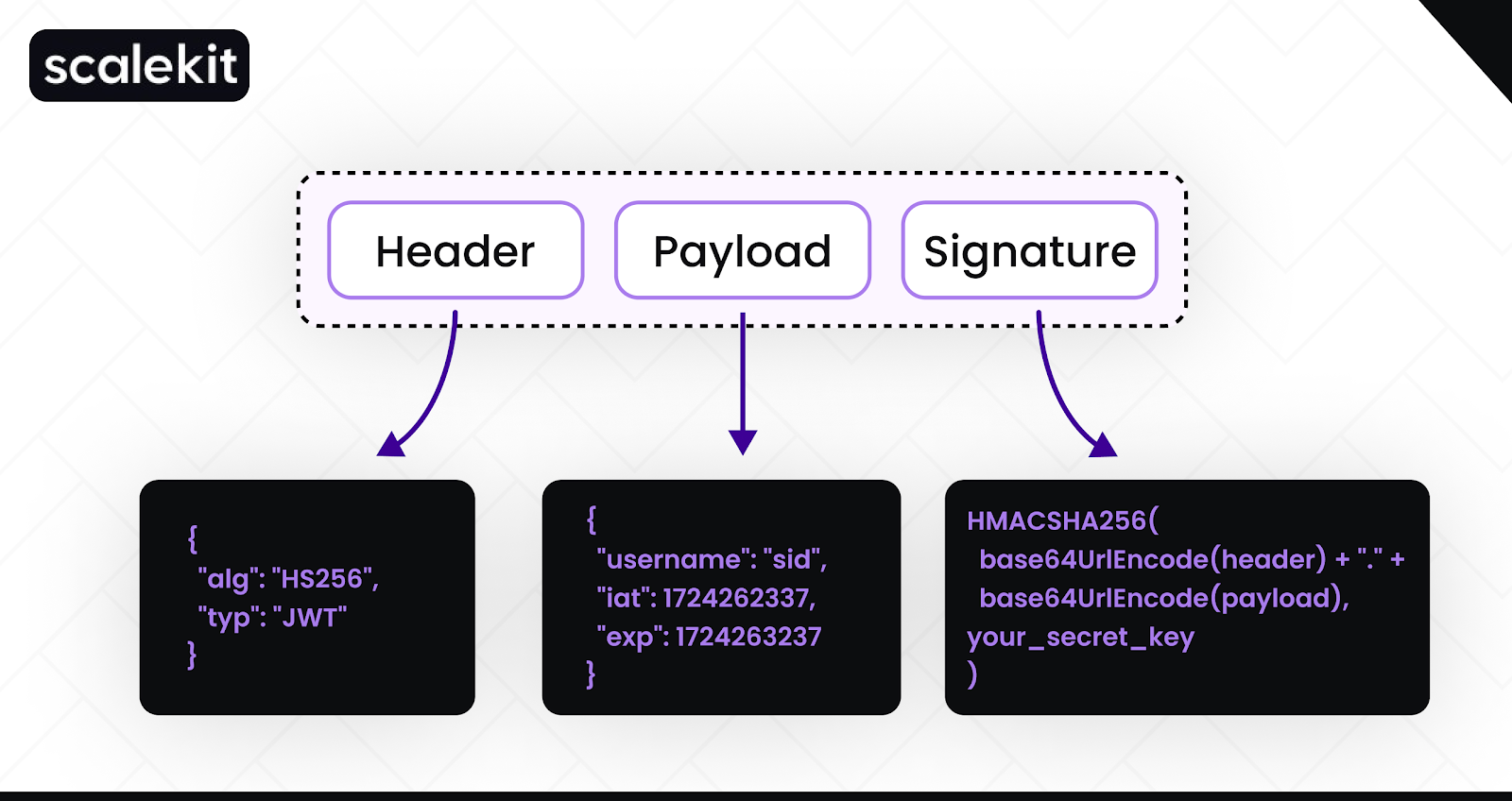

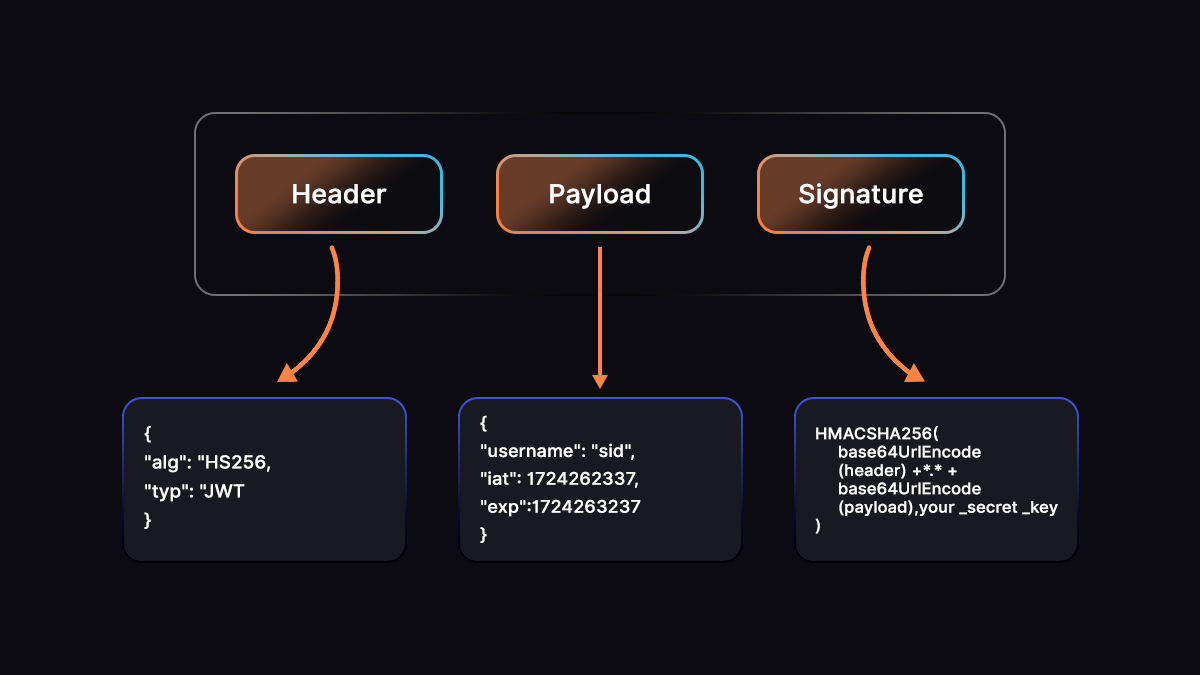

Structure of a JSON Web Token

A JWT consists of three parts, each Base64URL-encoded and separated by dots. Base64URL is a URL-safe variant of Base64 that replaces the + and / characters with - and _, and omits padding characters (=). This ensures JWTs can be safely transmitted in URLs and HTTP headers without additional encoding.

- Header: The header specifies the token type and the signing algorithm used, such as HS256 or RS256. This information tells the verifier how to validate the token.

- Payload: The payload contains claims, statements about the subject, the issuer, and the token’s intended use. Claims can be registered (such as iss, aud, and exp), public, or private. The payload is not encrypted by default, which means it should never contain sensitive data.

- Signature: The signature is generated using the encoded header, encoded payload, and a signing key. It allows the recipient to verify the token’s integrity and confirm that it was issued by a trusted authority. If the signature is invalid, the token must be rejected.

Together, these three components enable JWTs to be efficiently transmitted and independently verified, but only when used as part of a correctly designed authentication and authorization system.

Key factors for secure JWT implementation

A JWT’s security does not come from its structure alone; it depends on how rigorously the token is issued, validated, and managed throughout its lifecycle. Even though a JWT is cryptographically signed, it is only trustworthy if the receiving system enforces strict validation rules. Choices such as which signing algorithms are allowed, how signing keys are managed, and which claims are required all directly affect whether a JWT implementation is secure in practice.

At minimum, services validating JWTs should verify the token’s signature using trusted keys and explicitly check critical claims such as issuer (iss), audience (aud), and expiration (exp). Relying on signature verification alone is a common mistake. Tokens must also be rejected if they use unexpected algorithms, reference unknown key IDs (kid), or violate time-based constraints. These checks ensure the token was issued by the correct authority, intended for the receiving service, and is still valid.

Key management is equally important. Signing keys should be rotated regularly, algorithms should be allow-listed rather than accepted dynamically, and tokens should be issued with short lifetimes to limit blast radius if compromised. JWTs are powerful, but only when used as part of a controlled system rather than as a self-contained security solution.

Example of a JSON Web Token

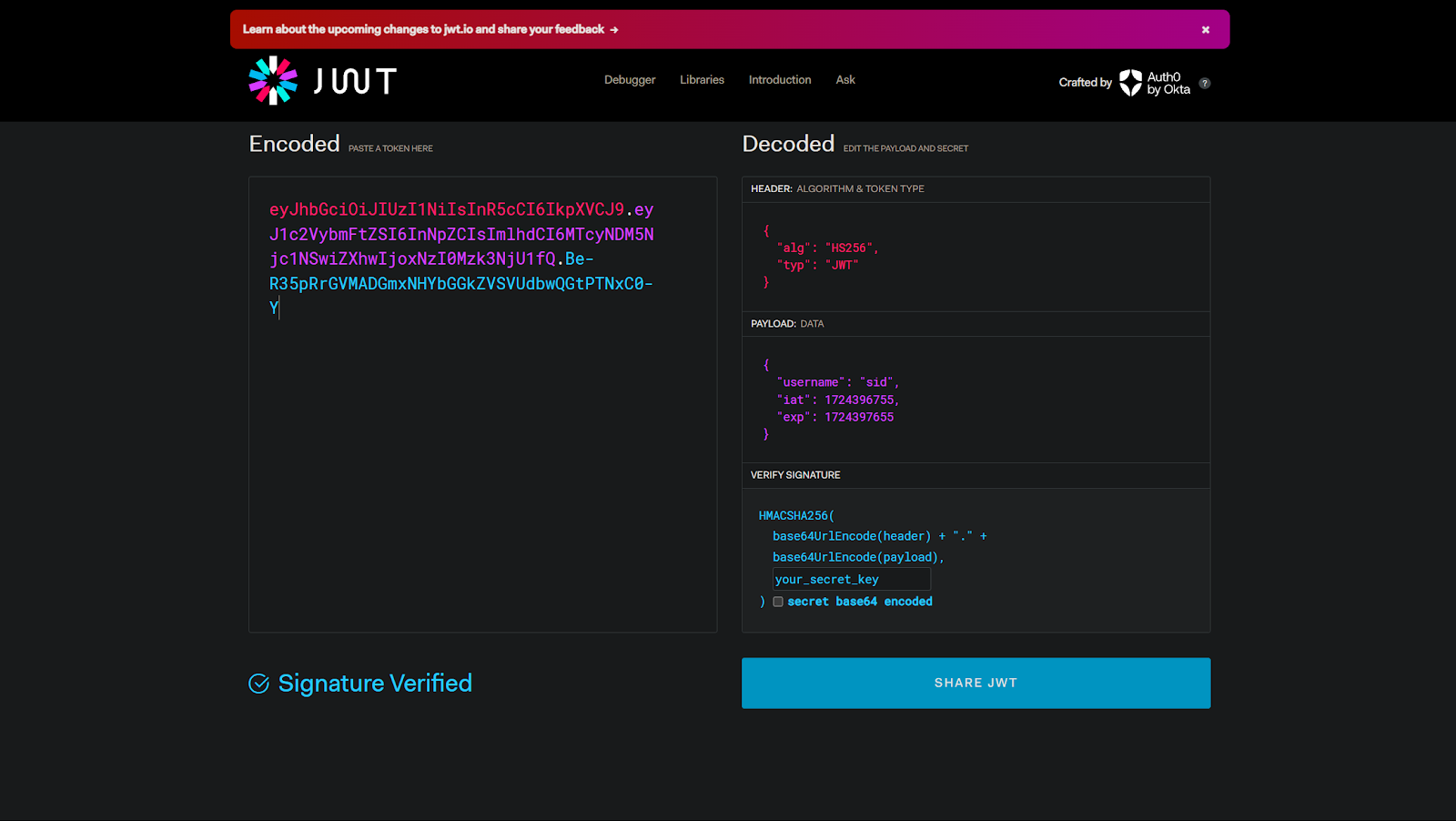

A JWT is transmitted as a single string made up of three Base64URL-encoded parts separated by dots. This encoded form is what clients send to APIs and services on each request.

Although this representation looks opaque, it is only encoded, not encrypted. Anyone with access to the token can decode its contents.

Decoded JWT header

The header describes how the token was created and how it should be verified.

- alg specifies the signing algorithm used to generate the signature

- typ indicates the token type

Systems validating JWTs should never blindly trust these values. Allowed algorithms must be explicitly configured on the server.

Critical security note for developers:

Never accept the none algorithm ("alg": "none"). This is a known class of vulnerabilities where attackers can craft unsigned tokens that bypass verification if the server does not enforce algorithm checks. Always configure an explicit allowlist of accepted algorithms (for example, RS256 or ES256) and reject any tokens that use none or unexpected algorithms.

This ensures that token verification behavior is deterministic and resistant to algorithm-confusion and downgrade attacks.

Decoded JWT payload (Claims)

The payload contains claims about the subject and the context in which the token was issued.

Claims are fully readable once decoded. For this reason, sensitive information should never be placed in the payload. Fields such as sub (subject) and iat (issued at) are commonly used, but their presence alone does not grant access; authorization decisions must be enforced separately by the receiving service.

Developer note:

Time-based claims such as iat (issued at) and exp (expiration time) are NumericDate values as defined in RFC 7519. They represent Unix timestamps in seconds, not milliseconds. In the example above, 1516239022 corresponds to seconds since the Unix epoch.

This distinction matters in practice, as misinterpreting timestamps can lead to tokens being treated as valid for far longer, or shorter, than intended.

Signature and verification

The final part of the JWT is the signature. It is generated using the encoded header, encoded payload, and a signing key.

When a service receives a JWT, it verifies the signature using a trusted key, such as a shared secret or a public key obtained from a JWKS. If the signature does not validate, or if required claims are missing or invalid, the token must be rejected.

Signature verification is what makes a JWT trustworthy. Without strict verification and claim validation, a decoded token is just untrusted data.

How JWTs are issued and used in authentication flows

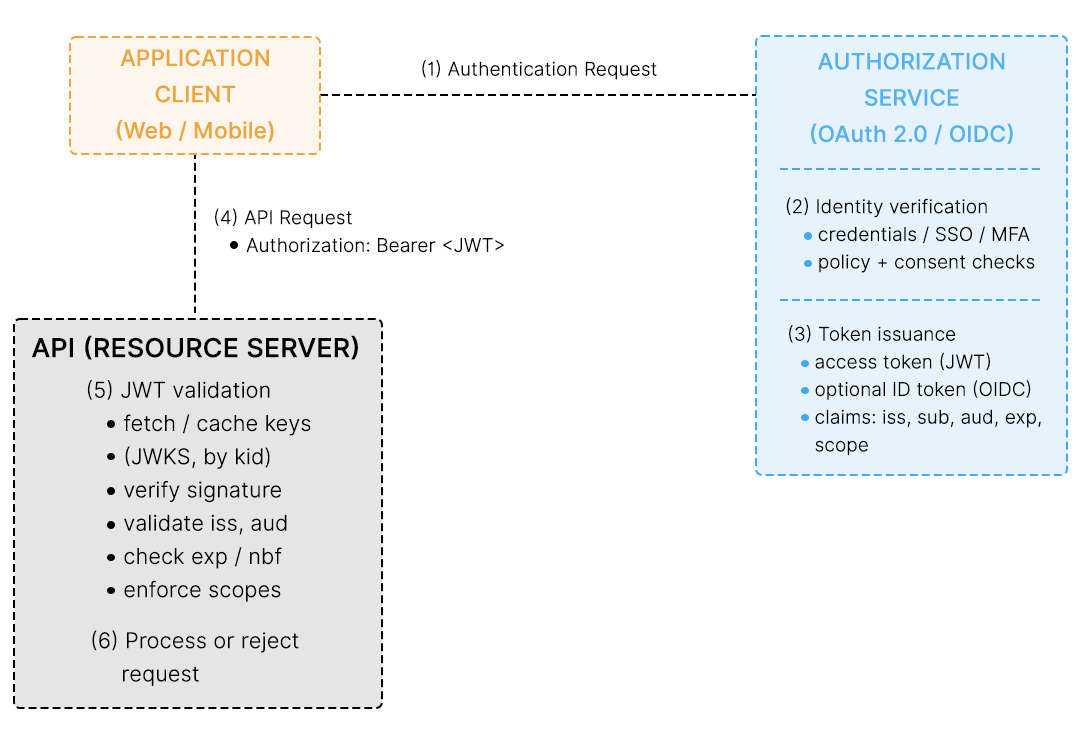

JWTs are not responsible for authenticating users. Instead, they are issued after authentication has already happened, typically by an authorization server or identity provider. In enterprise systems, this flow is most commonly implemented using OAuth 2.0 or OpenID Connect.

When a user signs in, the client application sends an authentication request to the authorization server. The authorization server validates the user’s credentials using its own mechanisms, such as passwords, SSO, or MFA. If authentication succeeds, the authorization server issues a token, often a JWT, back to the client. This token represents the result of that authentication and authorization decision.

The client then includes this JWT in subsequent requests to APIs or backend services, usually in the Authorization: Bearer header or via a secure cookie. The API does not re-authenticate the user. Instead, it validates the token, checks its claims, and decides whether to allow the request.

What happens during JWT validation

When an API (also called a resource server) receives a request with a JWT, it must treat the token as untrusted input until verification succeeds. Validation involves more than just checking whether the token exists.

At a minimum, the API should:

- Verify the token’s cryptographic signature using a trusted key to ensure it has not been tampered with.

- Confirm the token was issued by the expected issuer (iss) so the API only trusts tokens from known authorities.

- Ensure the token was intended for this API (aud) to prevent tokens issued for other services from being reused.

- Check time based validity constraints, including:

- exp (expiration time), which defines when the token must no longer be accepted.

- nbf (not before), a NumericDate timestamp that specifies the earliest time at which the token is valid and must not be accepted before that moment.

If any of these checks fail, the request must be rejected. A valid signature alone is not sufficient. JWT security depends on strict claim validation and explicit trust boundaries.

Signing keys and trust boundaries

JWT signatures enable systems to trust tokens without shared session state. That trust depends entirely on how signing keys are managed.

With symmetric signing (HMAC), the same secret is used to sign and verify tokens. This approach is simple but risky at scale, because every system that verifies tokens must also be trusted to protect the signing secret. If the secret leaks, attackers can mint valid tokens.

With asymmetric signing (RSA or ECDSA), the authorization server signs tokens using a private key, while APIs verify them using a public key. This model is better suited for enterprise and multi-service environments because only the issuer can create tokens, while many services can safely verify them.

Regardless of the algorithm, signing keys must be rotated regularly and distributed securely, often via JWKS endpoints. Weak key management undermines the entire security model, even if the JWT format itself is used correctly.

Important note on token storage

JWTs are commonly sent in authorization headers, especially for APIs and service-to-service calls. In browser-based applications, they may also be stored in HTTP-only, secure cookies to reduce exposure to XSS attacks. Storage strategy depends on the client type and threat model, but no storage option is “safe by default” without proper controls.

JSON Web Key Sets (JWKS)

In production systems, signing keys should be rotated regularly, and multiple keys may be active simultaneously. JSON Web Key Sets (JWKS) provide a standardized way for token issuers to publish the public keys clients and APIs need to verify JWT signatures. A JWKS is a JSON document that contains one or more cryptographic keys, each identified by a key ID (kid).

Rather than hard-coding verification keys, resource servers fetch the JWKS from a trusted endpoint exposed by the authorization server. When a JWT is received, the verifier uses the kid value in the token header to select the correct key from the set. This design allows new keys to be introduced and old keys to be retired without downtime or coordinated redeployments across services.

A simplified JWKS might look like this:

- The kid field uniquely identifies each key and allows verifiers to select the correct key for a given token.

- The use field indicates the intended purpose of the key. A value of sig means the key is intended for signature verification, while a value of enc would indicate a key used for encryption, such as in JSON Web Encryption (JWE) scenarios.

Each entry represents a public key that can verify token signatures. The presence of multiple keys enables seamless key rotation: new tokens are signed with a new key, while previously issued tokens remain verifiable until they expire.

JWTs as access tokens

In OAuth 2.0-based systems, JWTs are commonly used as access tokens. An access token represents the authorization granted to a client, not the user’s authentication state. It tells a resource server what the client is allowed to do, not how the user logged in.

JWT access tokens typically include claims such as the intended audience (aud), scopes or permissions, and an expiration (exp). When an API receives a request, it validates the token and evaluates these claims to decide whether the requested operation is allowed. The API does not rely solely on the token format; authorization is enforced by mapping token claims to application-specific access rules.

Using JWTs as access tokens enables APIs to make authorization decisions locally and consistently, provided signature verification, claim validation, and key rotation are handled correctly.

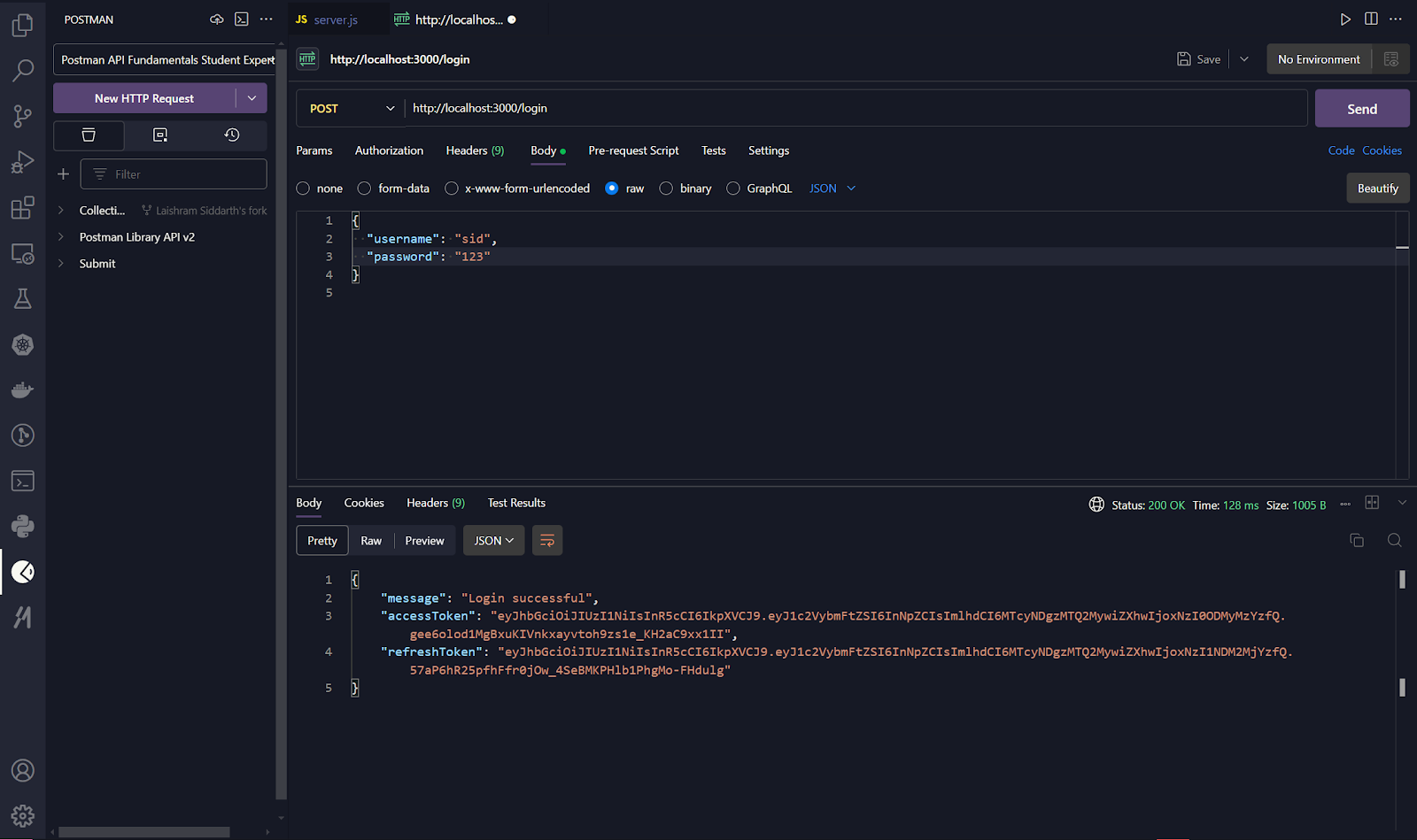

Implementing JWT: A practical guide with Node.js

This walkthrough demonstrates how JWTs are issued and validated inside a backend API. The example focuses on token handling and request validation rather than implementing a full OAuth or identity provider. In real-world deployments, token issuance is typically handled by a dedicated authorization service, while APIs validate tokens and enforce access rules.

The goal here is to show how JWTs are used correctly in practice and to highlight the checks that matter in production systems.

1. Project setup

Start by initializing a basic Node.js project and installing the required dependencies:

These dependencies serve distinct roles in the example:

- Express is used to define API routes and middleware for handling HTTP requests.

- jsonwebtoken provides utilities for signing and verifying JWTs.

- bcryptjs allows secure verification of user credentials during login.

- cookie-parser enables the API to read HTTP-only cookies when tokens are transmitted via cookies.

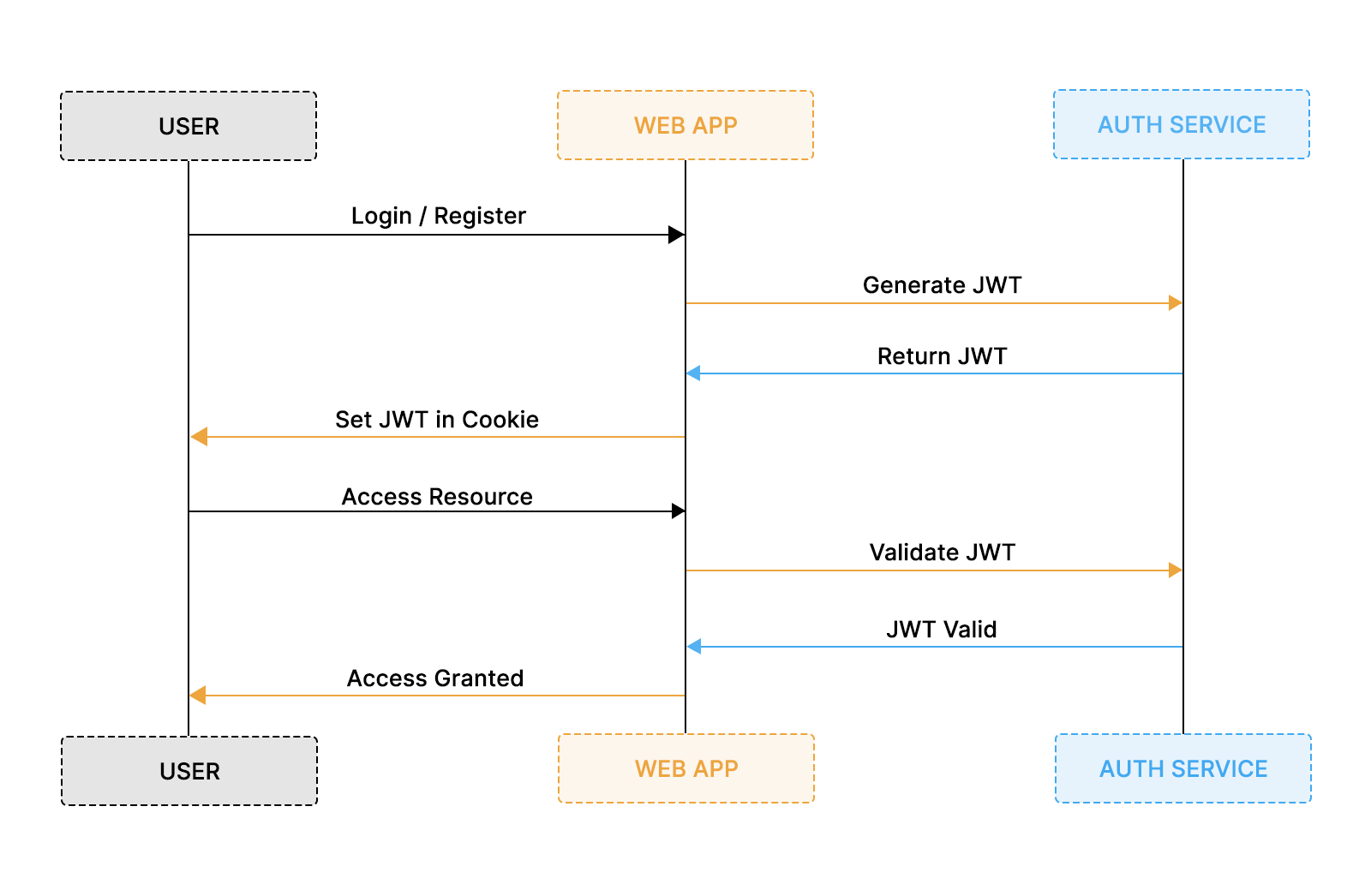

2. Issuing JWTs after login

In this simplified setup, the API verifies user credentials and issues a JWT upon successful authentication. While this responsibility often belongs to an authorization server in larger systems, keeping it in one place here makes the token lifecycle easier to follow.

What’s happening during login:

- The server verifies the user’s credentials by comparing the password to a hash.

- A short-lived JWT is issued only after authentication succeeds.

- Standard claims such as sub, iss, and aud are included so downstream services can validate context.

- The token is returned via an HTTP-only, secure cookie, reducing exposure to client-side attacks.

The key takeaway is that the JWT represents the result of authentication rather than performing authentication itself.

3. Validating JWTs on protected routes

When a client accesses a protected endpoint, the API does not re-authenticate the user. Instead, it validates the JWT attached to the request and decides whether to proceed.

During token validation, the API enforces several critical checks:

- The token’s signature is verified using a trusted public key.

- The issuer and audience claims are validated to ensure the token was meant for this API.

- Time-based constraints, such as expiration, are enforced to prevent reuse of stale tokens.

Only after these checks pass does the API process the request. Skipping any of these validations can allow forged or replayed tokens to be accepted.

4. Refreshing access tokens safely

Access tokens are intentionally short-lived to limit the damage if they are leaked. To maintain user sessions without forcing repeated logins, applications rely on refresh tokens to obtain new access tokens when their existing ones expire. Refresh tokens should be treated as long-lived credentials and handled more carefully than access tokens.

Below is a simplified refresh flow that demonstrates the mechanics without introducing unsafe shortcuts.

Refresh token endpoint

What’s happening in this flow

- The client sends a refresh request without re-submitting credentials.

- The API verifies the refresh token using a trusted key and strict claim checks.

- A new short-lived access token is issued if validation succeeds.

- The refreshed access token replaces the expired one transparently.

In production systems, refresh tokens should be rotated on every use and stored server-side so that replayed tokens can be detected and rejected. This example keeps refresh handling minimal to avoid obscuring the core mechanics.

5. Verifying JWTs explicitly

Token verification is the most security-critical step in any JWT-based system. APIs must treat every incoming token as untrusted input until all verification and claim checks pass. Relying on default library behavior or skipping explicit validations is a common source of vulnerabilities, especially as systems evolve, teams change, or multiple identity providers are introduced.

Centralized token verification helper

This helper enforces a consistent validation policy across the application. Restricting allowed algorithms prevents downgrade and confusion attacks, while issuer and audience checks ensure that only tokens issued by a trusted authority and intended for this API are accepted.

Using verification in middleware

By verifying tokens inside middleware, invalid requests are rejected before they reach application logic, and downstream handlers only ever see a validated identity context.

Why centralized token verification works

- Centralizing verification logic ensures that all routes apply the same cryptographic and claim-level checks.

- Invalid, expired, or tampered tokens are rejected early, reducing the risk of accidental authorization bypass.

- Business logic remains clean and focused, since it never needs to handle raw or unverified tokens.

- Validation behavior becomes predictable, testable, and easier to audit over time.

Verifying tokens during development

During development and debugging, tools such as JWT.io are useful for inspecting tokens outside the application. By pasting a JWT into the tool, you can decode the header and payload, confirm which claims are present, and verify that the signature matches the expected key. This is helpful for understanding token structure and diagnosing validation failures, but it should only be used for inspection, not as part of any production verification flow.

Important production considerations

Using JWTs safely in production requires more than correct syntax or library defaults. Many JWT-related incidents stem from operational shortcuts rather than cryptographic failures, so token handling needs to be treated as an ongoing lifecycle concern.

In practice, this typically includes the following:

- Rotate signing keys regularly and publish them via a JWKS endpoint, so APIs can verify tokens without hard-coded keys or coordinated redeployments.

- Keep access tokens short-lived and limit the data stored in claims to reduce the blast radius if a token is leaked or intercepted.

- Treat refresh tokens as sensitive credentials, and protect them with rotation, revocation, and server-side tracking to prevent replay attacks.

- Log and monitor token validation failures, since repeated failures often indicate misconfiguration, misuse, or attempted abuse.

JWTs are powerful building blocks, but their safety depends entirely on how deliberately they are issued, verified, rotated, and monitored over time.

Expanding to other languages

Although the examples in this guide use Node.js, the underlying JWT concepts apply consistently across languages and platforms. Most ecosystems provide mature libraries for creating and validating tokens, but the same security principles still apply regardless of implementation.

Common options include:

- Python: Libraries such as PyJWT are widely used for signing and verifying JWTs.

- Java: Libraries like jjwt integrate well with popular Java frameworks and identity systems.

- Go: The golang-jwt package provides a lightweight and explicit approach to token handling.

Each language has its own conventions and tooling, but the fundamentals remain unchanged: JWTs must be issued intentionally, validated rigorously, and used as part of a broader authentication and authorization architecture, not as a standalone security solution.

Why use JWTs? The key benefits

JWTs bring a host of benefits that make them a widely used choice for managing authorization state in distributed systems:

- Stateless simplicity: JWTs encapsulate all necessary identity claims within the token itself, so servers do not need to maintain session state or track every client. This greatly simplifies architecture and reduces operational load on authentication services.

- Boosted performance: Because JWTs are compact and self-contained, they can be transmitted efficiently over the network and validated locally by APIs without additional round-trips to a central session store, improving latency and throughput.

- Cross-platform flexibility: JWTs are standardized and supported across ecosystems such as Java, Python, Node.js, and Go, enabling developers to maintain consistent token handling across services and platforms.

- Built-in integrity guarantees: Every JWT is digitally signed. When properly verified, this signature establishes that the token has not been tampered with and comes from a trusted issuer. For additional confidentiality, JWTs can also be encrypted using JSON Web Encryption (JWE), making the payload unreadable to third parties even if intercepted.

Case studies: What modern JWT vulnerabilities teach us

Even though JWTs themselves define a secure format for carrying claims, implementation mistakes or library vulnerabilities can still introduce serious risks. Examining real incidents shows why rigorous validation and secure defaults are essential:

- Issuer validation flaw in fast-jwt (2025): A JWT library called fast-jwt did not properly validate the iss (issuer) claim when it allowed an array of strings instead of a strict single value. A crafted token with a mixed array, including an attacker-controlled domain, could be accepted as valid, enabling forged tokens to bypass intended protections. This was addressed in later releases of the library.

- Algorithm bypass issue in python-jose (2025): A vulnerability in the python-jose JWT library permitted tokens with alg: none to be accepted without requiring a valid signature. An attacker could forge tokens with arbitrary claims and bypass authentication checks if the application did not explicitly reject “none” algorithms.

- Library error checking gaps in golang-jwt (2024): An implementation issue in versions of golang-jwt led to unclear error behavior in the ParseWithClaims function. Improper error handling could cause token validation to appear successful when it should have failed, underscoring the need for careful error handling and robust test coverage.

These cases illustrate that the JWT format is secure, but the security of a system depends on how libraries implement verification, enforce claim checks, and reject unsafe tokens. All of these flaws have since been addressed in patch releases, but they serve as strong reminders that developers must keep libraries up to date and defend against protocol misuse.

Best practices for using JWTs

JWTs are simple by design, but using them safely in production requires discipline around storage, validation, and lifecycle management. Most JWT-related issues arise not from the format itself, but from how tokens are issued, stored, and reused over time.

The following practices help reduce risk while preserving the benefits of JWT-based systems:

- Use secure, context-appropriate storage mechanisms.

In browser-based applications, JWTs are often stored in HTTP-only, secure cookies to prevent access from client-side JavaScript and reduce exposure to XSS attacks. These cookies should always be sent over HTTPS and configured with appropriate SameSite attributes. For non-browser clients such as mobile apps or service-to-service calls, tokens are typically transmitted in authorization headers, with transport security handled at the protocol level.

- Always set explicit expiration times on access tokens.

Every JWT should include an exp claim, and access tokens should be short-lived. Limiting token lifetime reduces the window of misuse if a token is leaked. When longer sessions are required, short-lived access tokens should be combined with refresh tokens rather than extending the validity of the access token.

- Design token lifecycle handling around expiration, not revocation.

JWTs are not well-suited to real-time revocation without introducing additional state. Instead of relying on token blacklists, production systems typically allow tokens to expire naturally and issue new ones through controlled refresh flows. Once expired, tokens should be rejected unconditionally and removed from client storage to prevent reuse.

- Never place sensitive data in the token payload.

JWT payloads are Base64URL-encoded, not encrypted. Anyone in possession of the token can decode its contents. Personally identifiable information, secrets, or internal system data should never be included unless the token is explicitly encrypted using JWE and the threat model justifies it.

- Keep tokens small and purpose-driven.

JWTs should carry only the claims required for validation and authorization decisions. Overloading tokens with excessive data increases payload size, impacts network performance, and makes future changes harder. Lightweight tokens are easier to rotate, validate, and reason about across services.

Following these practices keeps JWT usage predictable and auditable, and ensures that tokens remain a reliable mechanism for carrying claims rather than a hidden source of security risk.

Scenarios and use cases for JWTs

JWTs are best understood as a mechanism for carrying verified claims across system boundaries. They are most effective when used as part of a broader authentication and authorization architecture rather than as a standalone solution.

Common scenarios where JWTs are a strong fit include:

OpenID Connect (OIDC) and Identity Tokens

JWTs serve as the standard format for ID tokens in OpenID Connect (OIDC). In this context, an ID token is issued after successful authentication and is used by client applications to verify the user’s identity and retrieve basic profile information.

Because ID tokens are self-contained and cryptographically signed, client applications can validate them locally without having to repeatedly call the identity provider. This makes JWTs particularly effective in enterprise environments where identity needs to be propagated reliably across multiple applications and platforms.

Distributed Session Context in Modern Applications

JWTs are often associated with stateless architectures, but they can also be used in hybrid session models where limited session state still exists. In these setups, JWTs carry session context, such as user identity or authorization scope, while the system retains control over session lifecycle through expiration and refresh mechanisms.

In microservice-based systems, JWTs allow each service to independently validate incoming requests without relying on a centralized session store. This enables consistent request verification as a request moves across services, improving scalability while maintaining clear trust boundaries between components.

Securing API Endpoints

JWTs are commonly used as access tokens to secure API endpoints. Each request includes a token that represents an authorization decision already made by an upstream system, such as an OAuth authorization server.

APIs validate the token’s signature and claims, such as audience, issuer, and scope, to determine whether the requested operation is allowed. This approach avoids repeated authentication checks and enables APIs to make fast, local authorization decisions while remaining decoupled from identity systems.

Single Sign-On (SSO) Across Multiple Services

JWTs are a natural fit for Single Sign-On (SSO) implementations, where users authenticate once and gain access to multiple services within the same ecosystem. In these environments, tokens issued by a trusted identity provider can be reused across applications, reducing friction for users while maintaining consistent enforcement of access policies.

JWT-based SSO is particularly common in enterprise platforms, internal tooling, and cloud-based service suites, where users routinely interact with many applications that share a common identity layer.

Across all of these scenarios, the key principle remains the same: JWTs carry claims, not trust. Trust is established by how tokens are issued, validated, and managed, not by the token's format.

Security risks and when not to use JWTs

JWTs are a powerful mechanism for carrying claims, but they introduce specific risks that teams need to understand before adopting them. Most of these risks are not inherent flaws in JWT itself, but consequences of how tokens behave once issued.

Key risks to account for include:

- Token theft has an immediate impact.

If an attacker gains access to a valid JWT, they can impersonate the token holder until the token expires. Mitigation relies on short-lived access tokens, secure transport (HTTPS), careful client-side storage, and strong validation on every request.

- Immediate revocation is difficult by design.

Stateless JWTs cannot be revoked instantly without introducing additional state, such as revocation lists or token introspection. Applications that require hard, immediate session termination, such as financial systems or high-risk admin tooling, may find traditional server-side sessions easier to control.

- Misconfiguration can silently weaken security.

Accepting unexpected signing algorithms, skipping issuer or audience checks, or trusting unvalidated claims can all lead to authorization bypass. These failures often go unnoticed until exploited.

- Overuse can complicate authorization logic.

JWTs work best when they carry minimal, well-defined claims. Using them to encode complex or frequently changing authorization states can make systems harder to reason about and harder to evolve safely.

JWTs are not always the right choice. Applications that require fine-grained session control, frequent permission changes, or guaranteed real-time revocation may be better served by traditional server-side sessions or token introspection–based approaches.

Conclusion

JWTs are not an authentication system, but a standardized token format for carrying verified claims across services. When used within frameworks like OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect, they enable scalable, decoupled request validation, provided tokens are issued carefully, validated rigorously, and managed throughout their lifecycle.

If you’re designing or reviewing an authentication system, start by clarifying where JWTs fit in your architecture, enforcing strict validation and expiration policies, and evaluating whether stateless tokens match your security and revocation requirements. For a broader comparison of approaches, explore our guide to API authentication in B2B SaaS to decide when JWTs are the right choice, and when they aren’t.

FAQ

1. How does Scalekit help with JWT management in production systems?

Scalekit helps teams issue, sign, rotate, and validate JWTs as part of a broader identity and authorization setup. Instead of building token infrastructure from scratch, teams can rely on Scalekit to handle key rotation, standards-compliant token issuance, and secure verification flows that integrate cleanly with OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect.

2. Can Scalekit work with existing JWTs and identity providers?

Yes. Scalekit is designed to integrate with existing identity providers and applications rather than replace them. It can validate JWTs issued by trusted authorities, publish JWKS endpoints, and enforce consistent token policies across services, which makes it easier to scale and standardize authentication flows.

3. Are JWTs better than traditional server-side sessions?

JWTs are not inherently better; they solve a different problem. JWTs work well in distributed systems where services need to validate requests independently, while server-side sessions are often better when immediate revocation and centralized control are required. The right choice depends on your architecture, security requirements, and operational constraints.

4. Should JWTs be stored in cookies or authorization headers?

It depends on the client and threat model. Browser-based applications often use HTTP-only, secure cookies to reduce exposure to XSS, while mobile apps and service-to-service communication typically send JWTs in authorization headers. Neither option is universally safer without proper validation and transport security.

5. When should you avoid using JWTs altogether?

JWTs may not be a good fit if your application requires real-time session revocation, frequent permission changes, or heavy server-side session logic. In these cases, stateful sessions or token introspection–based approaches can offer clearer control and simpler security guarantees.

.webp)