OTP vs magic links: Choosing the right passwordless authentication method

How many apps do you use at work? A 2024 estimate pegged it at 94 on average. With this whopping number comes the burden of setting,remembering, and resetting passwords. So it’s no surprise that passwordless authentication methods are booming.

Two of the most common passwordless methods are One-Time Passwords (OTP) and magic links. Both eliminate the need for a user-created password, but they work in different ways: with OTP, the user is sent a code (via SMS, email, or app) which they must manually enter, whereas a magic link lets the user authenticate with a single click on a unique URL.

In this blog, we’ll compare OTPs and magic links across five critical dimensions from user experience and security to implementation.

1. User experience comparison

When it comes to user experience, both OTPs and magic links aim to simplify login, but they offer slightly different flows.

Flow

An OTP login typically requires the user to switch context, retrieve a code, and type it in, which is an extra step compared to a magic link.

In contrast, clicking a magic link directly continues the login process with fewer steps. In practice, both methods interrupt the user’s flow since the user must leave the original app or page to check their messages or email.

This context-switch can be momentarily jarring. On mobile, a typical magic link login might involve opening the app, switching to the email app for the magic link, and click the link.

OTP-based logins have a similar interruption (open SMS or email to get the code), but many users are accustomed to this from banking or other services.

Familiarity

This brings us to the familiarity aspect: OTPs are very familiar to most users; people encounter 4-6-digit codes for everything from banking to account recovery, so the process is intuitive.

Magic links, while simple, are a newer concept. Not everyone immediately understands that clicking an emailed link logs them in. This lack of familiarity can cause confusion for some users and even increase drop-off rates if they don’t trust or grasp the process. Educating users (e.g. with a clear prompt like “Check your email for a login link”) can mitigate this.

Friction and convenience

Magic links remove the step of typing, which can reduce user friction: no risk of mistyping a code or password, just a tap to log in. This low-effort flow is great for smooth login. OTPs introduce a bit more friction since the user must transcribe the code.

However, modern mobile OSes often auto-detect and suggest OTP codes from SMS, which significantly eases the process for users. In other words, typing a 6-digit code when prompted has become fairly quick, especially on mobile devices that offer one-tap auto-fill for SMS OTPs. Both methods avoid the major hassles of passwords (nothing for the user to remember or reset).

Cross-device use

A subtle UX difference is how the login can be completed across devices. With a basic magic link implementation, a user could initiate login on one device and click the link on another, potentially causing confusion or an inconsistent session. (In fact, some security-conscious implementations deliberately invalidate magic links if opened on a different device or browser than where it was requested, forcing the user back to the original device or to use an OTP instead.)

OTPs are inherently transferable. A user can request a code on one device and enter it on another. But typically the expectation is the user enters it on the same device where they initiated login. Both methods ideally keep the user in one context for a smoother experience.

2. Security considerations

Security is often the deciding factor in authentication choices. Both OTPs and magic links remove the risks of static passwords (like password reuse and database breaches) since authentication is tied to a one-time secret. However, each method has its own security profile and potential vulnerabilities:

One-Time Password (OTP) security

OTPs are commonly used in high-security contexts (banks, fintech, etc.) because a short-lived code that expires and cannot be reused offers strong protection against credential theft. OTPs can also serve as a second factor (MFA) on top of passwords, adding another layer of defense. The primary risks with OTPs depend on the delivery channel:

SMS OTP: SMS-based OTPs are vulnerable to telecom attacks such as SIM swapping or interception. An attacker who hijacks someone’s phone number could receive their codes and gain access. Using a reputable OTP provider with fraud protections is crucial. Also, SMS OTP messages can be delayed or fail to arrive, which not only hurts UX but can be a security issue if users try risky workarounds.

Email OTP: If OTP codes are sent via email, then the security becomes similar to magic links (reliant on the email account’s security). An emailed code could potentially be phished or intercepted in transit, though if using TLS email transport and one-time codes, interception is quite difficult. There is also the possibility of social engineering – attackers tricking users into revealing their code – which is a general risk for any OTP method.

Authenticator app OTP: OTP codes from authenticator apps (TOTP codes) are generally quite secure (since they aren’t transmitted over networks), but those are usually used as a second factor rather than primary login, so beyond our scope here.

OTP codes expire quickly and cannot be reused, limiting the window an attacker could use a stolen code. Overall, OTPs provide a strong security balance if implemented well, which is why security-sensitive platforms often prefer them. Just be mindful of delivery risks and use additional measures (e.g. rate limiting, fraud detection) to prevent OTP abuse.

Magic link security

Magic links essentially turn the user’s email into the authentication factor (“something you have”: access to the email account). Therefore, the security of magic links is only as strong as the security of the user’s email. If an attacker gains access to a user’s email inbox, they could click magic link emails and instantly compromise that user’s accounts.

This is an important consideration: while users tend to secure their primary email better than they do most passwords, email account takeover is still a prime target for attackers. Beyond that fundamental reliance, magic links have a few specific security considerations:

Email deliverability and interception: Magic link URLs must be delivered via email (or sometimes SMS). If those emails don’t reach the user (get caught in spam filters or delayed), users might request multiple links or give up, which could open the door to confusion or phishing.

Also, sending a login URL over email means it passes through various servers; using HTTPS links and expiring tokens mitigates the risk, but a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacker on an insecure network could theoretically snag the token from the URL if the link is clicked on a non-HTTPS page. Always ensure your magic link implementation uses SSL and one-time, short-lived tokens.

Phishing and social engineering: Magic link emails could be mimicked by phishers. Users might be tricked into clicking a fake “magic link” email that actually leads to a malicious site. In practice this risk is similar to any password reset email phishing.

The takeaway is that magic links should be implemented with proper security (SSL, anti-phishing measures) and ideally complemented by user education or secondary factors for sensitive accounts.

Automatic link activation: A unique risk with magic links is what happens after the email is sent. Corporate email systems or antivirus scanners sometimes auto-click links to check for threats. This can prematurely “use up” a magic link before the user clicks it. From a security standpoint, this doesn’t let an attacker in, but it does mean the legitimate user’s link is now invalid (creating a denial-of-service for that login attempt). OTP codes, by contrast, cannot be auto-used by a scanner.

Session hijacking concern: By design, a magic link lets someone who has that link log in. If a user forwards that email or an attacker somehow obtains the link, they could use it from another location.

Some implementations mitigate this by tying the link to the device that requested it (for instance, requiring the same browser session). OTPs are generally tied to a specific user but not device, so in principle a stolen OTP could also be used anywhere.

For higher-security scenarios, neither email OTP nor magic link alone is recommended; instead they should be combined with additional factors or replaced with more phishing-resistant methods.

In summary, OTPs are often seen as a safer choice for highly sensitive or high-risk accounts because they can act as a true second factor and have well-understood failure modes. Magic links offer reasonable security for many consumer applications (and they eliminate weak passwords), but they inherently trust the user’s email security.

If you implement magic links, enforce best practices: unique, hard-to-guess tokens, short expiration times, and possibly notify users on successful login so they’re aware if a link was used without their action.

For OTPs, choose reliable channels and consider limiting use to safer channels (email or authenticator app) in regions where SIM swap fraud is rampant. Both methods should be augmented with good security hygiene (monitoring for suspicious logins, offering users 2FA options, etc.) for optimal protection.

3. Implementation complexity

Another practical consideration is how complex each method is to implement and maintain, including the cost and infrastructure overhead.

Implementing OTP login

Setting up OTP-based authentication is straightforward, especially with many APIs and services available. If using SMS OTP, you’ll need an SMS gateway/provider service to send texts, and code to generate and verify the one-time codes.

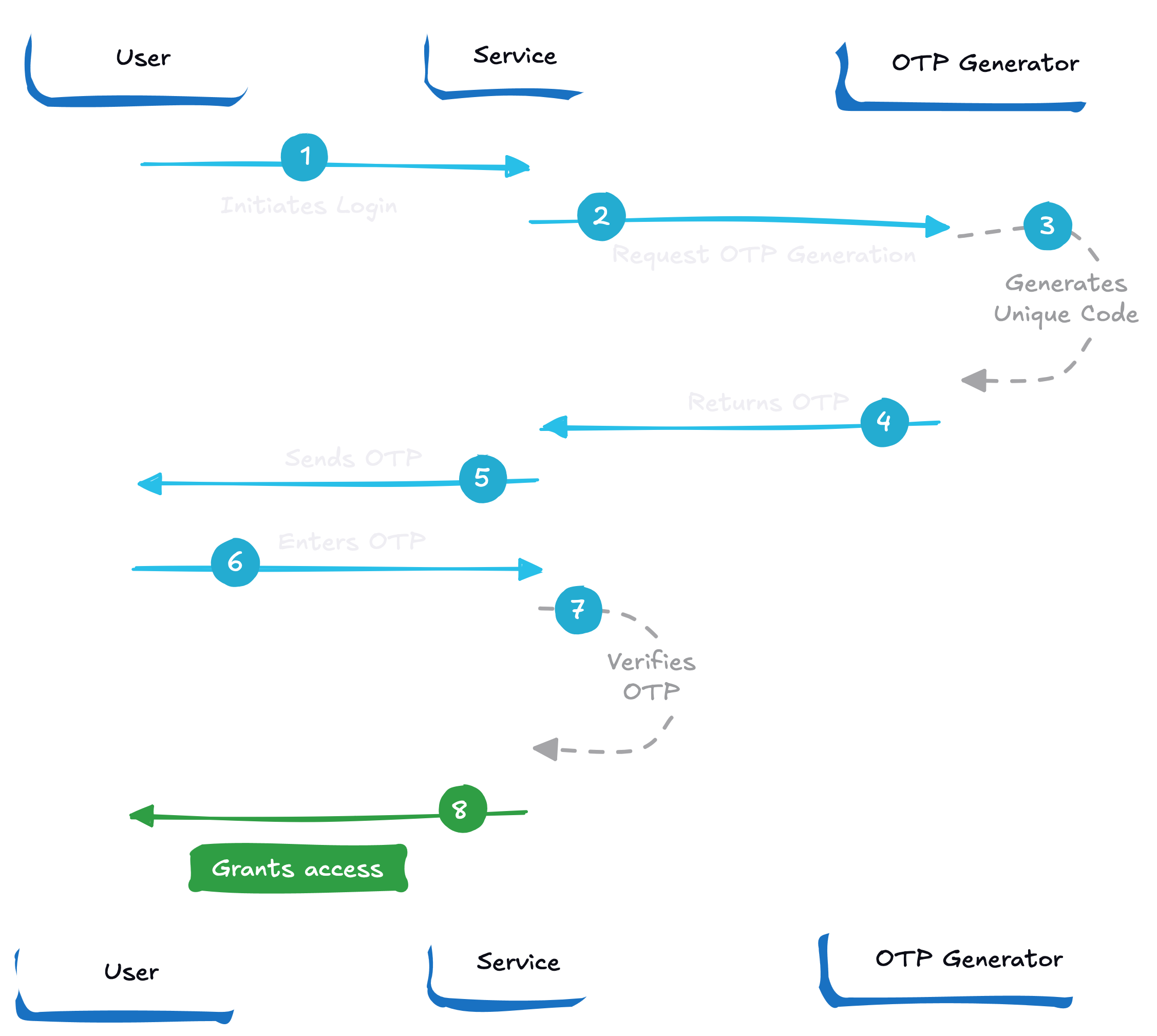

Here’s how OTP login works:

Many developers might find OTP integration easier because it’s a single short code to verify. The challenges come in the details: ensuring the codes expire and cannot be reused, preventing brute-force guessing, and handling delivery failures gracefully. If you expect to send large volumes of OTPs, cost can become a factor. Sending SMS is not free, and at scale those messages can quickly add up in cost.

Email-based OTPs are cheaper (just an email sent), but still require an email delivery service and can suffer delays or spam filtering. Also, you’ll need a user interface for inputting the code and a flow for resending codes upon request. Overall, OTP login is a well-trodden path; many libraries and providers support it out of the box, and most development teams can implement a basic OTP system without too much trouble.

Implementing magic links

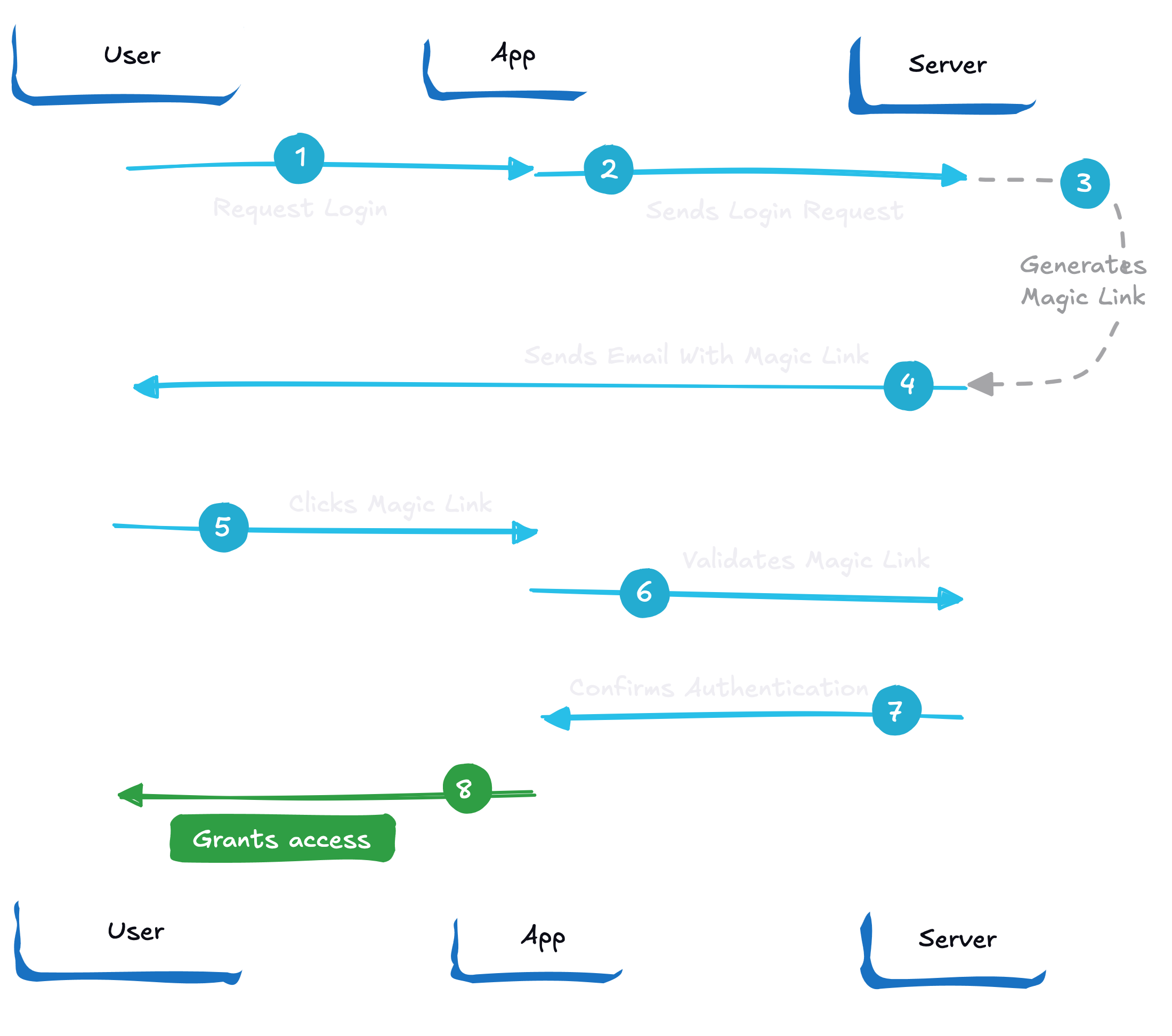

Magic links require generating a secure token, storing it or its hash temporarily on the backend, and sending the token to the user as a clickable link, usually via email. On the user’s click, your app must receive the request, often on a special endpoint or callback URL, verify the token, and then log the user in. Here’s how magic links work:

Here’s an example of how to implement Magic Links using Scalekit:

Sending a verification email using Scalekit

Verifying the user’s identity using Scalekit

It’s like a password reset flow that logs the user in instead of asking for a new password. The initial implementation of magic links can be comparably simple: many authentication platforms treat “email magic link” as just an alternative flow that can be enabled.

If building yourself, you’ll need to create that email template and ensure the link URL contains a unique token and perhaps some state info.

One extra complexity with magic links is deep linking for mobile apps. If your users log in on mobile devices, you’ll want the magic email link to open your app and sign the user in, rather than just opening a web browser.

Achieving this requires implementing universal links or custom URL schemes and handling them in your app, which adds development effort.

By contrast, an SMS OTP on mobile can be entered within the app directly, often aided by OS autofill. So, supporting magic links seamlessly across web and mobile might be a bit more engineering work than OTP in some cases.

4. Reliability and maintenance

Magic links depend on reliable email delivery. If your email service has issues or delays, or if the email lands in spam, users will be stuck waiting to log in.

You need to monitor deliverability and perhaps employ strategies like fallback to a different method if email fails.

OTP via SMS similarly depends on telecom reliability, and you might need to handle cases where SMS is delayed or blocked for some carriers. In both cases, having metrics and a fallback (like offering the user “resend code” or an alternate channel) improves reliability.

Magic link implementation also should consider the edge case of link misuse: For example, ensure a user can’t use the same link twice, handle expired links with a friendly retry flow, etc. OTP systems must guard against too many attempts or code guesses.

5. Administrative overhead and cost

SMS OTP incurs per-message costs, potentially significant for apps with huge user bases or frequent logins. Magic links send emails, which are generally cheaper (especially if you use your own email server or a reasonable email API service).

On the support side, OTP might generate queries like “I didn’t get my code” or “my code doesn’t work,” while magic link users might say “I didn’t receive the email” or “the link expired.” So whichever method, be prepared to handle some user support.

Decision framework

How do you choose between OTP and magic links for your passwordless authentication? The right choice depends on your user base, use case, and priorities. Both methods have their merits, so let’s break down some key factors and scenarios to guide the decision:

- User preference and familiarity: Consider what your users might be more comfortable with. Are they mainly mainstream consumers or enterprise users? If your audience might find an emailed link strange or miss it, OTP might be safer

- Security requirements: Evaluate the security level your platform needs. If you’re handling highly sensitive data (financial info, medical records, etc.), leaning toward OTP (or at least OTP as one factor in MFA) is advisable. Magic links are acceptable for moderate security needs but might not meet the bar for stringent environments or compliance regimes.

- Device and usage pattern: Think about where users will log in and how often. If your app is mobile-first or primarily identifies users by phone number, OTP (SMS) is almost a no-brainer. If your users log in infrequently (say, once in a while to a SaaS tool) and primarily via desktop web, magic links offer a very convenient, low-effort login each time.

- Conversely, if users log in daily or multiple times a day, magic links could become annoying (constant emails) and OTP might be a bit better, though ideally a persistent session or another solution would be used in that case.

- Infrastructure and cost: If you have reliable email infrastructure and want to avoid SMS costs, magic links might be appealing. If SMS cost or deliverability is a concern (for global user bases, SMS can indeed be costly and sometimes unreliable), an email magic link keeps everything over the internet.

- Also, consider development resources: implementing SMS OTP involves dealing with third-party SMS APIs and phone number verification; implementing magic links involves robust email delivery and handling link clicks. Choose the one your team can execute best.

Common scenarios and recommendations

- Banking/Fintech or other high-security apps: OTP recommended. These often use OTP as a second factor anyway. It provides a proven level of security and aligns with user expectations for secure login. Magic links alone would likely not satisfy security requirements here.

- Mobile-first social or utility app (using phone number sign-up): OTP (SMS) strongly preferred. Users in this case sign up with a phone number, so sending a code via SMS is a natural verification step. It’s quick and doesn’t force an email step. Magic link would require collecting an email which adds friction for a user who just gave a phone number.

- Web-based SaaS with infrequent login (e.g., periodic use): Magic Link shines. For a SaaS where users log in maybe once a week or a few times a month, a magic link sent to email is low-friction. Users likely have their email open and can log in with one click. It also spares them from managing yet another password for a service they use occasionally. (If the SaaS contains sensitive data, you might combine magic link with an OTP for MFA on critical actions, as a hybrid approach.)

- Consumer e-commerce platform or app: Either can work, but magic links could help reduce barriers at checkout. For example, if users are prompted to log in or sign up during checkout, a magic link can get them signed in quickly without disrupting the purchase flow. OTP would also remove password friction, though asking for a code might feel a bit more involved than clicking a link.

- Enterprise SaaS with domain-based users: Lean towards OTP or SSO. Enterprise users often have Single Sign-On (SSO) via their company, but if not, OTP is usually better since many corporate email systems aggressively scan or modify incoming emails, potentially breaking magic links. Magic links might be seen as less secure in that context (and some enterprise users might not trust a random link in an email).

In conclusion, weigh your primary use case: If usability and minimal friction are top priority and you’re targeting a web-savvy or consumer audience, magic links are very appealing.

If security, reliability, or a mobile-first experience take priority, OTP might be the better fit. Both methods enhance user experience by removing passwords.

It’s about choosing the one that best aligns with your users’ needs and your app’s context. Consider conducting a pilot with each method and gather feedback. Whichever you choose, you’ll be joining many organizations in moving towards a passwordless future.

FAQs

How should architects choose between OTP and magic link methods?

When selecting between OTP and magic links, architects must balance user friction against security requirements. OTP is ideal for high security environments like fintech because it provides a proven second factor and handles delivery failures through familiar patterns. Magic links offer a seamless, one click experience for infrequent SaaS users but rely heavily on the security of the underlying email infrastructure. For enterprise applications, OTP is often more reliable because corporate mail scanners can inadvertently trigger and invalidate magic link tokens before the intended user can click them.

What are the primary implementation challenges for mobile magic links?

Implementing magic links for mobile applications requires sophisticated handling of universal links or custom URL schemes to ensure a seamless transition from the email client to the app. Without proper deep linking, users might be redirected to a mobile browser session instead of the authenticated application state. Conversely, SMS based OTP is often easier to implement on mobile devices because modern operating systems can automatically detect and surface the code for one tap entry. This eliminates the need for complex browser to app handoffs while maintaining a high level of security and user convenience.

Why do corporate email security filters frequently break magic links?

Many enterprise environments employ automated antivirus scanners and link protection services that proactively visit URLs in incoming emails to check for malicious content. This automated activation can prematurely consume the one time token associated with a magic link, rendering it invalid by the time the actual employee attempts to log in. To mitigate this, architects should consider using OTP or requiring a deliberate secondary action on the landing page to confirm the login. This ensures that automated security probes do not result in a denial of service experience for legitimate enterprise users.

How do SMS and email authentication costs scale for B2B?

Cost is a significant factor when scaling authentication for large user bases. SMS based OTP incurs per message charges from telecom providers, which can become substantial as login frequency increases or as you expand into international markets with varying carrier rates. In contrast, magic links and email based OTPs are generally much more cost effective since they leverage standard email delivery APIs. For B2B platforms with high frequency login patterns, moving toward email based methods or persistent sessions can significantly reduce operational overhead while maintaining the security benefits of a passwordless architecture.

What are the security risks associated with SMS based OTP delivery?

While SMS OTP is widely used, it is susceptible to telecom level vulnerabilities like SIM swapping and interception. Attackers can hijack a user phone number to receive their authentication codes, bypassing the security of the passwordless flow. To address these risks, CISOs often prefer authenticator apps or email based methods for sensitive transactions. When implementing SMS OTP through providers like Scalekit, it is critical to use fraud detection and rate limiting to monitor for suspicious activity. For the highest security tier, combining these methods with hardware keys or biometric factors is recommended.

Can magic links be utilized for AI agent authentication flows?

Magic links are generally unsuitable for AI agents or machine to machine authentication because they require a human to interact with an email client. For AI agents or automated MCP servers, architects should focus on more programmatic methods like Dynamic Client Registration or short lived M2M tokens. While magic links excel at reducing friction for human users in a browser, automated systems require non interactive methods to establish identity. Using a centralized auth provider allows you to manage these diverse identities, both human and agentic, under a unified security policy while providing appropriate authentication mechanisms.

How should architects manage session state during passwordless authentication?

Maintaining state during the transition from a login request to verification is crucial for a consistent user experience. When a user requests an OTP or magic link, the backend must securely store the associated state or return it to the client to prevent session hijacking. Scalekit simplifies this by including state parameters in the verification call, ensuring the user returns to the correct context after clicking a link or entering a code. This architecture prevents inconsistencies where a user might initiate a login on one device but accidentally complete it in a different browser session.

How do passwordless methods improve overall organizational security posture?

Passwordless authentication significantly reduces the risk of credential based attacks by eliminating static passwords, which are frequently reused across multiple services. By shifting to OTP or magic links, organizations ensure that a database breach at one provider does not compromise their users accounts elsewhere. This architecture effectively mitigates the impact of phishing, as there are no long lived secrets for an attacker to harvest. For engineering managers, this reduces the burden of managing complex password policies and the support costs associated with password resets, allowing the team to focus on core product features.

Should B2B applications implement multiple passwordless authentication fallbacks?

Yes, providing fallback options is a best practice for ensuring high availability in authentication. Email delivery issues or telecom delays can prevent a user from receiving their primary login factor. A robust architecture might offer a magic link as the primary method but allow the user to request an OTP via an alternate channel if the link fails. This multi channel approach improves reliability and reduces user frustration. By using a flexible auth provider, teams can easily configure these flows to balance user experience with the specific security needs of their B2B enterprise clients.