Enterprise MCP: How Identity, SSO, and Scoped Auth Actually Work

TL;DR

- MCP is moving from local experiments to real enterprise workflows such as incident response, analytics access, and internal tooling, where identity, control, and auditability are non-negotiable.

- Enterprises evaluate MCP not as a protocol, but as a new access surface that must integrate cleanly with SSO, RBAC, and existing security and compliance models.

- Making MCP enterprise-ready requires five foundations: clear identity boundaries, method-level governance, end-to-end observability, consistent policy enforcement, and tight integration with enterprise IdPs.

- Authentication and authorization are central to this model: SSO establishes user identity, while scoped MCP auth determines which actions IDEs and agents are allowed to perform.

- For workflows that span multiple systems, MCP must be complemented by Cross-App Access (XAA) to ensure identity and policy remain consistent beyond the first hop.

When MCP enters enterprise reality

A developer installs an MCP-powered agent in their IDE to speed up everyday work, such as pulling logs during an incident, querying metrics, or running quick diagnostics without switching tools. In early tests, everything works exactly as expected. The agent responds instantly, the workflow feels smooth, and MCP is a clean way to connect AI-assisted tooling to internal systems.

That confidence changes when the same workflow is connected to real production systems. During an incident drill, the agent pulls sensitive logs, checks a cost dashboard, and inspects a live service. Nothing technically breaks, but when platform and security teams review the activity, uncomfortable questions surface. It isn’t immediately clear whether the actions originated from the developer, the IDE, or the agent itself; whether the appropriate permissions were applied; or whether the activity can be reliably audited after the fact.

This is the point at which MCP stops being a local developer experiment and is treated as an enterprise system. As MCP spreads across internal tools, incident response, analytics, and even external workflows like partner support or customer-facing automation, enterprises shift their focus from “does this work?” to “can this be governed safely?” The rest of this article uses this scenario as a running thread to unpack what large engineering teams need to make MCP production-ready across control, observability, security, and eventually authentication and SSO.

Why enterprises evaluate MCP differently

Enterprise adoption changes how MCP is evaluated because MCP becomes a real integration point into production systems. When the IDE-based agent from the opening scenario runs locally, it behaves as a developer convenience that accelerates debugging or exploration. Once that same workflow is connected to production logs, analytics platforms, or internal tooling, MCP is no longer isolated. It becomes another path through which data is accessed, and actions are triggered, and that shift alone is enough for enterprises to treat MCP differently from developer-only tooling.

Enterprise workflows expose MCP to operational and organizational constraints that prototypes never encounter. Large engineering teams already use MCP for incident triage, internal analytics, cost investigations, and developer support workflows. In these environments, MCP-driven actions interact with shared systems and sensitive data. A log read during an incident drill affects production observability. An analytics query triggered by an agent runs against governed datasets. A diagnostic action can influence on-call decisions. These workflows technically work, but they now reside within environments with established rules for access, change control, and accountability.

Common enterprise MCP use cases that trigger this shift include:

- Incident triage and production log access

- Internal analytics and reporting

- Cost and usage investigation

- Developer support and on-call tooling

Enterprise evaluation focuses on governance questions rather than protocol mechanics. When platform and security teams review MCP activity from the running scenario, they seek clarity on who initiated each action, whether the action matched approved permissions, and whether the activity can be reconstructed later from logs and audits. If MCP-driven actions bypass existing controls or obscure attribution, the workflow is blocked even if the MCP implementation itself is correct.

Enterprise failure modes repeat because the exact expectations apply to every integration. Across organizations, MCP pilots stall when permissions are overly broad, actions cannot be traced back to an individual, agents accumulate more access than intended, or downstream systems reject requests due to missing or mismatched context. These issues do not reflect problems with the MCP protocol. They reflect what happens when MCP is introduced without the same governance, observability, and policy foundations that enterprises already require from APIs and internal services.

The five foundations enterprises expect before approving the MCP

Enterprise MCP deployments succeed or stall due to a small set of recurring issues. When MCP starts interacting with production logs, analytics backends, configuration services, or ticketing systems, platform, IAM, and security teams evaluate it using the same criteria they apply to other internal integrations. These are not abstract design ideals. They are practical checks used during architecture reviews, security sign-offs, and production readiness assessments. Across organizations adopting MCP, five foundations consistently determine whether a deployment moves forward.

1. Identity boundaries across humans, clients, and agents

Identity boundaries determine whether enterprise systems can reliably attribute actions. In the running incident scenario, MCP-driven log access becomes problematic when it is unclear whether the action came from a human developer, an IDE extension, or an autonomous agent. Enterprises require MCP to represent these actors distinctly so downstream systems can authorize requests correctly and explain behavior after the fact. Without clear boundaries, audit trails break down, and incident reviews turn into guesswork.

2. Governance that aligns MCP methods with enterprise permissions

Governance defines how MCP methods fit into existing organizational controls. Enterprises expect methods like logs.read, analytics.query, or incidents.trigger to map cleanly to established roles, approval processes, and change policies. This goes beyond scopes alone. Teams look for alignment with existing RBAC models, permission reviews, and revocation workflows. When MCP introduces a parallel permission system or bypasses approval paths, prototypes work, but production deployments stall during review.

3. Observability and auditability across MCP-driven workflows

Observability determines whether MCP activity can be trusted during incidents and reviews. Enterprise teams need to reconstruct what happened across complex workflows, especially when agents are involved. That requires logs, traces, and metadata that clearly connect:

- The initiating user

- The client or agent involved

- The MCP method invoked

- The downstream systems affected

In incident response or analytics workflows, missing attribution or broken traces become immediate blockers. Enterprises expect MCP to integrate cleanly with existing logging pipelines, SIEM systems, and audit tooling so that MCP activity can be investigated alongside other production events.

4. Security and policy enforcement at MCP boundaries

Security controls ensure MCP does not become an unintended escalation path. Enterprises expect MCP servers to enforce the same guardrails applied to other internal services, including client allowlists, rate limiting, input validation, and strict permission checks. These controls matter most when agents automate actions across systems. Without consistent enforcement at the MCP boundary, small automation shortcuts can quietly turn into high-risk access paths.

5. Integration with enterprise SSO and identity providers

Identity integration connects MCP to the systems enterprises already trust. Authentication, MFA, conditional access, session limits, and lifecycle policies are expected to originate from the organization’s IdP rather than being reimplemented inside MCP. SSO anchors MCP actions to real enterprise identities, while IdP-managed policies ensure access decisions remain consistent across tools. This foundation enables MCP to participate in enterprise environments without weakening existing identity controls.

How SSO and OAuth support controlled access in enterprise MCP deployments

Enterprise MCP deployments require explicit identity because MCP requests interact with production systems. When the IDE-based workflow from the opening scenario reaches real logs, analytics platforms, or configuration services, every request must be attributable and policy-evaluated. At that stage, authentication and authorization stop being implementation details and become supporting infrastructure that enables governance, auditability, and least-privilege access across enterprise systems.

SSO provides the source of truth for who is acting in an MCP workflow. When a developer invokes an MCP-powered tool from an IDE or triggers an agent-assisted action, their identity must originate from the enterprise identity provider, such as Okta, Entra ID, or Google Workspace. This ensures that the action is tied to an identity that already participates in enterprise lifecycle management, conditional access, and audit controls. If MCP relies on local credentials or agent-specific identities instead, downstream systems lose consistency in authorization decisions.

OAuth links the verified identity to authorized MCP actions. Rather than issuing broad or long-lived tokens, enterprises bind OAuth scopes directly to MCP methods like logs.read, analytics.query, or incidents.trigger. This keeps MCP access aligned with existing RBAC models and approval processes. The result is that IDEs and agents operate under the same least-privilege constraints as internal APIs, rather than introducing a parallel access model.

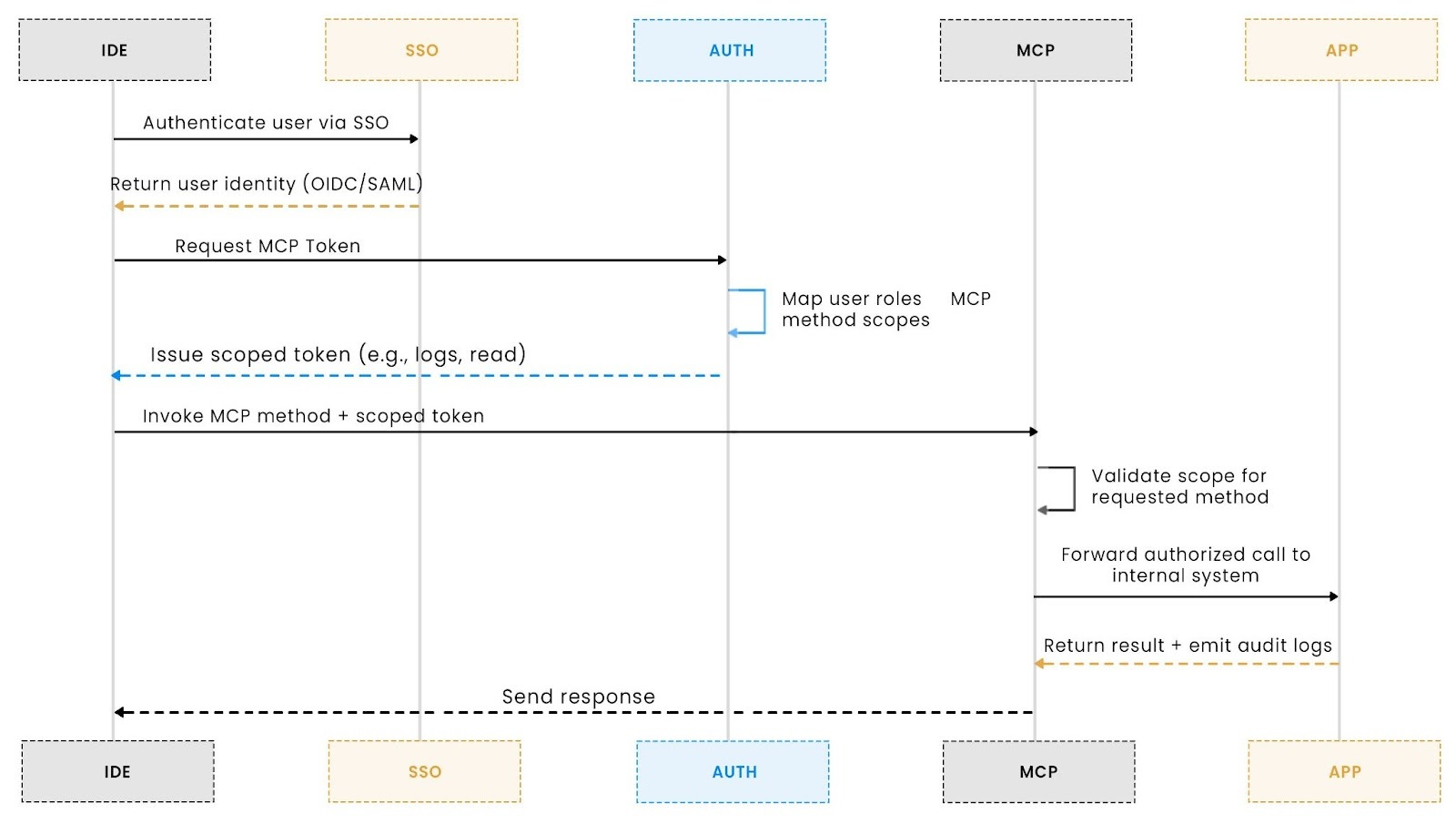

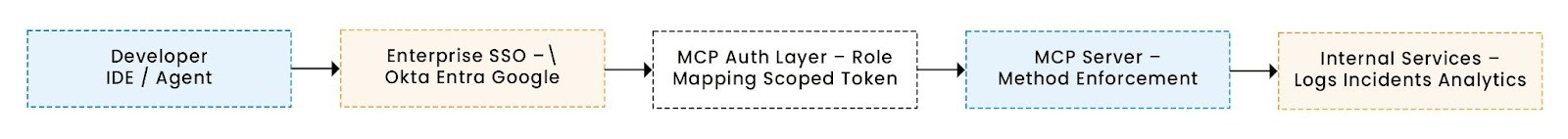

The diagram below shows how these responsibilities are separated but connected in a typical enterprise deployment:

In this flow:

- The IDE authenticates the user through enterprise SSO and receives a verified identity.

- The IDE requests an MCP token from an auth layer that understands MCP-specific scopes.

- The auth layer maps enterprise roles to allowed MCP method scopes and issues a scoped token.

- The MCP server validates the method scope before forwarding the call.

- Internal systems receive authorized requests and emit audit logs tied to the originating identity.

This separation of responsibilities is intentional. SSO establishes who the user is. The MCP auth layer determines what actions are allowed. The MCP server enforces those permissions at the method boundary. Together, they form a single identity and authorization flow that fits cleanly into existing enterprise security models.

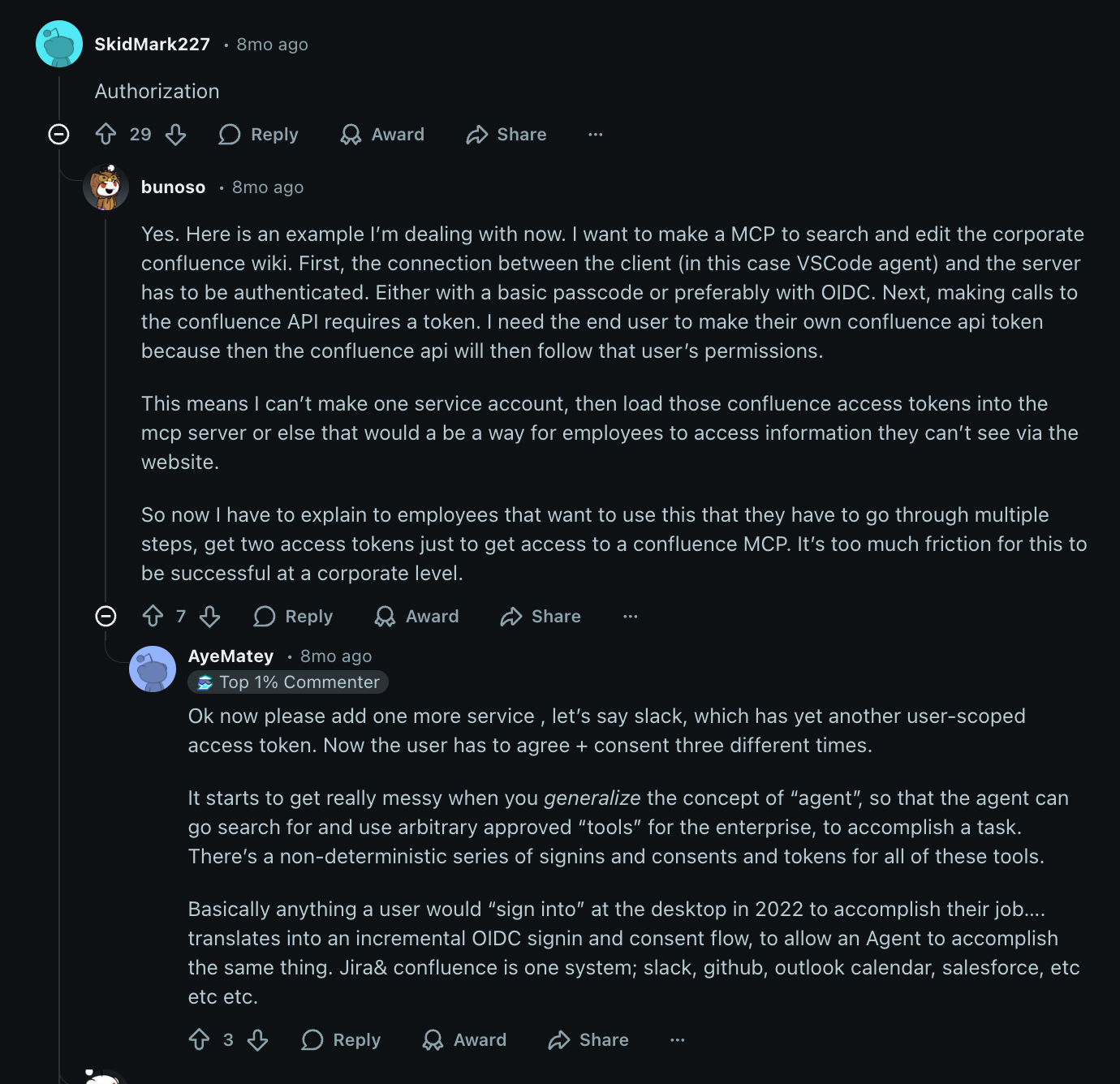

Where authentication friction shows up as MCP workflows scale

Authentication friction becomes visible when MCP workflows expand beyond a single system. In early experiments, an MCP-powered agent might interact with one internal service using a single token. As teams extend the same workflow to logs, analytics, cost tools, and incident systems, each additional integration introduces new credentials, consent flows, or token handling logic. What felt smooth at first quickly becomes brittle and difficult to operate.

This friction often marks the point where MCP prototypes stall in large organizations. The protocol still works, but identity handling fragments as workflows grow. Tokens are issued with unclear lifetimes, permissions become overly broad to avoid repeated prompts, and agents start carrying credentials that are hard to rotate or audit. These shortcuts make demos succeed but raise immediate concerns during security and platform reviews.

Authentication friction rarely appears in isolation. As MCP workflows touch more systems, teams also encounter:

- Approval delays when access paths are unclear

- Security reviews triggered by opaque identity flows

- Missing or incomplete audit trails during incident analysis

Together, these issues signal that MCP has crossed from experimentation into enterprise territory. At that stage, friction is not a usability problem to be smoothed over. It is a sign that MCP needs more precise boundaries, stronger governance, and better integration with existing enterprise controls before it can scale safely.

Why enterprises introduce an MCP-aware authentication layer

Enterprises introduce an MCP-aware authentication layer to avoid fragmented identity handling as workflows scale. When each IDE extension, agent, or internal tool manages credentials independently, the identity context quickly breaks down. Tokens become inconsistent, permissions drift, and downstream systems receive requests they cannot reliably trust or audit.

An MCP-aware auth layer centralizes these responsibilities without changing how enterprise identity already works:

- SSO establishes and verifies the user identity

- OAuth scopes map enterprise permissions to MCP methods

- The auth layer resolves roles and enforces policy consistently

- MCP servers receive scoped requests that they can validate at the method boundary

This structure preserves end-to-end attribution and prevents failures in the opening scenario, where production actions could not be clearly tied back to a verified user or approved permissions. Rather than adding new identity models, the auth layer aligns MCP with existing enterprise controls and review expectations.

Example architecture for enterprise MCP in large organizations

Once MCP moves beyond a prototype, enterprises quickly realize it must pass through the same identity, authorization, and audit layers that protect every other internal tool. Whether the workflow involves incident triage, log retrieval, or analytics automation, the MCP request cannot be routed directly to internal services; it must pass through a structured identity pipeline.

A typical enterprise architecture ends up looking like this:

How the identity pipeline works

- SSO verifies who the user is.

- The MCP Auth Layer determines what that identity is allowed to do by issuing a token that contains only the method scopes the organization permits.

- MCP Server enforces those scopes at the method level.

- Internal services validate logs, incidents, queries, and side effects using metadata that links the callback to the originating user and client.

This layered flow prevents the failure from our opening scenario, where an agent accessed production logs without a clear user identity or attempted actions beyond the developer’s permissions.

A practical example: role-to-scope mapping

Enterprises don’t want new permission models. They expect MCP to align with the RBAC structures they already use. In practice, this usually looks like a simple role-to-scope mapping enforced by the MCP Auth layer:

roles:

developer:

- logs.read

- analytics.query

sre:

- logs.read

- logs.debug.write

- incidents.trigger

When the developer signs in via SSO, the MCP Auth Layer resolves their role and issues a token with only the scopes they are authorized for. If an autonomous agent acts on their behalf, it inherits the exact boundaries, no hidden privilege escalation, and no ambiguous access.

This is the “missing middle” that early MCP prototypes skip, and the layer enterprises insist on before approving MCP for production use.

Where Scalekit fits into this architecture

Everything described above, SSO integration, role resolution, and scoped token issuance, is precisely what Scalekit’s Enterprise MCP Auth provides out of the box.

Scalekit removes the need for teams to manually wire together SAML/OIDC, token rules, role mappings, and identity lifecycles. Using its Secure MCP with Enterprise SSO workflow, teams can:

- Connect enterprise IdPs (Okta, Entra ID, ADFS) via SAML or OIDC

- Enforce domain-level SSO for all developers (e.g., @company.com)

- Apply role-based MCP method scopes

- Emit audit-ready metadata for every MCP request

Instead of stitching together identity flows manually, Scalekit acts as the auth control plane between the IdP and the MCP server, ensuring every IDE or agent action is attributable, scoped, and reviewable.

With this architecture in place, MCP stops being a risky integration point and becomes a first-class, enterprise-approved access surface.

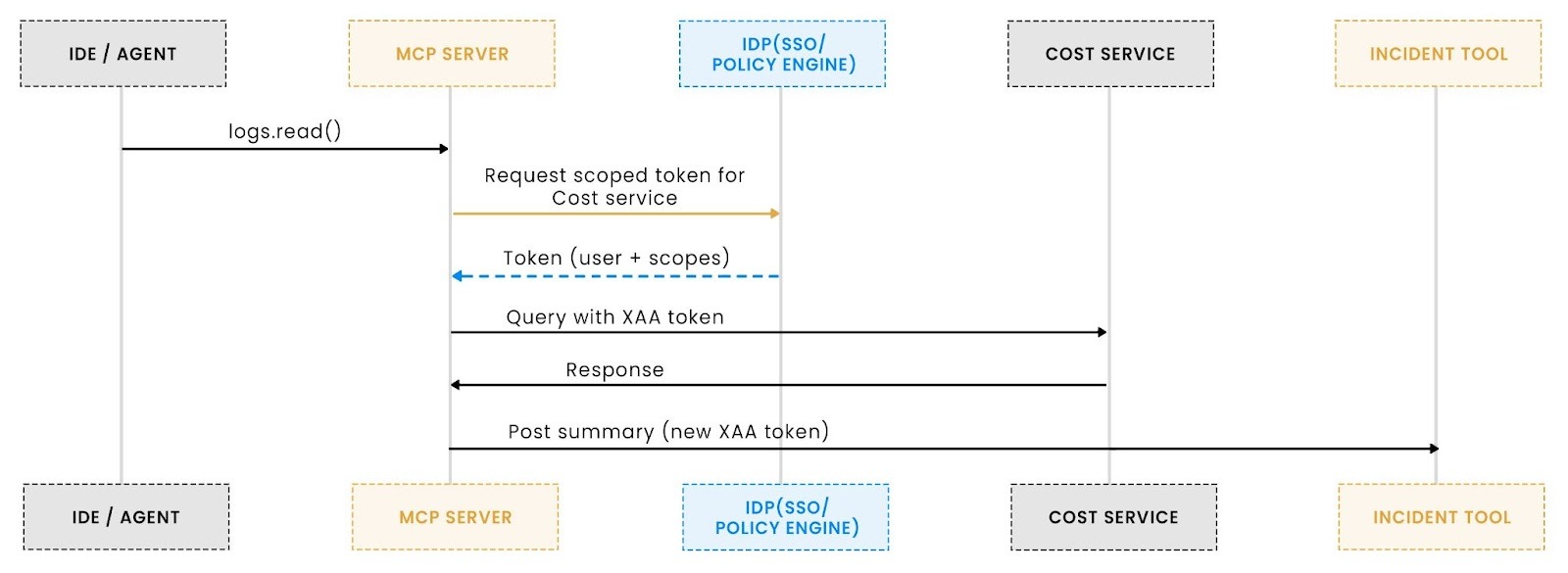

How Enterprise MCP relates to Cross-App Access (XAA)

Once MCP starts powering real workflows, it rarely stays confined to a single server. The same workflow that begins in an IDE often fans out across multiple internal systems.

Consider the debugging flow we’ve been using throughout this article:

A user pulls logs → the agent enriches them → then queries a cost tool → then posts a summary to an incident dashboard.

This is a multi-hop workflow spanning several internal applications. MCP governs the first interaction, but it does not define how identity and authorization should propagate beyond that initial boundary.

What MCP secures and Where It Stops

MCP is responsible for securing the entry point into a workflow:

- User identity comes from SSO

- Method-level scopes (e.g., logs.read, analytics.query) are enforced

- The MCP server knows exactly who invoked what

This works well for IDE or agent-to-MCP server interaction.

But once an MCP method triggers downstream behavior, querying another internal service, updating a dashboard, or calling an automation, MCP’s guarantees no longer apply. At that point, the next service needs its own trusted way to evaluate identity and policy.

This is where early enterprise MCP pilots often fail: the first hop is secure, but subsequent calls lack consistent identity context or enforceable policy.

Where XAA fits: securing every hop after MCP

Cross-App Access (XAA) addresses this gap by making the IdP the control plane for every hop, whether the call is app-to-app or agent-to-app.

With XAA in place:

- Each downstream service receives an IdP-issued token

- User identity, role, and conditional access policy are already embedded

- Services do not rely on forwarded or handcrafted credentials

- Authorization decisions remain centralized and auditable

In other words, MCP governs how a workflow starts, while XAA governs how that workflow safely continues across applications.

MCP secures the entry point into the workflow. XAA ensures the same identity and policy context persists as the workflow spans additional systems.

Why enterprises use MCP + XAA together

Using only MCP gives you:

- Method-level governance

- Clear user and agent attribution

- Scoped token enforcement

Using XAA on top gives you:

- Policy continuity across multiple services

- Least-privilege enforcement on every hop

- A complete audit trail from IDE to agent to every downstream system

This is why enterprise architecture teams increasingly evaluate MCP and XAA together rather than as separate ideas. MCP handles the endpoint; XAA handles the ecosystem.

Together, they form a complete agentic authorization model for agentic and multi-application workflows without weakening identity controls as automation scales.

Enterprise evaluation checklist for MCP deployments

Enterprise approval for MCP shifts once workflows move into production. At that stage, MCP is no longer evaluated by individual developers but by platform engineering, IAM, and security teams who treat it like any other internal integration surface. The core question changes from whether MCP works to whether it can be operated, governed, and audited safely at scale.

1. Identity mapping across MCP interactions

Identity mapping determines whether MCP actions can be reliably attributed. Reviewers verify that MCP can consistently identify who initiated each action and in what context. They typically check that:

- User identity originates from enterprise SSO

- Client and agent identities are distinct from the human user

- Every MCP action can be traced back to a verified individual

This directly addresses the opening scenario, where a failed review of sensitive log access could not be attributed with confidence.

2. Method-level authorization enforcement

Method-level authorization ensures MCP actions align with enterprise permissions. Reviewers expect:

- Each MCP method (logs.read, analytics.query, deploy.execute) to map to explicit scopes

- No default or overly broad permissions for IDEs or agents

- Alignment between MCP scopes and existing RBAC or group-based models

When method-level authorization is missing or loosely enforced, MCP deployments are commonly blocked during security review.

3. Scope design and long-term governance

Scope governance determines whether MCP remains manageable over time. Enterprises verify that:

- Scopes are granular, reviewable, and revocable

- Scope changes do not silently expand access

- MCP does not introduce a parallel permission model

Early MCP prototypes often pass initial tests but fail here as usage grows and permissions become difficult to reason about safely.

4. End-to-end logging and traceability

Auditability determines whether MCP activity can be reconstructed after the fact. Reviewers expect a continuous trace across:

- SSO establishes the user identity

- The auth layer resolving roles and scopes

- MCP server method invocation and outcome

- Downstream systems recording side effects

If any layer drops metadata, MCP frequently fails approval because incidents and access reviews cannot be reliably reconstructed.

5. Policy integration with SSO and identity providers

Policy integration ensures MCP does not become its own authority. Enterprises confirm that:

- MFA, device trust, session limits, and conditional access come from the IdP

- MCP inherits these policies rather than bypassing them

- Authorization decisions remain centralized

This keeps MCP aligned with the same security posture as other internal tools.

6. Cross-application access requirements

Cross-app access determines whether MCP workflows remain contained within a single app or expand across systems. Teams assess:

- Whether MCP secures only the IDE or the agent to the MCP server interaction

- Whether downstream services require IdP-issued tokens via XAA

- Whether identity and policy context remain intact across hops

This is critical for incident tooling, analytics pipelines, cost dashboards, and chained agent workflows.

7. Operational governance and rollout controls

Operational governance ensures MCP can be introduced safely. Reviewers often look for:

- Clear change management and approval processes for new MCP methods

- Controlled rollout strategies for agents and integrations

- Defined ownership for MCP servers and auth configuration

These checks prevent MCP from bypassing existing operational safeguards.

8. Deployment readiness indicators

Deployment readiness indicates whether MCP can proceed. Enterprises typically expect:

- Explicit identity boundaries between users, clients, and agents

- Method scopes aligned with RBAC

- Complete audit chains

- Mandatory SSO and IdP enforcement

- XAA patterns where workflows span systems

When these indicators are present, MCP deployments consistently pass review rather than stalling at the security gate.

Conclusion

The core lesson from the debugging scenario we began with is simple: MCP doesn’t fail in enterprises because the protocol is immature; it fails when identity, authorization, and auditability are treated as afterthoughts. Once MCP workflows reach production logs, analytics systems, or cost tooling, teams must know exactly who triggered each action, whether an agent acted within policy, and how permissions propagated across systems. Without those guarantees, even a well-designed MCP prototype becomes untrustworthy in a real enterprise environment.

What makes MCP enterprise-ready is not a single feature, but a set of expectations enterprises already apply to every internal system: SSO-anchored identity, method-level authorization aligned with RBAC, consistent observability, and policy enforcement that prevents silent privilege escalation. When workflows span multiple systems, Cross-App Access (XAA) extends those guarantees beyond the MCP server, ensuring identity and policy remain intact across every hop.

The takeaway is straightforward: MCP scales only within large organizations when it integrates cleanly with the enterprise identity fabric. Teams evaluating MCP should think beyond “getting a token” and design for control, attribution, and auditability from day one. For deeper guidance, Aaron Parecki’s Enterprise-Ready MCP, Scalekit’s Cross-App Access model, and the CIMD client metadata approach offer concrete patterns that closely align with how enterprises deploy MCP in practice.

FAQ

1. What problem does MCP actually solve for enterprise teams?

MCP provides a structured, identity-aware way for IDEs and agents to interact with internal systems using well-defined methods and scopes. Without MCP, organizations rely on ad-hoc scripts or custom APIs that lack consistent identity mapping, auditability, or policy enforcement. MCP gives enterprises a governed, traceable surface for agentic, IDE-driven automation.

2. Why can’t enterprises rely on traditional OAuth authentication for MCP workflows?

OAuth alone does not define method-level permissions, client identity surfaces, or agent attribution. Enterprises need to know which user performed an action, which agent executed it, and which scopes applied at every step. MCP defines these boundaries, while OAuth is only one component of the identity pipeline.

3. How does MCP reduce security risk in incident and debugging workflows?

MCP forces teams to define explicit scopes (e.g., logs.read, analytics.query) that map to RBAC roles. This prevents agents or IDE plugins from overreaching into sensitive systems. MCP’s structured identity boundary ensures logs, production data, and internal tools are accessed only by verified users with enforceable permissions.

4. How does Scalekit help enterprises implement MCP with SSO and scoped authorization?

Scalekit provides an MCP Auth layer that integrates directly with identity providers such as Okta or Entra ID. It handles SSO login, token issuance, and method-level scope enforcement. Instead of building custom auth flows, teams can adopt a standardized pattern in which identity is verified via SSO, and scoped tokens govern which MCP methods a user or agent may call.

5. When does an enterprise need Cross-App Access (XAA) in addition to MCP?

MCP governs the first-hop IDE or agent-to-MCP server connection. But many workflows trigger downstream calls to analytics systems, cost dashboards, configuration services, or incident tools. XAA becomes necessary when those second and third hops require verified identity and enforceable policies. XAA ensures that downstream services receive tokens issued by the IdP, rather than having them forwarded by MCP, preserving least-privilege access across the entire workflow chain.